Risk Modeling: Predicting cancer risk based on family history

Countless hours have been dedicated to researching cancer – how to prevent it, how to diagnose it early, and how to treat it. Yet, cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for almost 10 million fatalities in 2020.

Most cancers are caused by changes to genes that happen over a person’s lifetime. In rarer cases (about 5–10%), they start due to inherited genetic mutations that produce a predisposition to cancer. In these instances, also known as familial or hereditary cancer syndromes, the mutation is passed down from generation to generation. In these families, more members tend to develop cancers than expected – often of the same or related type – which can also start at a particularly early age.

It is important to identify people with such genetic mutations so that they – and any family members at higher risk – can undergo enhanced cancer screening. Family history can be a useful predictor of hereditary cancer risk (Blackford and Parmigiani, 2010). As such, risk prediction models that incorporate family history to estimate a person’s chance of having a mutation in a cancer predisposition gene or of developing cancer have been employed for many years (Chen et al., 2004).

Historically, such models have been particularly valuable for deciding who to offer genetic testing to when only few and often costly genetic tests were available (Fasching et al., 2007). In some cases, insurance companies require the risk estimate related to carrying a cancer-related genetic mutation to exceed a certain threshold (typically 5 or 10%) to reimburse the cost of a genetic test (Chen et al., 2006). As research advances, the number of genes available for cancer-related genetic testing has now reached over 100 and is likely to continue increasing. Nevertheless, older risk modeling programs generally include only a small number of genes in their predictions. Now, in eLife, Danielle Braun and colleagues – including Gavin Lee and Jane Liang as joint first authors – report on a new software package that has the capacity to evolve alongside advances in cancer research (Lee et al., 2021).

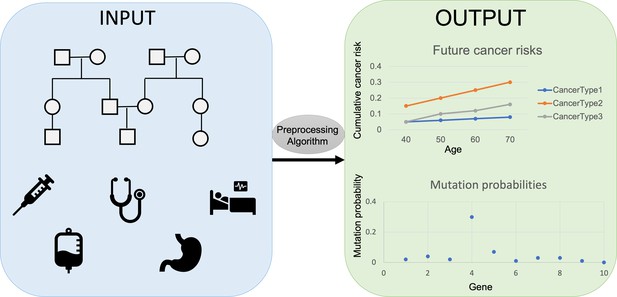

The researchers, who are based at ETH Zürich, EPFL, Harvard, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and the Broad Institute, developed PanelPRO, a tool that uses evidence gathered from extensive literature reviews to model the complex interplay between genes and cancer risk. PanelPRO’s workflow consists of four main parts: input, preprocessing, algorithm, and output (Figure 1).

Workflow for PanelPRO.

First, information on family history, including cancer diagnoses, age of relatives, and cancer risk factors is added into the risk modeling software PanelPRO (input, blue box on the left). Then, PanelPRO validates data formatting (preprocessing, grey oval), and analyses information about frequency and cancer risks for family cancer syndromes (algorithm, grey box) to estimate the likelihood of a person in a family having a mutation in a gene linked to an increased risk of cancer (output, green box on the right). Mutation probability and cumulative cancer risk are given as a probability between 0.0 (no risk) and 1.0 (100% risk).

The user first adds information about a history of cancers in a family – such as ages and cancer diagnoses – and other factors that might affect cancer risk. These include any risk-reducing surgeries in relatives, or tumors with biomarkers that might indicate a potential hereditary cause of their cancer. The software then adds information on the frequency of different hereditary cancer syndromes and assesses their associated cancer risks. PanelPRO can currently accommodate 18 types of cancer and generate predictions of probable mutations for 24 genes, but its code allows for the addition of new cancers or cancer-related genes that may be identified in the future.

During the preprocessing stage, the software verifies the input for any missing information and data, and also for any family relationships not supported by the software, such as ‘double cousins’, which occur when two siblings have children with two siblings from another family. Messages, warnings, or errors may be given to the user if any issues are detected.

After the information has been checked and modified as needed, the model proceeds to the algorithm stage. To calculate the output, the algorithm uses probabilities based on the family history, the frequency of hereditary cancer syndromes in the population, and the cancer history that would be expected if a cancer syndrome were present. The program then estimates the likelihood of a person in a family to have a mutation in a gene linked to an increased risk of cancer. These calculations can also be easily run for other family members using the existing information. It also shows a personalized estimate of future cancer risks. Users can choose which cancer types and genes to display.

However, some outstanding issues remain. Misreported family history information, such as an inaccurate cancer diagnosis or unknown age of diagnosis, can significantly affect estimates, highlighting that accuracy of patient-reported information is key to producing correct estimates (Katki, 2006). While patients have been shown to generally provide exact information on cancer history for first-degree relatives, the accuracy of these reports decreases for more distant relations (Augustinsson et al., 2018; Murff et al., 2004).

Moreover, analyses with a similar risk modeling software have revealed that a strict adherence to a 10% risk threshold to qualify for a test for a probable mutation in the BRCA gene (which is linked to an increased risk of developing breast, ovarian, and other cancers) would miss around 25% of individuals carrying a mutation when compared to genetic testing outcomes (Varesco et al., 2013). This is likely because cancer risks associated with hereditary cancer syndromes are more variable than initially appreciated, and not all family histories may exhibit a predictable pattern of cancer, even when a mutation is present (Okur and Chung, 2017). This complicates risk assessments and argues against making decisions about genetic testing solely based on risk prediction models. Today, broader insurance coverage guidelines and lower costs for genetic tests have increased clinicians’ ability to order these tests, even if certain risk thresholds are not met based on family history.

Nevertheless, the higher number of genes and cancer types supported by PanelPRO compared to other risk models are impressive and its ability to incorporate new genes and cancer types as testing advances are key in this fast-paced, constantly advancing field.

References

-

BookFamilial cancer risk assessment using BayesMendelIn: Michael F. O, John T. C, editors. Biomedical Informatics for Cancer Research. Springer. pp. 301–314.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5714-6

-

BayesMendel: an R environment for Mendelian risk predictionStatistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology 3:1–19.https://doi.org/10.2202/1544-6115.1063

-

Evaluation of mathematical models for breast cancer risk assessment in routine clinical useEuropean Journal of Cancer Prevention 16:216–224.https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32801023b3

-

The impact of hereditary cancer gene panels on clinical care and lessons learnedMolecular Case Studies 3:a002154.https://doi.org/10.1101/mcs.a002154

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: September 29, 2021 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2021, Jacobs

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 918

- views

-

- 53

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Collective cell migration is fundamental for the development of organisms and in the adult for tissue regeneration and in pathological conditions such as cancer. Migration as a coherent group requires the maintenance of cell–cell interactions, while contact inhibition of locomotion (CIL), a local repulsive force, can propel the group forward. Here we show that the cell–cell interaction molecule, N-cadherin, regulates both adhesion and repulsion processes during Schwann cell (SC) collective migration, which is required for peripheral nerve regeneration. However, distinct from its role in cell–cell adhesion, the repulsion process is independent of N-cadherin trans-homodimerisation and the associated adherens junction complex. Rather, the extracellular domain of N-cadherin is required to present the repulsive Slit2/Slit3 signal at the cell surface. Inhibiting Slit2/Slit3 signalling inhibits CIL and subsequently collective SC migration, resulting in adherent, nonmigratory cell clusters. Moreover, analysis of ex vivo explants from mice following sciatic nerve injury showed that inhibition of Slit2 decreased SC collective migration and increased clustering of SCs within the nerve bridge. These findings provide insight into how opposing signals can mediate collective cell migration and how CIL pathways are promising targets for inhibiting pathological cell migration.

-

- Cancer Biology

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) directed against MET have been recently approved to treat advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harbouring activating MET mutations. This success is the consequence of a long characterization of MET mutations in cancers, which we propose to outline in this review. MET, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), displays in a broad panel of cancers many deregulations liable to promote tumour progression. The first MET mutation was discovered in 1997, in hereditary papillary renal cancer (HPRC), providing the first direct link between MET mutations and cancer development. As in other RTKs, these mutations are located in the kinase domain, leading in most cases to ligand-independent MET activation. In 2014, novel MET mutations were identified in several advanced cancers, including lung cancers. These mutations alter splice sites of exon 14, causing in-frame exon 14 skipping and deletion of a regulatory domain. Because these mutations are not located in the kinase domain, they are original and their mode of action has yet to be fully elucidated. Less than five years after the discovery of such mutations, the efficacy of a MET TKI was evidenced in NSCLC patients displaying MET exon 14 skipping. Yet its use led to a resistance mechanism involving acquisition of novel and already characterized MET mutations. Furthermore, novel somatic MET mutations are constantly being discovered. The challenge is no longer to identify them but to characterize them in order to predict their transforming activity and their sensitivity or resistance to MET TKIs, in order to adapt treatment.