The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF220 maintains hindbrain Hox expression patterns through regulation of WDR5 stability

eLife Assessment

This valuable study focuses on gene regulatory mechanisms essential for hindbrain development. Through molecular genetics and biochemistry, the authors propose a new mechanism for the control of Hox genes, which encode highly conserved transcription factors essential for hindbrain development. The strength of evidence is solid, as most claims are supported by the data. This work will be of interest to developmental biologists.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.94657.3.sa0Valuable: Findings that have theoretical or practical implications for a subfield

- Landmark

- Fundamental

- Important

- Valuable

- Useful

Solid: Methods, data and analyses broadly support the claims with only minor weaknesses

- Exceptional

- Compelling

- Convincing

- Solid

- Incomplete

- Inadequate

During the peer-review process the editor and reviewers write an eLife Assessment that summarises the significance of the findings reported in the article (on a scale ranging from landmark to useful) and the strength of the evidence (on a scale ranging from exceptional to inadequate). Learn more about eLife Assessments

Abstract

The spatial and temporal linear expression of Hox genes establishes a regional Hox code, which is crucial for the antero-posterior (A-P) patterning, segmentation, and neuronal circuit development of the hindbrain. RNF220, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, is widely involved in neural development via targeting of multiple substrates. Here, we found that the expression of Hox genes in the pons was markedly up-regulated at the late developmental stage (post-embryonic day E15.5) in Rnf220-/- and Rnf220+/- mouse embryos. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed different Hox de-repression profiles in different groups of neurons, including the pontine nuclei (PN). The Hox pattern was disrupted and the neural circuits were affected in the PN of Rnf220+/- mice. We showed that this phenomenon was mediated by WDR5, a key component of the TrxG complex, which can be polyubiquitinated and degraded by RNF220. Intrauterine injection of WDR5 inhibitor (WDR5-IN-4) and genetic ablation of Wdr5 in Rnf220+/- mice largely recovered the de-repressed Hox expression pattern in the hindbrain. In P19 embryonal carcinoma cells, the retinoic acid-induced Hox expression was further stimulated by Rnf220 knockdown, which can also be rescued by Wdr5 knockdown. In short, our data suggest a new role of RNF220/WDR5 in Hox pattern maintenance and pons development in mice.

Introduction

The coordinated expression of Hox genes clusters is critical for axial patterning to determine the positional identities during the development of many tissues, including the hindbrain (Frank and Sela-Donenfeld, 2019; Parker et al., 2014; Parker and Krumlauf, 2020; Pöpperl and Featherstone, 1993). In mammals, there are 39 Hox genes organized in four clusters (Hoxa, Hoxb, Hoxc, and Hoxd) and divided into 1–13 paralog groups (PG). During vertebrate development, the hindbrain forms eight metameric segmented units along the antero-posterior (A-P) axis known as rhombomeres (r), which give rise to the cerebellum, pons, and medulla later on Ghosh and Sagerström, 2018; Parker and Krumlauf, 2020. In the embryonic hindbrain, Hox1-5 genes are expressed in a nested overlapping pattern with rhombomere-specific boundaries. This Hox code is critical for the establishment of rhombomeric territories and the determination of cell fates (Barsh et al., 2017; Parker et al., 2016; Parker and Krumlauf, 2020).

At later embryonic stages, Hox genes also play vital roles in neuronal migration and circuit formation (Feng et al., 2021; Hockman et al., 2019; Kratochwil et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013). For example, neurons in the pontine nuclei (PN), which acts as an information integration station between the cortex and cerebellum (Kratochwil et al., 2017; Maheshwari et al., 2020), originate at the posterior rhombic lip of r6-r8, migrate tangentially to the rostral ventral hindbrain, and then receive different inputs from the cortex, in which the specific expression pattern of Hox3-5 genes determines the migration routines, cellular organization, and neuronal circuits (Geisen et al., 2008; Kratochwil et al., 2017; Maheshwari et al., 2020; Di Meglio et al., 2013; Lizen et al., 2017). Note that Hox gene expression is maintained up to postnatal and even adult stages in the hindbrain derivatives (Farago et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2021; Kratochwil et al., 2017).

Hox pattern maintenance is generally governed by epigenetic regulators, especially the polycomb-group (PcG) and trithorax-group (trxG) complexes, which repress and activate Hox genes, respectively (Bahrampour et al., 2019; Chopra et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2022; Papp and Müller, 2006). In mammals, different SET/MLL proteins and a common multi-subunit core module consisting of WDR5, RBBP5, ASH2L, and DPY-30 (WRAD) constitute the COMPASS (complex of proteins associated with Set1) family of TrxG complexes, which acts as a methyltransferase generally (Cenik and Shilatifard, 2021; Jambhekar et al., 2019; Schuettengruber et al., 2017). Among them, WDR5 plays a central scaffolding role and has been shown to act as a key regulator of Hox maintenance (Wang et al., 2011; Wysocka et al., 2005). WDR5 was also reported for HOX maintenance in human and associated with various blood and solid tumors. In acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, WDR5 is responsible for MLL-mediated HOXA9 activation and is a potential drug target (Chen et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). In addition, WDR5 facilitates HOTTIP, a long noncoding RNA, to recruit the MLL complex and thus stimulate HOXA9 and HOXA13 expression during the progression of prostate and liver tumors (Fu et al., 2017; Malek et al., 2017; Quagliata et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2020).

The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF220 is widely involved in neural development through targeting a range of proteins (Kim et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2022Wang et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2022c). Although our previous reports have shown that Rnf220-/- mice is neonatal lethal and the survived Rnf220+/- mice develop severe motor impairments, the underlying mechanisms remain incompletely understood (Ma et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2019). In the present study, a markedly up-regulation of Hox genes is observed in the pons of both Rnf220+/- and Rnf220-/- mice during late embryonic development. In consequence, the topographic input connectivity of the PN neurons with cortex is disturbed in Rnf220+/- mice. Furthermore, we identified WDR5 as a direct target of RNF220 for K48-linked ubiquitination and thus degradation, a mechanism critical for Hox de-repression by Rnf220 knockout. Together, these findings reveal a novel role for RNF220 in the regulation of Hox genes and pons development in mice.

Results

Rnf220 insufficiency leads to dysregulation of Hox expression in late embryonic pons

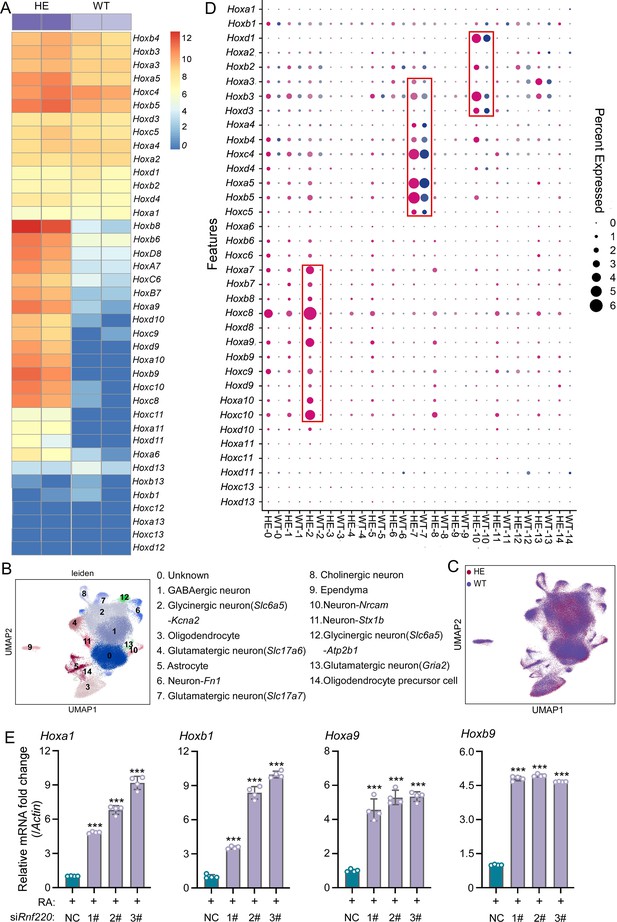

Rnf220 is strongly expressed in the embryonic mouse mid/hindbrain (Ma et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Based on microarray analysis, we explored changes in expression profiles in E18.5 Rnf220+/- and Rnf220-/- mouse brains, which breed floxed Rnf220 to Vasa-Cre mice. Interestingly, several Hox genes were up-regulated in the mouse brain of both genotypes (Supplementary file 1, Supplementary file 2). Considering that Hox expression in forebrain is too low (data not shown), we focus on the hindbrain and found that this phenomenon was observed only in late embryonic stages after E15.5 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Since Rnf220-/- mice is neonatal lethal and there is not significant difference in the upregulation of Hox genes between Rnf220+/- and Rnf220-/- mice, Rnf220+/- mice were used in subsequent assays in this study. To determine the specific brain regions with aberrant Hox expression, we examined the expression levels of Hoxa9 and Hoxb9, two of the most significantly up-regulated genes, in different brain and spinal regions (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A–D). Notably, both Hoxa9 and Hoxb9 were exclusively up-regulated in the brainstem of Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 2C and D). The brainstem comprises the midbrain, pons, and medulla (Figure 1—figure supplement 2E). Further, we confirmed that the up-regulation of Hox genes was restricted to the pons in the Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 2F). In addition, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of the pons also revealed an overall increase in Hox gene expression in adult Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 1A).

Hox genes up-regulated in pons of Rnf220+/- mice.

(A) The heatmap of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data showing Hox genes expression in pons of WT or Rnf220+/- mice (n=2 mice per group). (B–C) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) diagram showing 15 identified cell clusters annotated by single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) analysis of pons. Each dot represents a single cell, and cells are laid out to show similarities (n=3 mice per group). Genes in parentheses represent the marker genes of the cell group, while the genes following ‘-’ represent the specific genes of this cell group. (D) Heatmap of snRNA-seq data showing Hox expression changes in each cell cluster. (E) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis showing mRNA levels of indicated Hox genes in P19 cells when endogenous Rnf220 was knocked down by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in the presence of RA. WT, wild-type; HE, heterozygote; RA, retinoic acid. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To identify the specific cell populations in which Hox genes were up-regulated, we conducted single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) analysis of the pons of adult wild-type (WT) and Rnf220+/- mice. In total, 125,956 and 122,266 cell transcriptomes with an average of approximately ≥700 genes for the WT and Rnf220+/- mice respectively were further analyzed. 15 cell clusters were identified by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) in both the WT and Rnf220+/- groups (Figure 1B and C). When we annotate these cell clusters by their uniquely and highly expressed markers (Supplementary file 3), we found that most of the clusters were identified as distinct neuronal groups (cluster_1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 13), in addition to astrocyte (cluster_5), oligodendrocyte (cluster_3), oligodendrocyte precursor (cluster_14), ependymal cell (cluster_9), and a group not corresponding to any known cell types (cluster_0) (Figure 1B). Then, the Hox gene expression levels for each cell clusters were analyzed and found that up-regulation of Hox genes was most pronounced in three of these clusters (cluster_2, 7, and 10) (Figure 1D), albeit with distinct profiles. Hox7-10 genes were up-regulated genes in cluster_2, while Hox3-5 and Hox1-3 genes were activated in cluster_7 and 10, respectively (Figure 1D). These findings indicate that Hox genes were specifically up-regulated in the pons of Rnf220+/- mice from late developmental stages on.

P19 embryonal carcinoma cells can be induced to differentiate and express Hox genes upon retinoic acid (RA) administration and have been used to study Hox regulation (Vanderheyden and Defize, 2003Vanderheyden and Defize, 2003; Kondo et al., 1992; Pöpperl and Featherstone, 1993Pöpperl and Featherstone, 1993; Figure 1—figure supplement 3A). Here, we tested the effects of Rnf220 knockdown on RA-induced Hox gene activation in P19 cells. Rnf220 knockdown further enhanced the activation of many Hox genes, including Hoxa1, Hoxb1, Hoxa9, and Hoxb9, by RA presence (Figure 1E), suggesting a general role of Rnf220 in Hox regulation. Note that Rnf220 knockdown had no clear effect on Hox expression in the absence of RA (Figure 1—figure supplement 3B).

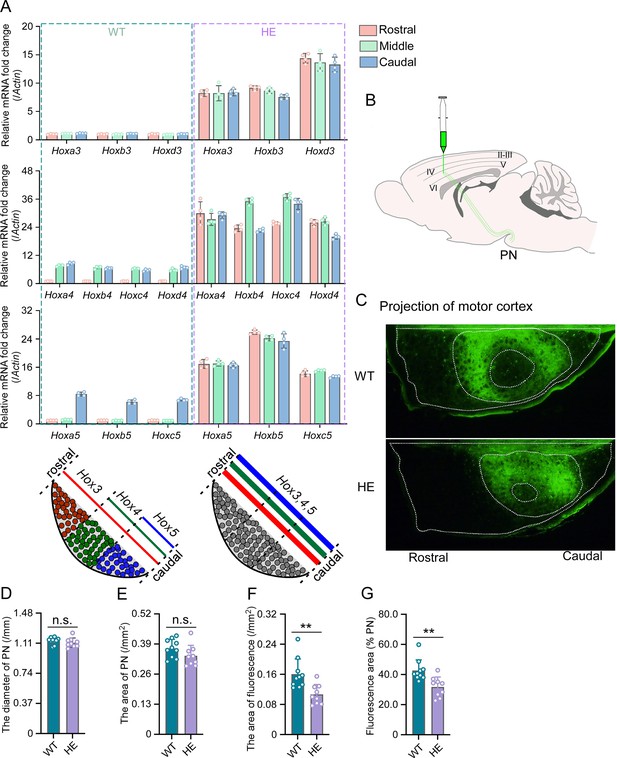

Rnf220 insufficiency disturbs Hox expression pattern and the neuronal circuit formation in the PN

When we refer to the transcriptomic profiles of each cluster in the pons, we found that the cluster_10 likely represents cells derived from rhombomeres 2–5, given their expression of endogenous anterior Hox genes (Hox1-3), while the cluster_7 likely represents cells derived from rhombomeres 6–8, as evidenced by the expression of Hox3-5 (Figure 1D). After mapping known neuron-specific markers to each cluster, PN-specific markers, including Nfib, Pax6, and Barhl1, were enriched in the cluster_7 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) results showed that compared to WT mice, some PN markers were up-regulated in Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). Originating at the posterior rhombic lip and migrating tangentially to their final position in the ventral part of the pons, PN neurons serve as relay cells between the cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Di Meglio et al., 2013; Kratochwil et al., 2017; Maheshwari et al., 2020). The expression pattern of Hox genes is crucial for the migration and the final neuronal circuit formation of the PN neurons (Kratochwil et al., 2017; Maheshwari et al., 2020). We analyzed the expression pattern of the endogenous Hox genes, including Hox3-5, in the PN neurons and the connection between the cortex and the PN neurons in Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 2; Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). The results of RT-PCR assays indicated an up-regulation in Hox4-5 expression levels in the Rnf220+/- PN (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). In the PN, endogenous Hox3-5 genes exhibit a nested and unique expression pattern along the rostral-caudal axis, with Hox3 ubiquitously expressed throughout the PN, Hox4 localized to the middle and posterior regions, and Hox5 confined to the posterior segment (Kratochwil et al., 2017). Next, the PN was evenly dissected into the rostral, middle, and caudal segments along the rostral-caudal axis and the endogenous expression pattern of Hox genes was examined in each section. The results showed that all the Hox3-5 paralogs were uniformly up-regulated along the rostral-caudal axis in the Rnf220+/- PN (Figure 2A).

Hox gene expression was dysregulated and motor cortex projections were disorganized in pontine nuclei (PN) of Rnf220+/- mice.

(A) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of relative expression levels of Hox3, Hox4, and Hox5 in rostral, middle, and caudal sections of PN in WT and Rnf220+/- mice. Expression level of each gene in rostral section of WT PN was set to 1 (n=5 mice per group). Bar graphs show the relative levels normalized against rostral group in the respective wild-type mice. (B) Diagram of experimental stereotactic injections. (C) Green fluoresce showed the projection from motor cortex to PNs in adult (2 months) WT and Rnf220+/- mice (n=10 in WT group and n=9 in Rnf220+/- group). (D–E) The diameter (D) and area (E) sizes of PN in WT and Rnf220+/- mice. Each data presents the average diameter and area sizes of PN from four consecutive slices for completely presenting circular fluorescence projections. (F) The area of fluorescence projection from motor cortex to PN in WT and Rnf220+/- mice. The sample used for statistics is consistent with the one selected in D–E. Each data represents the average fluorescence area of four consecutive slices. (G) The proportion of projected fluorescence area from motor cortex to PN area. The sample used for statistics is consistent with the one selected in D–E. WT, wild-type; HE, heterozygote. n.s., not significant. **p<0.01.

There is no difference of structure in PN or even pons between WT and Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A and B; Figure 2C–E). Considering the motor deficits of Rnf220+/- mice (Ma et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2019), the neuronal circuit between the motor cortex and the PN neurons were traced anterogradely by a non-transneuronal tracing virus (rAAV-hSyn-EGFP-WPRE-hGH-polyA) (Figure 2B). The results showed that fewer PN neurons were targeted by axons from the motor cortex in the Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 2C and F–G; Figure 2—figure supplement 2C). In addition, the projection from the motor cortex was centralized in the PN of Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 2C; Figure 2—figure supplement 2C).

Taken together, both the expression level/pattern of the endogenous Hox genes and the neuronal projection pattern from the motor cortex were disturbed by Rnf220 insufficiency in the mouse PN.

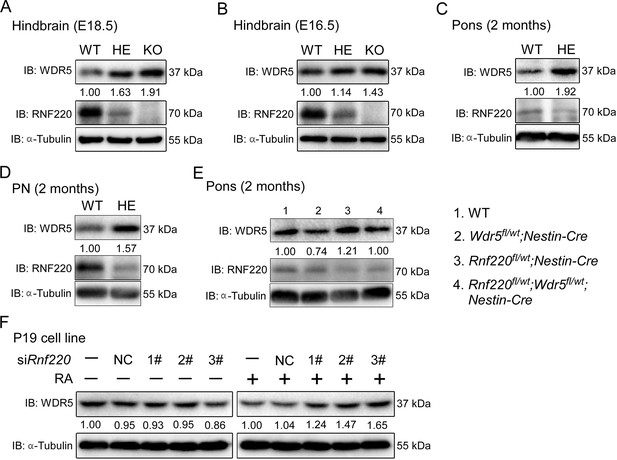

RNF220 targets WDR5 for K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation

The up-regulation of Hox genes in the Rnf220+/- mice suggested a role for RNF220 in the maintenance of Hox expression pattern. Generally, the Hox expression pattern is maintained epigenetically by the PcG and trxG complexes, which regulate the silencing and activation of Hox genes, respectively (Bahrampour et al., 2019; Chopra et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2022; Papp and Müller, 2006). Indeed, we did observe the local epigenetic modification changes, i.e., the down-regulated H3K27me3 signals and up-regulated H3K4me3 signals, in some Hox cluster in hindbrain of Rnf220+/- mice by ChIP-qPCR assays (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A and B). Therefore, protein levels of the core components of PcG and TrxG complexes in the mouse hindbrain and pons were examined and the results showed that although the protein levels of the core components of PcG we examined were comparable between WT and Rnf220+/-, a clear increase in the protein level of WDR5, a key component of the trxG complex, was observed in the hindbrain of both Rnf220+/-and Rnf220-/- mouse embryos at E18.5 (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A and B; Figure 3A), the phenomenon was also observed at E16.5 (Figure 3B). We next tested the expression of WDR5 in the mouse pons, cortex, and cerebellum at adult and found that the increase in the protein level of WDR5 was only observed in the pons, but not in the cortex or cerebellum, in Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 3C and E; Figure 3—figure supplement 2C and D), which is consistent with the pons-specific up-regulation in Hox genes expression. In addition, the protein level of WDR5 was also enhanced in the PN of Rnf220+/- mice (Figure 3D) and Rnf220 knockdown P19 cells in the presence of RA (Figure 3F).

RNF220 mediates WDR5 degradation.

(A–D) Western blots analysis showing the protein level of WDR5 in the indicated brain tissues of mice with different genotypes at different ages. (E) Western blot analysis showing WDR5 levels in the pons of adult mice with indicated genotypes. (F) Western blot analysis of protein levels of WDR5 in P19 cells with Rnf220 knockdown or not in the presence or absence of RA. IB, immunoblot; WT, wild-type; HE, heterozygote; KO, knockout; PN, pontine nuclei; NC, negative control; RA, retinoic acid.

The above data suggest that WDR5 might be a direct target of RNF220 for polyubiquitination and thus degradation. Indeed, in HEK293 cells transiently co-transfected with FLAG-tagged RNF220 and myc-tagged WDR5, WDR5 co-immunoprecipitated with RNF220 (Figure 4A). In the reverse experiment, RNF220 also co-immunoprecipitated with WDR5 (Figure 4B). Furthermore, in the brainstem, when WDR5 was immunoprecipitated using an anti-WDR5 antibody, endogenous RNF220 was also detected in the immunoprecipitate. Then we examined if the WDR5 protein level was regulated by RNF220. The results showed that co-expression of WT RNF220, but not the ligase-dead mutant (W539A) or the RING domain deletion (△Ring) form, clearly reduced the protein level of WDR5 in HEK293 cells (Figure 4D). In addition, the reduction in the protein level of WDR5 by RNF220 overexpression was blocked by MG132, suggesting a role for the proteasome in this regulation (Figure 4E).

RNF220 interacts with and targets WDR5 for K48-linked polyubiquitination.

(A–B) Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis of interactions between RNF220 and WDR5 in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were transfected with indicated plasmids and harvested after 48 hr. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Whole-cell lysate and immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. (C) Endogenous co-immunoprecipitation analysis showing the interaction between RNF220 and WDR5 in hindbrains of WT mice. (D) Western blots analysis shows the protein level of WDR5 when co-expressed with wild-type or mutated RNF220 in HEK293 cells. (E) Western blots analysis shows the protein level of WDR5 when co-expressed with RNF220 in HEK293 cells in the presence of MG132 (10 mM) or not. (F) In vivo ubiquitination assays showing the ubiquitination status of WDR5 when co-expressed with WT or mutated RNF220 in HEK293 cells. (G) In vivo ubiquitination assays showing the ubiquitination status of WDR5 in hindbrains of WT and Rnf220+/- mice. (H) In vivo ubiquitination assays showing RNF220-induced polyubiquitination of WDR5 when the indicated ubiquitin mutations were used in HEK293 cells. (I) In vivo ubiquitination assays showing the ubiquitination status of the indicated WDR5 mutants when co-expressed with WT or ligase-dead RNF220 in HEK293 cells. WT, wild-type; HE, heterozygote; KO, knockout; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation; UB, ubiquitin; WCL, whole-cell lysate; △Ring, RNF220 Ring domain deletion; W539R, RNF220 ligase dead mutation; K48, ubiquitin with all lysines except the K48 mutated to arginine; K48R, ubiquitin with the K48 was substituted by an arginine; 3KR, substitution of lysines at the positions of 109, 112, and 120 in WDR5 with arginines simultaneously.

We further carried out polyubiquitination assays to examine if WDR5 may be a target for RNF220. It was found that co-expression of RNF220 strongly enhanced the polyubiquitination of WDR5 protein, and this regulation depends on the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of RNF220 because RNF220△Ring failed to promote the polyubiquitination of WDR5 (Figure 4F). Moreover, when the endogenous WDR5 protein was immunoprecipitated from the mouse pons, its polyubiquitination level in Rnf220+/- mice was markedly decreased compared to WT mice (Figure 4G).

Different types of ubiquitination linkages have distinct regulatory effects on the stability or activity of protein targets, and K48-linked polyubiquitination usually leads to proteasomal degradation of protein targets (Grice and Nathan, 2016Grice and Nathan, 2016.). Indeed, WDR5 were only ubiquitinated by RNF220 when K48-type ubiquitin was present (Figure 4H). Consistent with this, when the K48R mutated ubiquitin was co-expressed, the RNF220-induced polyubiquitination level of WDR5 protein was fully diminished (Figure 4H). To determine the exact lysines ubiquitinated by RNF220, we first tested the effects of RNF220 on the stability of different WDR5 truncates and found that the truncate remaining 1-127aa was enough to be degraded by RNF220, suggesting the corresponding lysines were included in this region (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A). We individually mutated all these conserved lysines into arginines and then examined RNF220-mediated ubiquitination of each mutant. It was found that K109, K112, and K120 were required for the polyubiquitination of WDR5 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1B). Furthermore, when these lysine residues were simultaneously mutated into arginines, RNF220 failed to enhance the polyubiquitination levels of the resulted WDR5-3KR mutants (Figure 4I), suggesting that these lysine residues are direct ubiquitination sites. Together, these results indicate that RNF220 regulates WDR5 ubiquitination by adding K48-linked polyubiquitin chains at the lysine sites of K109, K112, and K120.

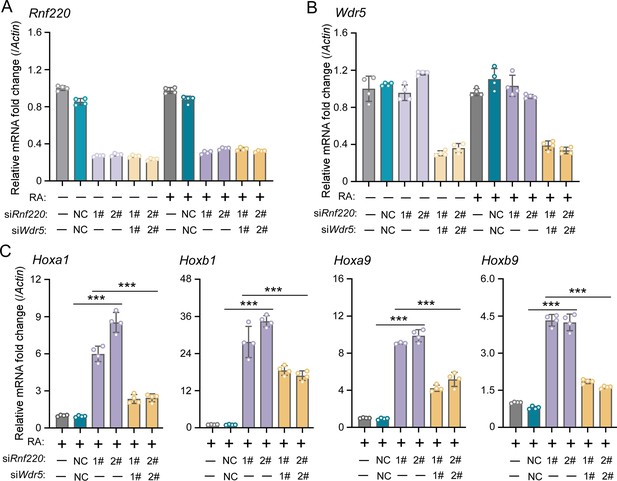

The maintenance of Hox expression by RNF220 depends on its regulation to WDR5

To investigate the requirement of the RNF220-mediated regulation to WDR5 in Hox expression maintenance by RNF220, we first examined whether Wdr5 knockdown could mitigate the impact of Rnf220 knockdown on Hox expression in P19 cells in the presence of RA. It is observed that the stimulation of Hox genes by Rnf220 knockdown was significantly reduced when Wdr5 was knocked down simultaneously by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in the presence of RA (Figure 5A–C). Note that the expression levels of Hox genes showed no clear changes when without RA or only Wdr5 was knocked down in P19 cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A and B).

WDR5 recovered Rnf220 deficiency-induced up-regulation of Hox genes in P19 cell line.

(A–B) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis showing the expression levels of Rnf220 (A) and Wdr5 (B) when transfected the indicated combinations of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against Rnf220 or Wdr5 in the presence or absence of RA. Bar graphs show the relative levels normalized against control group without siRNA or RA treatment. (C) qRT-PCR analysis showing the expression levels of Hoxa1, Hoxb1, Hoxa9, Hoxb9 when siRnf220, together with siWDR5 or not, were transfected in P19 cells treated with RA. RA, retinoic acid. n.s., not significant; ***p<0.001.

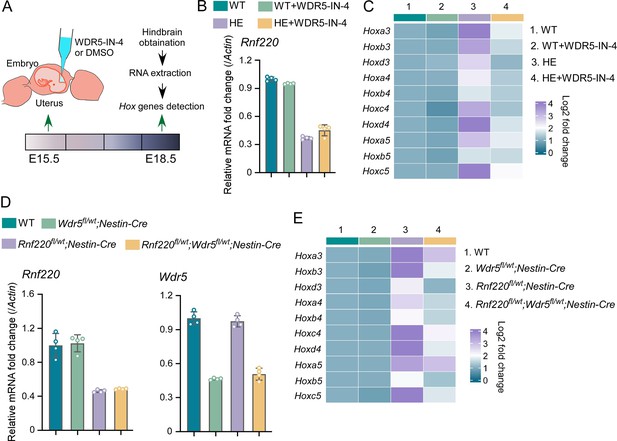

Using in utero microinjection, we tested the effects of WDR5 inhibition by WDR5-IN-4, an established WDR5 inhibitor (Aho et al., 2019), on the up-regulation of Hox genes in hindbrains of the Rnf220+/- mice at late embryonic stages (Figure 6A). It was found that the up-regulation of Hox3-5 genes in the hindbrain of the Rnf220+/- embryos was largely reversed by WDR5-IN-4 (Figure 6C). Notably, we found that WDR5-IN-4 injection had no effect on the endogenous Rnf220 expression in the hindbrain (Figure 6B). Last, the effect of genetic ablation of Wdr5 in neural system on the up-regulation of Hox genes in RNF220 hypoinsufficient mice was examined. Considering Wdr5+/- mice is embryonic lethal, and the up-regulation of Hox genes could also be observed in the hindbrains of Rnf220fl/wt;Nestin-Cre mice, we used Rnf220 fl/wt;Nestin-Cre and Wdr5fl/wt mice to generate WT, Rnf220fl/wt;Nestin-Cre, Wdr5fl/wt;Nestin-Cre, and Rnf220fl/wt;Wdr5fl/wt;Nestin-Cre mice (Figure 6D). It was found that the up-regulation of Hox3-5 genes in the pons of Rnf220fl/wt;Nestin-Cre mice were markedly recovered by Wdr5 genetic ablation in Rnf220fl/wt;Wdr5fl/wt;Nestin-Cre mice (Figure 6E). ChIP-qPCR also showed the local epigenetic modification changes in some Hox cluster, with H3K27me3 up-regulated and H3K4me3 down-regulated in Rnf220 and Wdr5 double knockdown P19 cell line related to Rnf220 single knockdown P19 cell line in the presence of RA (Figure 6—figure supplement 1).

Genetic and pharmacological ablation of WDR5 recovered Rnf220 deficiency-induced up-regulation of Hox genes.

(A) Diagram of experimental strategy for in utero local injection of WDR5 inhibitors. (B–C) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of expression levels of Rnf220 (B), Hox3-Hox5 (C) in hindbrains of WT and Rnf220+/- mouse embryos treated with WDR5 inhibitors or not at E18.5 (n=3 mice per group). Actin was used as the internal controls (C). Heatmap of Hox expression showed the relative levels normalized against WT group. (D–E) qRT-PCR analysis of expression levels of Rnf220 (D), Wdr5 (D), Hox3-Hox5 (E) in pons of P15 mice with indicated genotypes (n=2 mice per group). Gapdh was used as the internal controls (E). Heatmap of Hox expression showed the relative levels normalized against WT group. WT, wild-type; HE, heterozygote.

Taken together, Rnf220 dificiency induces the up-regulation of Hox genes in the mouse hindbrain and thus a defects in cortex-PN nueronal circuits. Mechanistically, we found that RNF220 regulates the protein stability of WDR5 via ubiquitination in the mouse hindbrain. WDR5 conditional knockdown or functional inhibition reversed the up-regulation of Hox genes expression in Rnf220 deficient mice. The above findings support the involvement of WDR5 regulation by RNF220 in the maintenance of Hox expression pattern in the mouse hindbrain.

Discussion

During early embryonic development, the Hox genes are collinearly expressed in the hindbrain and spinal cord along the A-P axis to guide regional neuronal identity. Later on, the segmental Hox gene expression pattern in the hindbrain is maintained till at least early postnatal stages. The Hox genes are also expressed in adult hindbrains with restricted anterior boundaries (Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Miller and Dasen, 2024; Di Bonito et al., 2013). In addition to their roles in progenitor cell specification, cell survival, neuronal migration, axon guidance, and dendrite morphogenesis during early development stages (Smith and Kratsios, 2024), Hox genes also play key roles in the regulation of synapse formation, neuronal terminal identity, and neural circuit assembly at late stages (Feng et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2021; Philippidou and Dasen, 2013). Our study revealed a dose-dependent role of RNF220 and WDR5 in the maintenance of Hox expression in the hindbrain, which might have a functional role in the neural circuit organization of the pons in mice.

In mammals, WDR5, a key component of the COMPASS-related complexes, has been reported to be absolutely required for the regulation of Hox genes expression during mammalian embryo development and cancer progression via different mechanisms (Wysocka et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). Here, we report a WDR5 protein stability controlling mechanism by RNF220-mediated polyubiquitination and illustrate the role of this regulation on the maintenance of Hox genes expression in the mouse hindbrain. The stabilization of WDR5 and stimulation of Hox expression upon RNF220 knockdown was also recapitulated in RA-treated P19 cells, a cellular model for Hox regulation study.

Interestingly, when examined at single cell level, different Hox stimulation profiles were detected in different neuronal groups, so that Hox1-3 were up-regulated in cluster 10, while Hox3-5 and Hox7-10 up-regulation appeared in cluster 7 and cluster 2, respectively (Figure 1D). Clusters 10 and 7 express endogenous Hox1-3 and Hox3-5, respectively. It is reasonable that the expression of these Hox genes is stimulated upon WDR5 elevation due to RNF220 insufficiency. Cluster 2 is most interesting in that, Hox7-10 were up-regulated in these cells which were not expressed in WT hindbrain. This cluster was defined as glycinergic neuron cells by specific Slc6a5 expression. The nature of this group of cells and the phenotypic effect of Hox up-regulation await further analysis. The de-regulation of Hox genes might have wide effect on the development of many nuclei in the pons, including cell differentiation and neural circuit formation. For the PN, we showed here that the patterning and projection pattern from the motor cortex were affected in the Rnf220+/- mice.

The regulation of WDR5 and Hox expression by RNF220 seems to be context dependent and precisely controlled in vivo, depending on the molecular and epigenetic status of the cell. For example, although WDR5 and RNF220 are widely co-expressed in the brain, WDR5 levels are not affected in most regions in the Rnf220+/- brain, including the cortex, cerebellum, etc. (Figure 3—figure supplement 2C and D). This is also true for EED, another epigenetic regulator, which is targeted by RNF220 in the cerebellum, but not in the pons (Ma et al., 2020). In untreated P19 cells, knockdown of RNF220 also has no effect on the stability of endogenous WDR5, although overexpression of RNF220 did reduce WDR5 level in 293T cells. We suggest that RA treatment of P19 cells helps to set up the molecular environment that facilitates Hox expression as well as RNF220-WDR5 interaction.

In summary, our data support WDR5 as a RNF220 target involved in the maintenance of Hox expression and thus development of the pons.

Materials and methods

Mouse strains and genotyping

Request a detailed protocolAll procedures involving mice were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IACUC-PA-2021-07-018). Mice were housed under standard conditions at a temperature range of 20–22°C, humidity of 30–45%, and 12 hr light/dark cycle. Rnf220 floxed mice (Rnf220fl/fl) were originally 129Sz/SvPasCrl background and mated with C57BL/6 then. Other mice used were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. Vasa-Cre mice were used to mate with Rnf220 floxed mice (Rnf220fl/fl) to generate Rnf220 germ cell knockout (Rnf220-/-) or heterozygote (Rnf220+/-) mice. Nestin-Cre mice were used to mate with Rnf220fl/fl and Wdr5 floxed mice (Wdr5fl/fl) to generate conditional neural specific knockout or heterozygote mice. Rnf220fl/wt;Wdr5fl/wt;Nestin-Cre mice were obtained by crossing Rnf220fl/wt;Nestin-Cre with Wdr5fl/wt mice.

Genotypes were determined by PCR using genome DNA from tail tips as templates. PCR primers were listed as follows: 5’-CTG TTG ATG AAG GTC CTG GTT-3’ and 5’-CAG GAA AAT CAA TAG ACA ACT T-3’ were used to detect Rnf220 floxP carrying. 5’-CTG TTG ATG AAG GTC CTG GTT-3’ and 5’-CTG ATT TCC AGC AAC CTA AA-3’ were used to detect Rnf220 knockout. 5’-GCC TGC ATT ACC GGT CGA TGC-3’ and 5’-CAG GGT GTT ATA AGC AAT CCC-3’ were used for Cre positive detection. 5’-GAA TAA CTA CTT TCC CTC AGA CC-3’ and 5’-CAG GCC AAG TAA CAG GAG GTA G-3’ were used to detect Wdr5 floxP carrying. 5’-GAA TAA CTA CTT TCC CTC AGA CC-3’ and 5’-AGA CCC TGA GTG AGG ATA CAT AA-3’ were used to detect Wdr5 knockout.

Cell culture

Request a detailed protocolThe HEK293 cell line was from Conservation Genetics CAS Kunming Cell Bank (KCB 200408YJ) and P19 cell line was a generous gift from Dr. NaiheJing (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, CAS). Both cell lines were verified by STR matching analysis and tested negative for mycoplasma. Both HEK293 and P19 cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, C11995500BT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biological Industries, 04-001-1A), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Biological Industries, 03-031-1B). Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. 0.5 μM RA (Sigma, R2625) was used to induce Hox expression in P19 cells.

To achieve gene overexpression or knockdown, HEK293 and P19 cells were transfected by Lipo2000 (Invitrogen, 11668500) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following siRNAs (RiboBio) were used for Rnf220 or Wdr5 knockdown in P19 cells: siG2010160325456075, siG2010160325457167, and siG2010160325458259 were used for Rnf220 knockdown; siB09924171210, siG131113135429, and siG131113135419 were used for Wdr5 knockdown.

Total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Request a detailed protocolTissue and cells were homogenized with 1 mL TRIzol (TIANGEN, DP424), after which 200 μL of chloroform was added to the lysates for phase separation. After centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 min at 4°C, the aqueous phase (500 μL) was transferred to a new tube and mixed with equal volumes of isopropanol for RNA precipitation. After 30 min, RNA pellets were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 min at 4°C, twice washed with 75% ethanol, and dissolved in DNase/RNase-free water.

cDNA was synthesized with Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, K1632) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All reactions were performed at least triplicates with Light Cycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, 04707516001). Primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

| Genes | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| Actin | GCCAACCGTGAAAAGATGAC | GAGGCATACAGGGACAGCAC |

| Gapdh | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

| Rnf220 | GTCTCAGTAGACAAGGACGTTCACA | GGGGTGGAGGTGTAGTAAGGAAG |

| Wdr5 | CGTGACAGGCGGGAAGTGGA | CGGGTGACAAGCCGTGGAAAT |

| Hoxa1 | AGCTCTGTGAGCTGCTTGGT | AAAAGAAACCCTCCCAAAACA |

| Hoxa2 | TGCCATCAGCTATTTCCAGG | GATGAAGGAGAAGAAGGCGG |

| Hoxa3 | TCTTAACATGGAGGGAGCCA | TCTGAAGGCTACGTGTGCTG |

| Hoxa4 | ACGCTGTGCCCCAGTATAAG | ACCTTGATGGTAGGTGTGGC |

| Hoxa5 | CAGGGTCTGGTAGCGAGTGT | CTCAGCCCCAGATCTACCC |

| Hoxa6 | GTCTGGTAGCGCGTGTAGGT | CCCTGTTTACCCCTGGATG |

| Hoxa7 | CTTCTCCAGTTCCAGCGTCT | AAGCCAGTTTCCGCATCTAC |

| Hoxa9 | GTAAGGGCATCGCTTCTTCC | ACAATGCCGAGAATGAGAGC |

| Hoxa10 | TCTTTGCTGTGAGCCAGTTG | CTCCAGCCCCTTCAGAAAAC |

| Hoxa11 | CCTTTTCCAAGTCGCAATGT | AGGCTCCAGCCTACTGGAAT |

| Hoxa13 | CGGTGTCCATGTACTTGTCG | AGCGGCTACTACCCGTGC |

| Hoxb1 | GGTGAAGTTTGTGCGGAGAC | TTCGACTGGATGAAGGTCAA |

| Hoxb2 | GAACCAGACTTTGACCTGCC | GAGCTGGAGAAGGAGTTCCA |

| Hoxb3 | ATCTGTTTGGTGAGGGTGGA | CCGCACCTACCAGTACCACT |

| Hoxb4 | GACCTGCTGGCGAGTGTAG | CTGGATGCGCAAAGTTCAC |

| Hoxb5 | CTGGTAGCGAGTATAGGCGG | AGGGGCAGACTCCACAGATA |

| Hoxb6 | TAGCGTGTGTAGGTCTGGCG | AGCAGAAGTGCTCCACGC |

| Hoxb7 | CTTTCTCCAGCTCCAGGGTC | AACTTCCGGATCTACCCCTG |

| Hoxb8 | GAACTCCTTCTCCAGCTCCA | CACAGCTCTTTCCCTGGATG |

| Hoxb9 | TCCAGCGTCTGGTATTTGGT | GAAGCGAGGACAAAGAGAGG |

| Hoxb13 | TGCCCCTTGCTATAGGGAAT | ATTCTGGAAAGCAGCGTTTG |

| Hoxc4 | CTAATTCCAGGACCTGCTGC | AAAAATTCACGTTAGCACGGT |

| Hoxc5 | TTCTCGAGTTCCAGGGTCTG | ATTTACCCGTGGATGACCAA |

| Hoxc6 | CAGGGTCTGGTACCGAGAGTA | TCCAGATTTACCCCTGGATG |

| Hoxc8 | CAAGGTCTGATACCGGCTGT | ATCAGAACTCGTCTCCCAGC |

| Hoxc9 | AATCTGTCTCTGTCGGCTCC | AGTCTGGGCTCCAAAGTCAC |

| Hoxc10 | ACCTCTTCTTCCTTCCGCTC | ACTCCAGTCCAGACACCTCG |

| Hoxc11 | AAATGAAGGCTCCTACGGCG | TGTCGAAGAAGCGGTCGAAA |

| Hoxc12 | AATACGGCTTGCGCTTCTT | GACCCTGGCTCTCTGGTTTC |

| Hoxc13 | CTCACTTCGGGCTGTAGAGG | TCAGGTGTACTGCTCCAAGG |

| Hoxd1 | TCTGTCAGTTGCTTGGTGCT | TGAAAGTGAAGAGGAACGCC |

| Hoxd3 | ACCAGCTGAGCACTCGTGTA | AGAACAGCTGTGCCACTTCA |

| Hoxd4 | CTCCCTGGGCTGAGACTGT | CCCTGGGAACCACTGTTCT |

| Hoxd8 | GCCCGCGAAGTTTTACGGAT | TAAGTGGTCTGGGTCCTCGC |

| Hoxd9 | TTGTTTGGGTCAAGTTGCTG | CTCAGCTTGCAGCGATCA |

| Hoxd10 | TCTCCTGCACTTCGGGAC | GGAGCCCACTAAAGTCTCCC |

| Hoxd11 | AGTGAGGTTGAGCATCCGAG | ACACCAAGTACCAGATCCGC |

| Hoxd12 | TGCTTTGTGTAGGGTTTCCTCT | CTTCACTGCCCGACGGTA |

| Hoxd13 | TGGTGTAAGGCACCCTTTTC | CCCATTTTTGGAAATCATCC |

| Unc5b | CGTGACAGGCGGGAAGTGGA | CGGGTGACAAGCCGTGGAAAT |

| Pax6 | AGACAACAACAAAGCGGACT | CTTCGCAAATGACAACTGAC |

| Barhl1 | TACCAGAACCGCAGGACTAAAT | AGAAATAAGGCGACGGGAACAT |

| Nfib | AGAAGCCCGAAATCAAGCAG | CCAGTCACGGTAAGCACAAA |

| Neph2 | ACAAGGTTCGGAAATGAAGTCG | GTTGCCATTAGGACGAGGAA |

ChIP-qPCR

Request a detailed protocolP19 cells or grinded mouse PN tissues were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 25 min, and stopped with addition of glycine. After gentle centrifuging, samples were collected and lysed with ChIP lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min on ice. Genomic DNA was sheared into 200–500 bp fragments by sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatants containing chromatin fragments were collected and immunoprecipitated with anti-IgG (2 μg, ProteinTech, B900610), anti-H3K27me3 (2 μg, Abcam, ab192985, RRID: AB_2650559), or anti-H3K4me3 antibodies (2 μg, Abcam, ab8580, RRID: AB_306649) at 4°C overnight. Then, the immunoprecipitates coupled with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz, sc-2003) were washed sequentially by a low salt washing buffer, high salt washing buffer, LiCl washing buffer, and TE buffer. The immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments were eluted by 500 μL elution buffer for reversal of cross-linking at 65°C overnight. Input or immunoprecipitated genomic DNA was purified by the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, 28104) and used as a template for quantification PCR. The primers we used were listed in Table 2.

Primers used for ChIP-qPCR.

| Genes | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxa1 | GCAGGACAAGGTTGATGGG | GCAGGTGGGAGGGACAGAT |

| Hoxa3 | GGACAGACTCGGTGGTAAGA | AGTTCATGTTCACGGTTCCTAT |

| Hoxa9 | GCAGGAAACACTTTGCCAGA | GCCCGAGTTAGGACCCGTA |

| Hoxa10 | CTCCTTGCCTCCTTCTTCC | CCTGGGTATCTGAGCATCTAA |

| Hoxb3 | CCGAGGACGGACCGAAGAT | CCCTGAACTGGACCACCAT |

| Hoxb4 | GAAGAACGCACGGAAAGTAAG | GGGAAAGAATATGAGCGGAGT |

| Hoxb7 | CCTTAGGGACGCCTTGGTC | ACGCAGGGATTGAATGTTCG |

| Hoxb8 | GCCATTGAATTTCTATCCCAC | GGTGAGGCAAGCTAAAGCAG |

| Hoxc6 | CTTCTCCTCTGCCCTCTTC | GTTAGTTAATACATGGACCTCT |

| Hoxc8 | GTCGTGGATTGATGAACGCG | TCTGCTCACTGTCGGTAGG |

| Hoxc9 | TGTGCCTTGAGTCACTTTGC | CTTGCTCCACTTCTCCAGAT |

| Hoxc10 | TTTTCTTTGGGTCCTCGTAAA | AGTCTAGGGAGCCATTTGTC |

| Hoxd3 | TTTTCCGAGTCCTATTGCTTG | CTGTATCATCTGCCCTCTATC |

| Hoxd8 | AGGACTTTGATTCGCTTTGATA | CGAGGTTGACGGATTGATTG |

| Hoxd9 | AACCTACCCTCGGAGATGC | GCACTGGAGTCCCAAGGAG |

| Hoxd10 | GGAGGGATGTTTCCGAACT | CACATACCCAGGCAGAACG |

In utero microinjection

Request a detailed protocolPregnant mice were administered isoflurane for deep anesthesia. Following this, a laparotomy was performed to carefully extract the embryos, which were then placed on a sterile surgical drape. WDR5-IN-4 (100 μg, MedChemExpress, HY-111753A), containing 0.05% Malachite Green reagent for tracing, was injected into the hindbrain of E15.5 embryos using a finely tapered borosilicate needle. To minimize the risk of spontaneous abortion, injections were spaced for the selected embryos. Following the injections, the uterus was returned to the abdominal cavity and infused with 2 mL of 37°C, 0.9% saline solution. The peritoneum and abdominal skin were then sutured. Finally, the mice were placed on a heating pad to facilitate recovery from anesthesia.

Ubiquitination assay, immunoprecipitation, and western blot analysis

Request a detailed protocolIn vivo ubiquitination, immunoprecipitation, and western blot assays were carried out as previously described (Ma et al., 2014). HEK293 cells were transfected in six-well plates, and at 48 hr post transfection cells were lysed in 500 μL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], and 1% Triton X-100) that contained a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) for 30 min on ice; mouse tissues were fully grinded and lysed with RIPA Strong Lysis (Beyotime, P0013B) containing a protease inhibitor mixture for 30 min on ice. Following centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, 50 μL supernatant was mixed with loading buffer and incubate boiled at 95°C for 5 min, the remaining supernatant was coated with antibody and A/G agarose beads (or FLAG beads) overnight. After washing five times, the bound proteins were eluted with SDS loading buffer at 95°C for 5 min. Final total lysates and immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. The following primary antibodies were used for botting: anti-RNF220 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA027578, RRID: AB_10601482), anti-WDR5 (D9E11) (Cell Signaling Technology, 13105, RRID: AB_2620133), anti-RING1B (D22F2) (Cell Signaling Technology, 5694S, RRID: AB_10705604), anti-SIN3B (AK-12) (Santa Cruz, sc-768, RRID: AB_2187787), anti-EZH2 (ProteinTech, 21800-1-AP, RRID: AB_10858790), anti-SUZ12 (Bethyl, A302-407A, RRID: AB_1907290), anti-RYBP (A-1) (Santa Cruz, sc-374235, RRID: AB_10989572), anti-CBX6 (H-1) (Santa Cruz, sc-393040, RRID: AB_2923357), anti-CBX7 (G-3) (Santa Cruz; sc-376274, RRID: AB_10989202), anti-CBX8 (C-3) (Santa Cruz, sc-374332, RRID: AB_10990104), anti-PHC1 (D-10) (Santa Cruz, sc-390880), anti-α-Tubulin (ProteinTech, 66031-1-Ig, RRID: AB_11042766), anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich; F-7425, RRID: AB_439687), anti-myc (ProteinTech; 16286-1-AP, RRID: AB_1182162), and anti-Ub (P4D1) (Santa Cruz, sc-2007, RRID: AB_631740).

snRNA-seq library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis

Request a detailed protocolsnRNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Split-seq platform (Butler et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2018). Freshly harvested mouse pons tissues underwent nuclear extraction following previously described protocols (Butler et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2018). In brief, mouse brain tissues were transferred into a 2 mL Dounce homogenizer containing 1 mL homogenizing buffer (250 mM sucrose, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH = 8.0], 1 mM DTT, RNase Inhibitor, and 0.1% Triton X-100). The mixture was subjected to five strokes with a loose pestle, followed by 10 strokes with a tight pestle. The resulting homogenates were filtered through a 40 μm strainer into 5 mL Eppendorf tubes and subsequently centrifuged for 4 min at 600×g and 4°C. The pellet was re-suspended and washed in 1 mL of PBS containing RNase inhibitors and 0.1% BSA. The nuclei were again filtered through a 40 μm strainer and quantified. These nuclei were partitioned into 48 wells, each of which contained a barcoded, well-specified reverse transcription primer, to enable in-nuclear reverse transcription. Subsequent second and third barcoding steps were carried out through ligation reactions. After the third round of barcoding, the nuclei were divided into 16 aliquots and lysed prior to cDNA purification. The resulting purified cDNA was subjected to template switching and qRT-PCR amplification, which was halted at the beginning of the plateau stage. Finally, the purified PCR products (600 pg) were used to generate Illumina-compatible sequencing libraries. Distinct, indexed PCR primer pairs were employed to label each library, serving as the fourth barcode.

The libraries underwent sequencing on the NextSeq system (Illumina) using 150-nucleotide kits and paired-end sequencing protocols. In this arrangement, Read 1 covered the transcript sequences and Read 2 contained the UMI and UBC barcode combinations. Initially, a six-nucleotide sequencing index, serving as the fourth barcode, was appended to the ends of Read 2. Subsequently, reads with more than one mismatching base in the third barcode were excluded from the dataset. Furthermore, reads containing more than one low-quality base (Phred score≤10) within the UMI region were also discarded. The sequencing results were aligned to exons and introns in the reference genome (Genome assembly GRCm38) and aggregated intron and exon counts at the gene level were calculated by kallisto and bustools software as described (https://bustools.github.io/BUS_notebooks_R).

Following export of the matrix, quality control measures were performed to remove low-quality cells and potential doublets, as described previously (Rosenberg et al., 2018). After filtering, a total of 125,956 and 122,266 cells for WT and Rnf220+/- pons respectively remained for subsequent analysis. Seurat v2 (Butler et al., 2018.) was used to identify HVGs within each group. Principal component analysis and UMAP were performed to embed each cell from the reduced principal component space on a 2D map. Then clustering of cell populations and identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were carried out as previously described (Ma and Mao, 2022b). We annotated the embryonic cell populations and lineages based on their DEGs (Supplementary file 3).

Mouse brain stereotactic injection and neuronal tracing

Request a detailed protocolMouse brain stereotactic injection and neuronal tracing were carried out as previously described with minor modifications (Xu et al., 2021). Adult mice (2–3 months of age) were used for anterograde monosynaptic neuronal tracing. The mice were first deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and placed into a stereotactic apparatus with the front teeth latched onto the anterior clamp. The mouth and nose of the mice were covered with a mask to provide isoflurane and keep them in an anesthetic state during the operation. The head was adjusted and maintained in horizontal by inserting ear bars into the ear canal. The hair of the head was shaved with an electric razor and cleaned using a cotton swab which was dipped in 75% alcohol. Cut the scalp along the midline with surgical scissors and make sure the bregma, lambda, and the interaural line were exposed. The intersection between the lambda and interaural line was set to zero. The coordinates ±1.75, –4.9, −1.65 were applied for motor cortex localization. Each mouse received a single injection of 500 nL of rAAV-hSyn-EGFP-WPRE-hGH-poly A (Brainvta, PT-1990) viral fluid in the hemisphere. After the injection, mice were bred for another 3 weeks for neuronal tracing before their brains were harvested for analysis.

Slice preparation

Request a detailed protocolMice subjected to stereotactic injection were euthanized, and whole brains were collected for the preparation of frozen sections. Following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (diluted in PBS) for 48 hr, the brains were successively treated with 20% sucrose (diluted in PBS) for 48 hr and 30% sucrose for 24 hr. Brain tissues were then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (SAKURA, 4583) at −20°C and sliced along the sagittal plane at a thickness of 40 μm.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolPN and fluorescence length and area were statistically analyzed by ImageJ software (National Institute of Health). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). All experiments were repeated at least two times. Comparisons were performed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. p-Values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*), 0.01 were considered statistically significant (**), and 0.001 were considered statistically significant (***).

Data availability

All the snRNA-seq and RNA-seq raw data have been deposited in the GSA (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/) with accession number is CRA013111.

-

Genome Sequence ArchiveID CRA013111. Hindbrain pattern maintenance in mouse.

References

-

COMPASS and SWI/SNF complexes in development and diseaseNature Reviews. Genetics 22:38–58.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0278-0

-

Hox genes and region-specific sensorimotor circuit formation in the hindbrain and spinal cordDevelopmental Dynamics 242:1348–1368.https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24055

-

Emerging roles for hox proteins in the last steps of neuronal development in worms, flies, and miceFrontiers in Neuroscience 15:801791.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.801791

-

Hindbrain induction and patterning during early vertebrate developmentCellular and Molecular Life Sciences 76:941–960.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-018-2974-x

-

Developing roles for hox proteins in hindbrain gene regulatory networksThe International Journal of Developmental Biology 62:767–774.https://doi.org/10.1387/ijdb.180141cs

-

The recognition of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasomeCellular and Molecular Life Sciences 73:3497–3506.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2255-5

-

Roles and regulation of histone methylation in animal developmentNature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 20:625–641.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0151-1

-

The regulation of the murine Hox-2.5 gene expression during cell differentiationNucleic Acids Research 20:5729–5735.https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/20.21.5729

-

RNF220, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets Sin3B for ubiquitinationBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 393:708–713.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.066

-

HOXA5 localization in postnatal and adult mouse brain is suggestive of regulatory roles in postmitotic neuronsThe Journal of Comparative Neurology 525:1155–1175.https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.24123

-

The ubiquitin ligase RNF220 enhances canonical Wnt signaling through USP7-mediated deubiquitination of β-cateninMolecular and Cellular Biology 34:4355–4366.https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00731-14

-

Haploinsufficiency of the TDP43 ubiquitin E3 ligase RNF220 leads to ALS-like motor neuron defects in the mouseJournal of Molecular Cell Biology 13:374–382.https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjaa072

-

The many faces of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, RNF220, in neural development and beyondDevelopment, Growth & Differentiation 64:98–105.https://doi.org/10.1111/dgd.12756

-

Establishing and maintaining Hox profiles during spinal cord developmentSeminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 152–153:44–57.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2023.03.014

-

A Hox gene regulatory network for hindbrain segmentationCurrent Topics in Developmental Biology 139:169–203.https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2020.03.001

-

Identification of a retinoic acid response element upstream of the murine Hox-4.2 geneMolecular and Cellular Biology 13:257–265.https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.13.1.257-265.1993

-

Hox gene functions in the C. elegans nervous system: From early patterning to maintenance of neuronal identitySeminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 152–153:58–69.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2022.11.012

-

Rnf220 is implicated in the dorsoventral patterning of the hindbrain neural tube in miceFrontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 10:831365.https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.831365

-

A selective WDR5 degrader inhibits acute myeloid leukemia in patient-derived mouse modelsScience Translational Medicine 13:eabj1578.https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abj1578

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFF0702700)

- Bingyu Mao

Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202101AU070137)

- Huishan Wang

National Natural Science Foundation of China (8240055266)

- Huishan Wang

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170965)

- Pengcheng Ma

Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202205AC160065)

- Pengcheng Ma

Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202201AW070009)

- Pengcheng Ma

Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202301AS070059)

- Pengcheng Ma

Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202401AT070187)

- Huishan Wang

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all members of the Mao and Zhang laboratories for discussion of and comments on the manuscript. We would like to thank the Core Technology Facility of Kunming Institute of Zoology (KIZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) for providing us with service.

Ethics

This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All of the animals were handled according to Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Permit Number: IACUC-PA-2021-07-018). All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital or isoflurane, and every effort was made to minimize suffering.

Version history

- Sent for peer review:

- Preprint posted:

- Reviewed Preprint version 1:

- Reviewed Preprint version 2:

- Version of Record published:

Cite all versions

You can cite all versions using the DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.94657. This DOI represents all versions, and will always resolve to the latest one.

Copyright

© 2024, Wang, Liu et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 732

- views

-

- 88

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 2

- citations for Version of Record https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.94657.3