Microbiota: From bugs to beta cells

After birth, we are colonized by microbes that quickly outnumber all of the other cells in the human body. There is intense interest in how these microbes, which are collectively known as the microbiota, can promote health or contribute to disease, but comparatively little attention has been paid to their role in development. The importance of the microbiota in the development of the gut was first recognized more than 40 years ago, once it became possible to raise gnotobiotic animals (animals for which only certain known microbes are present) under germ-free conditions (Thompson and Trexler, 1971). Could the development of organs that are not in direct contact with the microbiota also be under its control?

Until recently, our understanding of the microbiota of vertebrates was limited to microbes that could be cultured in the lab. However, advances in microbial taxonomy and DNA sequencing technology have revealed enormous, and previously underappreciated, diversity in the composition and function of the microbiota (Shokralla et al., 2012). Emerging data suggests that the presence or absence of rare microbes could have profound physiological consequences: some strains can reprogram the metabolism of the entire microbial community (McNulty et al., 2011), whereas others produce factors that act directly on the host (Semova et al., 2012).

Zebrafish develop outside of the mother, which makes them an ideal vertebrate system in which to manipulate the composition of the microbiota in order to study its role in development. In addition, the optical transparency of zebrafish and the availability of many tissue-specific transgenic markers provide a window into organ development at cellular resolution. Early studies of germ-free zebrafish highlighted that the microbiota had a conserved role in the growth and maturation of the intestine (Bates et al., 2006; Rawls et al., 2004). Now, in eLife, Karen Guillemin of the University of Oregon and colleagues – Jennifer Hampton Hill (Oregon), Eric Franzosa and Curtis Huttenhower, both of Harvard and the Broad Institute – have used these tools to reveal that microbiota-host interactions could play a role in the development of beta (β) cells in the pancreas (Hill et al., 2016).

Small clusters of hormone-producing cells within the pancreas keep blood sugar levels within a narrow range. The β cells, which produce insulin, are of particular importance because they are dysfunctional in patients with diabetes (or have been destroyed). Hill, Franzosa, Huttenhower and Guillemin (who is also at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research) noticed that a rapid expansion in the number of pancreatic β cells coincided with the newly hatched zebrafish larvae being colonized by microbes. Using the germ-free system, they discovered that the microbiota is required for this expansion, which is driven by proliferation of existing β cells as well as the differentiation of new β cells (Hesselson et al., 2009).

Hill et al. then took a collection of bacterial strains that they had previously isolated from the zebrafish gut (Stephens et al., 2015), and determined which of these strains promotes β cell expansion in germ-free zebrafish. Only a subset of the strains, including several Aeromonas isolates, restored normal β cell numbers. This suggested that a strain-specific factor was involved. The Aeromonas activity was tracked to a mixture of proteins that were secreted by the strain in culture, setting off a hunt for the factor (or factors) responsible.

Using genomic and proteomic filters Hill et al. identified a single candidate protein, which they named β cell expansion factor A (BefA). When the BefA gene was deleted from the Aeromonas genome, the mutant strain still colonized germ-free zebrafish but it did not restore β cell numbers. In contrast, the addition of purified BefA protein to germ-free zebrafish fully rescued β cell development. These elegant experiments showed that BefA is necessary and sufficient to promote β cell expansion, and that it exerts its effect directly on the host. Additional experiments showed that BefA specifically promotes the proliferation of existing β cells and/or progenitor cells that are already committed to the β cell fate.

This discovery in zebrafish could have implications for human health. Homologs of BefA exist in the genomes of bacteria that colonize the human gut. Intriguingly, BefA proteins from the human microbiota also stimulated β cell expansion in zebrafish, suggesting that they share an evolutionarily conserved target. Unfortunately, the sequence of the protein does not provide many clues to its biological function.

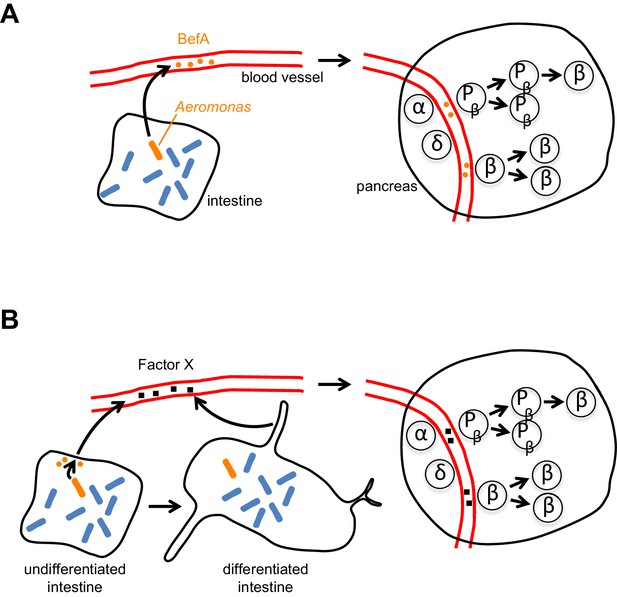

The intestines and β cells communicate extensively with each other (via hormonal and neuronal signals) to help match food intake with insulin output, and early β cell expansion could be regulated by similar inter-organ signals. Whether BefA acts directly on β cells/progenitors (Figure 1A) or indirectly by rescuing intestinal development or function in germ-free animals (Figure 1B) remains unknown. However, the gnotobiotic zebrafish system is poised to deliver fundamental insights into BefA targets and function.

How does BefA stimulate the proliferation of β cells in the pancreas?

(A) In the direct model certain microbes (such as some strains of Aeromonas, a rod-shaped bacterium shown here in orange) in the lumen of the intestine secrete BefA (orange circles), which then circulates in the blood and stimulates the proliferation of β cells and/or β cell progenitors (Pβ) in the pancreas. (B) In the indirect model BefA promotes the differentiation of the intestine or stimulates the cells lining the intestine to release an undefined ‘Factor X’ (black squares), which then circulates in the blood and promotes β cell expansion in the pancreas. The α- and δ-cells in the pancreas are not affected by BefA.

By two years of age, the proliferation of β cells in humans slows markedly (Gregg et al., 2012), which suggests that the proliferation of perinatal β cells may be important for establishing a reserve of β cells to promote lifelong metabolic health (Berger et al., 2015). Susceptible individuals with a suboptimal number of β cells may struggle to meet the increased demand for insulin associated with pregnancy or obesity. Determining whether BefA can act at later stages of development to allow β cell numbers to 'catch up' could lead to novel therapeutic approaches for the prevention of diabetes.

References

-

Formation of a human β-cell population within pancreatic islets is set early in lifeJournal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97:3197–3206.https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1206

-

The impact of a consortium of fermented milk strains on the gut microbiome of gnotobiotic mice and monozygotic twinsScience Translational Medicine 3:106ra106.https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3002701

-

Next-generation sequencing technologies for environmental DNA researchMolecular Ecology 21:1794–1805.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05538.x

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 13, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Zhang et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,256

- views

-

- 164

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

Inhibitory G alpha (GNAI or Gαi) proteins are critical for the polarized morphogenesis of sensory hair cells and for hearing. The extent and nature of their actual contributions remains unclear, however, as previous studies did not investigate all GNAI proteins and included non-physiological approaches. Pertussis toxin can downregulate functionally redundant GNAI1, GNAI2, GNAI3, and GNAO proteins, but may also induce unrelated defects. Here, we directly and systematically determine the role(s) of each individual GNAI protein in mouse auditory hair cells. GNAI2 and GNAI3 are similarly polarized at the hair cell apex with their binding partner G protein signaling modulator 2 (GPSM2), whereas GNAI1 and GNAO are not detected. In Gnai3 mutants, GNAI2 progressively fails to fully occupy the sub-cellular compartments where GNAI3 is missing. In contrast, GNAI3 can fully compensate for the loss of GNAI2 and is essential for hair bundle morphogenesis and auditory function. Simultaneous inactivation of Gnai2 and Gnai3 recapitulates for the first time two distinct types of defects only observed so far with pertussis toxin: (1) a delay or failure of the basal body to migrate off-center in prospective hair cells, and (2) a reversal in the orientation of some hair cell types. We conclude that GNAI proteins are critical for hair cells to break planar symmetry and to orient properly before GNAI2/3 regulate hair bundle morphogenesis with GPSM2.

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Developmental Biology

Organisms utilize gene regulatory networks (GRN) to make fate decisions, but the regulatory mechanisms of transcription factors (TF) in GRNs are exceedingly intricate. A longstanding question in this field is how these tangled interactions synergistically contribute to decision-making procedures. To comprehensively understand the role of regulatory logic in cell fate decisions, we constructed a logic-incorporated GRN model and examined its behavior under two distinct driving forces (noise-driven and signal-driven). Under the noise-driven mode, we distilled the relationship among fate bias, regulatory logic, and noise profile. Under the signal-driven mode, we bridged regulatory logic and progression-accuracy trade-off, and uncovered distinctive trajectories of reprogramming influenced by logic motifs. In differentiation, we characterized a special logic-dependent priming stage by the solution landscape. Finally, we applied our findings to decipher three biological instances: hematopoiesis, embryogenesis, and trans-differentiation. Orthogonal to the classical analysis of expression profile, we harnessed noise patterns to construct the GRN corresponding to fate transition. Our work presents a generalizable framework for top-down fate-decision studies and a practical approach to the taxonomy of cell fate decisions.