Role of oxidation of excitation-contraction coupling machinery in age-dependent loss of muscle function in Caenorhabditis elegans

Figures

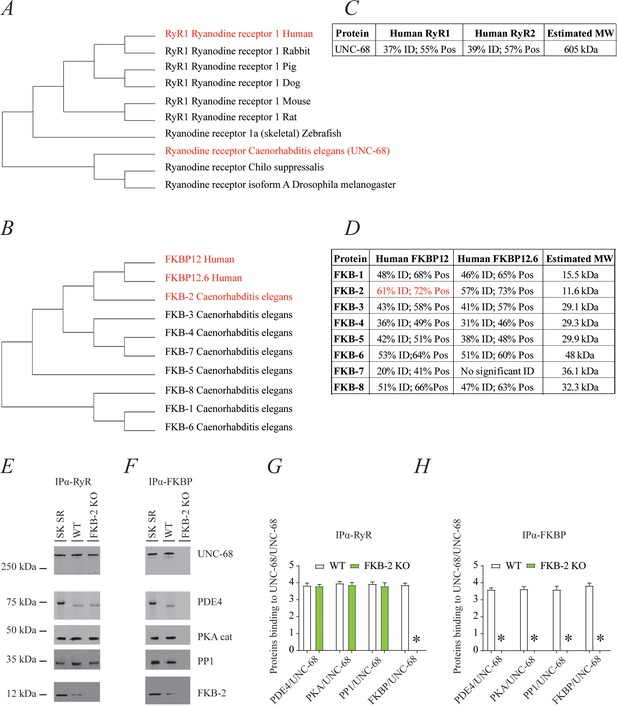

UNC-68 comprises a macromolecular complex comparable to its mammalian homolog ryanodine receptor (RyR); RyR (A) and FKBP (B) evolution among species was inferred by the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model.

(C) Homology comparison between UNC-68 and the two human RyR isoforms (RyR1 and RyR2). (D) Homology comparison between the different FKB isoforms (1–8) and the human FKBP isoforms (FKBP12 and FKB12.6). UNC-68 (E) and FKB-2 (F), respectively, were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted using anti-RyR, anti-phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), anti-protein kinase A (catalytic subunit; PKAcat), anti-protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), and anti-calstabin (FKBP) antibodies in murine skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum preparations (SK SR), wild-type (WT) populations of Caenorhabditis elegans, and populations of FKB-2 (ok3007). Images show representative immunoblots from triplicate experiments. (G and H) Quantification of bands intensity shown in E and F. Data are means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA shows * p<0.05 WT vs. FKB-2 KO. SK SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum fraction from mouse skeletal muscle. Figure 1—source data 1.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Full incut gels of Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-fig1-data1-v2.pdf

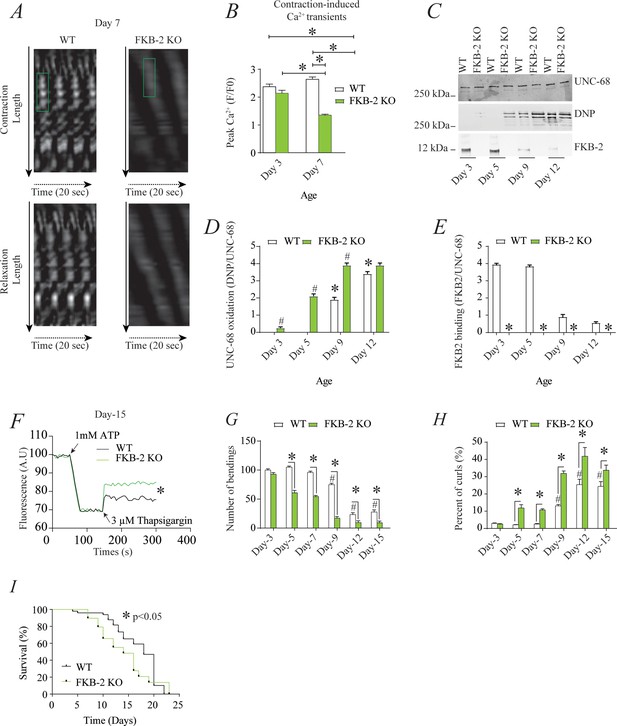

Remodeling of UNC-68 and age-dependent reduction in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) transients is accelerated in FKB-2 (ok3007) (A) Representative trace of Ca2+ transients from GCaMP2 wild type (WT) and FKB-2 KO (at day 7).

Green box denotes peak fluorescence from worm’s muscle during contraction. (B) Ca2+ transients in age-synchronized populations of WT and FKB-2 (ok3007) nematodes (at day 3 and 7); (C) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated from age-synchronized populations of mutant (FKB-2 KO) and WT nematodes (at day 3, 5, 9, and 12) and immunoblotted using anti-RyR, anti-calstabin, and dinitrophenyl (DNP; marker of oxidation) antibodies. (D and E) Quantification of the average band intensity from triplicate experiments: band intensity was defined as the ratio of each complex member’s expression over its corresponding /UNC-68’s expression. Data are means ± SEM. * p<0.05 WT vs. FKB-2 KO in panel D, # p<0.05 WT vs. FKB-2 KO in panel E, * p<0.05 WT at day 3 vs. WT at day 5 and day 9. (F) Ca2+ leak assay performed with microsomes from WT and FKB-2 KO worms (day 5). Ca2+ uptake into the microsomes was initiated by adding 1 mM of ATP. Then, 3 µM of thapsigargin was added to block the sarco/endoplasmic calcium ATPase activity. Increased fluorescence is proportional to the spontaneous Ca2+ leakage throughout UNC-68. (G) Graph showing number of bends recorded for WT vs. FKB-2 KO worms at six distinct ages (day 3, 5, 7, 9, 12, and 15). (H) The number of curling events was calculated as a percentage of the overall motility (curls/bends). N = ~60 worms per group, except for day 15 (as fewer worms were alive at this timepoint). Day 15 = ~40 worms. (I) Percentage of survival of WT (average survival; 18 days) and FKB-2 KO worms (average survival; 14 days); Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test for survival comparison was performed for statistical significance. Data are means ± SEM from triplicate experiments. One-way ANOVA shows * p<0.05 WT vs. FKB-2 KO, # p<0.05 WT at day 3 vs. WT at day 5, 7, 9, 12, and 15. Figure 2—source data 1.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Full incut gels of Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-fig2-data1-v2.pdf

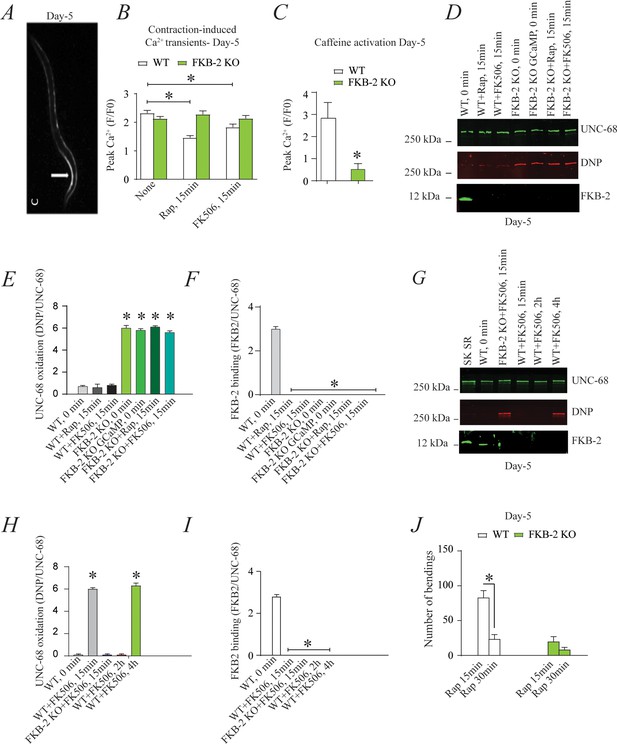

Depleting FKB-2 from UNC-68 causes UNC-68 oxidation (A) Representative image of caffeine activated calcium transient in GCaMP2 wild type (WT) at day 5; arrow denotes peak fluorescence in body wall muscle.

(B) Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) transients in day 5 age-synchronized populations of WT and FKB-2 (ok3007) nematodes treated with 15 μM and 50 μM rapamycin and FK506, respectively (treatment was applied for 15 min). (C) Fluorescence intensity following caffeine activation in age-matched GCaMP2: WT vs. GCaMP2: FKB-2 KO worms at day 5. (D) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted using anti-ryanodine receptor, anti-calstabin, and dinitrophenyl (DNP; marker of oxidation) antibodies in nematodes (at day 5) acutely treated with 15 μM and 50 μM rapamycin and FK506, respectively (treatment was applied for 15 min). (E–F) Quantification of the band intensity shown in (D): band intensity was defined as the ratio of either DNP (marker of UNC-68 oxidation) or FKB-2 binding over its corresponding /UNC-68’s expression. (G) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated after 0, 15 min, 2 hr, and 4 hr FK506 exposure of the nematodes (at day 5). Representative immunoblots from triplicate experiments. (H–I) Quantification of the band intensity shown in (G): band intensity was defined as the ratio of either DNP (marker of UNC-68 oxidation) or FKB-2 binding over its corresponding /UNC-68’s expression. (J) Graph showing number of bends recorded for WT vs. FKB-2 KO worms (Day 5) treated for 20 and 30 min with 15 μM and 50 μM rapamycin and FK506, respectively. N ≥ 15 per group. Data are means ± SEM from triplicate experiments. One-way ANOVA shows * p<0.05 vs. WT for results shown in panel E, F, H, and I. Two-way ANOVA was used for results comparison in panel B, and t-test was used for results shown in C and J. SK SR; sarcoplasmic reticulum fraction from mouse skeletal muscle used as external control reference and was not quantified in the bar graphs. The time 0 min refers to untreated worms. Figure 3—source data 1.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Full incut gels of Figure 3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-fig3-data1-v2.pdf

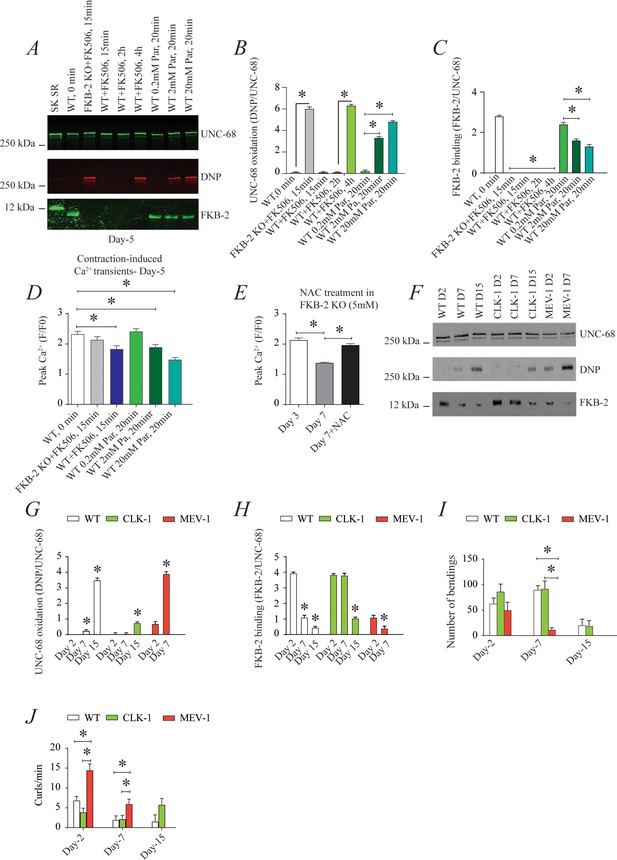

UNC-68 oxidation causes defective intracellular calcium (Ca2+) handling; (A) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted using anti-ryanodine receptor (RyR), anti-calstabin, and dinitrophenyl (DNP; marker of oxidation) antibodies in nematodes acutely treated for 0, 15 min, 2 hr, or 4 hr with FK506 or paraquat (treatment was applied for 20 min) at increasing concentration (day 5).

(B–C) Quantification of the band intensity shown in (A): band intensity was defined as the ratio of either DNP (marker of UNC-68 oxidation) or FKB-2 binding over its corresponding /UNC-68’s expression. (D) Contraction-associated Ca2+ transients measured in young age-synchronized WT nematodes treated for 15 with FK506 or for 20 min with increasing concentrations of paraquat (day 5). (E) Contraction-associated Ca2+ transients measured in FKB-2 KO nematodes treated with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) at 5 mM (day 7). (F) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted using anti-RyR, anti-calstabin, and DNP (marker of oxidation) antibodies in WT, the long lived (CLK-1) and the short lived (MEV-1) nematodes at day 2, 7, and 15. (G–H) Quantification of the average band intensity from triplicate experiments: band intensity was defined as the ratio of each complex member’s expression over its corresponding /UNC-68’s expression. (I) Graph showing number of bends recorded for WT vs. CLK-1 and MEV-1 worms at three distinct ages (day 2, 7, and 15). (J) The number of curling events was calculated as a percentage of the overall motility (curls/bends). N ≥ 20 per group. Data are means ± SEM from triplicate experiments. One-way ANOVA shows * p<0.05. Two-way ANOVA was used in panel I and J. SK SR; sarcoplasmic reticulum fraction from mouse skeletal muscle used as external control reference and was not quantified in the bar graphs. The time 0 min refers to untreated worms. Figure 4—source data 1.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Full incut gels of Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-fig4-data1-v2.pdf

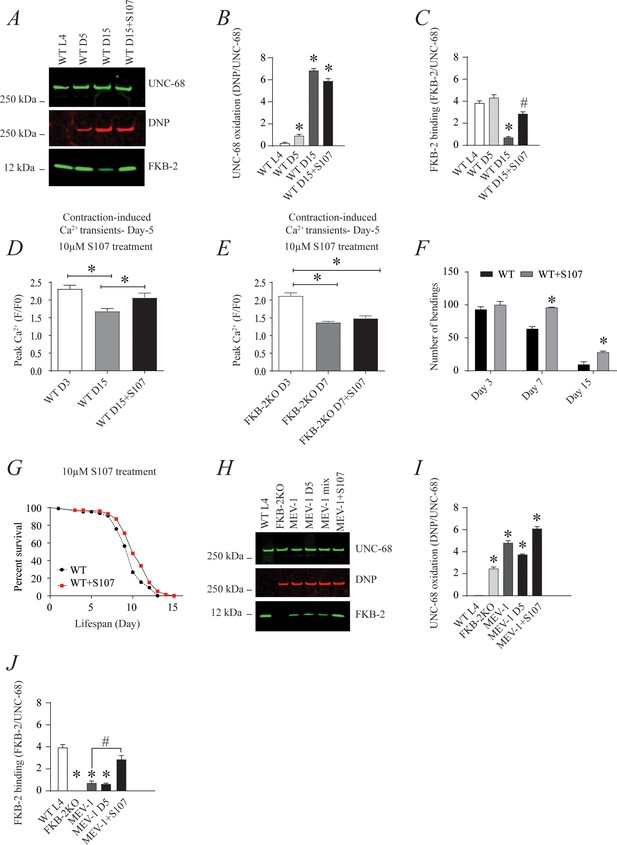

The ryanodine receptor (RyR)-stabilizing drug S107 increases body wall muscle calcium (Ca2+) transients in aged Caenorhabditis elegans; (A) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-RyR, anti-calstabin, and dinitrophenyl (DNP; marker of oxidation) in aged nematodes (Day L4, 5, and 15) with 10 µM of S107 (5 hr).

(B–C) Quantification of the band intensity shown in (A): band intensity was defined as the ratio of either DNP (marker of UNC-68 oxidation) or FKB-2 binding over its corresponding /UNC-68 expression. Data are mean ± SEM. * p<0.05 vs. wild-typd L4 (WTL4), # p<0.05 WT D15 vs. WT D15 + S107. (D–E) Contraction-associated Ca2+ transients were measured in age-synchronized WT (day 3 and 15) (D) and (E) FKB-2 KO worms (day 3 and 7). Contraction-associated Ca2+ transients in S107-treated worms were performed at day 15 for WT and day 7 for FKB-2 worms. (F) Graph showing number of bends recorded for WT vs. WT treated with S107 worms at different ages (day 3, 7, and 15). (G) Percent of survival of WT vs. WT treated with S107 nematodes; Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test for survival comparison was performed for statistical significance. (H) UNC-68 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-RyR, anti-calstabin, and DNP (marker of oxidation) in short-lived nematodes (MEV-1) with S107 treatment (5 hr). (I–J) Quantification of the band intensity shown in (H): band intensity was defined as the ratio of either DNP (marker of UNC-68 oxidation) or FKB-2 binding over its corresponding /UNC-68 expression. N ≥ 20 per group. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicate experiments. One-way ANOVA shows * p < 0.05 vs WT L4 unless otherwise indicated. In panel F, a t-test was used to compare WT and WT + S107 for each day. #p<0.05 MEV-1, vs. MEV-1 +S107 in panel J. Figure 5—source data 1.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Full incut gels of Figure 5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-fig5-data1-v2.pdf

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain, strain background (worms) | ok3007 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota) | WormBase ID: WBVar00094093 | Genomic position: I: 2918075.12918967 |

| Strain, strain background (worms) | Pmyo-3:GCaMP2 worms | Kindly provided by Zhao-Wen Wang, University of Connecticut Health Center | ||

| Strain, strain background (worms) | mev-1 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota) | WormBase ID: WBGene00003225 | Genomic position III: 10334277.10335168 |

| Strain, strain background (worms) | clk-1 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota) | WormBase ID: WBGene00000536 | Genomic position III: 5277894.5279344 |

| Antibody | anti-RyR1 (Rabbit polyclonal) | Marks’ lab, Columbia University, NY, USA | Cat. #: 5,029 Aa 1327–1339 | WB (1:1000), (10 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-PDE4 (Rabbit monoclonal) | Kindly provided by Kenneth Miller, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma | WB (1:1000), (10 μl) | |

| Antibody | anti-PP1 (Rabbit polyclonal) | Santa Cruz | Cat. #: sc6104 | WB (1:1000), (10 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-FKBP12 (Mouse monoclonal) | Santa Cruz | Cat. #: sc6104 | WB (1:2500), (10 μl) |

| Antibody | anti-FKBP12 (Rabbit polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat. #: ab2918 | WB (1:2000), (10 μl) |

| Commercial assay or kit | Oxyblot protein oxydation detection kit | Millipore | Cat. #: S7150 | WB (1:1000), (10 μl) |

| Chemical compound, drug | Rapamacin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. #: 37,094 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | FK506 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. #: Y0001926 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Paraquat | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. #: 36,541 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | S107rycal drug | Marks’ lab, Columbia University, NY, USA | ||

| Software, algorithm | GraphPad | GraphPad | V8.0 |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Oxidative regulators in C. elegans vs mice vs humans.

Comparison of homologous oxidative and antioxidative genes between C. elegans, mouse and human. Criteria of comparison includes the function, the subcellular location, the enzymatic activity, mutation induces disrupted phenotype and percentage of homology.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-supp1-v2.docx

-

Supplementary file 2

Amino acid composition of UNC-68 and Human RyR1.

Comparison of amino acid abundance in the C. elegans UNC-68 and the human RyR1 calcium channels. Number and percentage of Serines and methionines for each species are shown in red.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-supp2-v2.docx

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75529/elife-75529-transrepform1-v2.pdf