Lineage Switching: How lung cancer cells change identity

Cancer cells that arise from different areas of the body will share several common hallmarks (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). However, it is possible to distinguish between these cells as they will also retain features of their tissue of origin. This lineage is important because it helps determine which cancer treatments will be the most effective and whether the genes responsible for making the cell cancerous can be targeted with a specific therapy.

However, some cancer cells can also switch lineage, allowing them to evade treatments tailored to these specific ‘oncogenes’ (Quintanal-Villalonga et al., 2020). Reminiscent of the differentiation process that takes place for stem cells during embryonic development, this ability to transition from one lineage to another could be genetically or epigenetically encoded and may represent a hallmark of cancer (Le Magnen et al., 2018).

A clinically important example of lineage switching is seen in a type of lung cancer known as adenocarcinomas (or LUADs). Some of these tumors have mutations in the genes coding for either the EGFR or KRAS proteins, which overactivate the MAPK signaling pathway – a molecular cascade which normally helps cells to respond appropriately to their environment by controlling cell division and other biological processes.

LUADs with mutations in the gene for EGFR can be treated with a therapy that specifically targets this oncogene. However, after treatment about 5% of these LUADs will adopt another lineage, turning instead into an aggressive neuroendocrine tumor called small cell lung cancer (SCLC; Offin et al., 2019; Aggarwal et al., 2018). Neuroendocrine cancer can also emerge at other sites in the body, such as the prostate following treatment with another targeted therapy. Regardless of their origin, all advanced neuroendocrine tumors share similar molecular features, are difficult to treat and can spread quickly (Park et al., 2018). They also do not respond to the EGFR-targeted drugs used to treat LUADs, as they rarely express the mutated proteins, even if the mutations are present in the genome. Conversely, SCLCs that become resistant to standard chemotherapy may lose expression of neuroendocrine features and transition to another lineage. Although recent studies have shed light on how lineage switching happens at the molecular level (Marjanovic et al., 2020; Ku et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019), there are still crucial gaps in our knowledge about the biological mechanisms underlying these transitions.

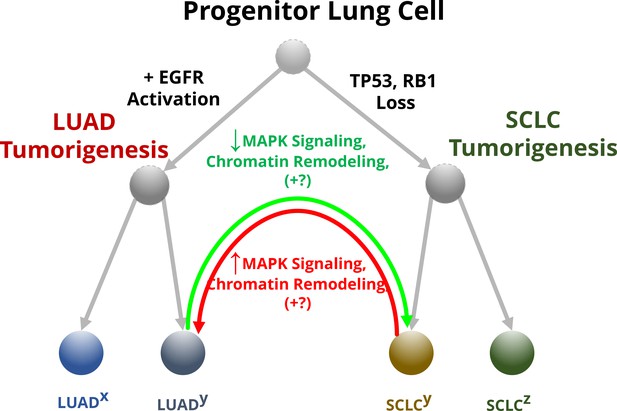

Now, in eLife, William Lockwood from the British Columbia Cancer Agency and co-workers in Canada and the United States – including Yusuke Inoue as first author – report that the MAPK signaling pathway may regulate lineage switching in lung cancer cells (Inoue et al., 2021). First, experiments revealed that activating MAPK signaling, by increasing the levels of EGFR and KRAS, caused SCLC cells from patients to express fewer neuroendocrine markers when cultured in the laboratory. In particular, MAPK signaling reduced the expression of transcription factors needed for neuroendocrine cell traits. This suggests that the high levels of MAPK activation normally found in LUADs usually prevents these cancer cells from adopting a neuroendocrine identity (Figure 1). Furthermore, these molecular changes impacted how the tumor cells grew and behaved, suggesting that these transformed SCLC cells can be used as a preclinical model for studying aspects of lineage switching.

The effect of MAPK signaling on lineage switching in lung cancer cells.

Progenitor lung cells are able to develop into different types of cancer. Cells with high levels of EGFR and other proteins involved in the MAPK pathway are more likely to transition in to lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs; left), while mutations that impair the tumor suppressor genes TP53 and RB1 lead to the formation of neuroendocrine tumors called small cell lung cancers (SCLCs; right). Some of these cells (annotated with a superscript ‘y’) will undergo further molecular changes that will allow them to transition between these two lineages, while others (annotated with superscripts ‘x’ and ‘z’) will be unable to change their identity. For example, LUADs with mutations that impair the activity of TP53 and RB1 can switch to a SCLC phenotype (green arrow). Inoue et al. found that this conversion depends on the reduced activity of the MAPK signaling pathway, plus additional unknown factors (indicated with +?): this alters the structure of chromatin so that the transcription machinery of the cell can access and switch on the genes for transcription factors that specify the neuroendocrine identity. Some SCLC cells can also transition into LUADs (red arrow) by reactivating the MAPK signaling pathway, which leads to chromatin remodeling that limits access to the genes for the neuroendocrine transcription factors.

Further experiments showed that the terminal component of the MAPK pathway, known as ERK, is responsible for changing the expression of transcription factors which specify neuroendocrine identity. Inoue et al. found that ERK activates two proteins (CBP and p300) that alter the conformation of the DNA segments in which the genes for the neuroendocrine transcription factors reside, stopping them from being transcribed. When ERK and CBP/p300 were inhibited, increasing the levels of EGFR and KRAS no longer reduced the expression of neuroendocrine transcription factors. This provides strong evidence that these three proteins (ERK, CBP and p300) all play a key role in controlling neuroendocrine identity.

Next, Inoue et al. attempted to recapitulate the lineage transition seen in patients, where LUADs occasionally switch to a neuroendocrine SCLC phenotype. To do this, they first genetically engineered LUAD cells with existing mutations in the gene for EGFR and the tumor suppressor gene TP53 to have an additional molecular change which reduces the activity of another tumor suppressor gene called RB1: these genetic alterations are found in nearly all LUADs that assume a neuroendocrine phenotype as a resistance mechanism to EGFR-targeted therapy. These cells were then exposed to a potent EGFR inhibitor. However, despite the cells becoming resistant to the inhibitor treatment, no change in growth characteristics, lineage markers or switch to a neuroendocrine phenotype were identified.

It is unclear why this strategy did not work, and what additional steps are needed for LUADs to fully transition into neuroendocrine cells. This process may be more successful in vivo, or other molecular differences between SCLCs and LUADs could play a role. Nevertheless, these carefully conducted ‘negative’ studies commendably illustrate that important details are missing about this transition, which is involved in a range of human cancers and is associated with poor prognosis (Balanis et al., 2019).

Finally, the molecular insights gained from Inoue et al. could be expanded on and used in the clinic to both test and develop new therapies. This could help identify which patients are most at risk of tumor lineage switches and enable early interventions that improve the outcomes of treatment.

References

-

Generation of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and SCLC-like tumors from human embryonic stem cellsJournal of Experimental Medicine 216:674–687.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20181155

-

Lineage plasticity in cancer progression and treatmentAnnual Review of Cancer Biology 2:271–289.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030617-050224

-

Lineage plasticity in cancer: A shared pathway of therapeutic resistanceNature Reviews. Clinical Oncology 17:360–371.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0340-z

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2021, von Itzstein et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,787

- views

-

- 173

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 5

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.71610