Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorEthel Bayer-SantosThe University of Texas at Austin, Austin, United States of America

- Senior EditorWendy GarrettHarvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Knecht, Sirias et al describe toxin-immunity pair from Proteus mirabilis. Their observations suggest that the immunity protein could protect against non-cognate effectors from the same family. They analyze these proteins by dissecting them into domains and constructing chimeras which leads them to the conclusion that the immunity can be promiscuous and that the binding of immunity is insufficient for protective activity.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well written and the data are very well presented and could be potentially interesting. The phylogenetic analysis is well done, and provides some general insights.

Weaknesses:

Conclusions are mostly supported by harsh deletions and double hybrid assays. The later assays might show binding, but this method is not resolutive enough to report the binding strength. Proteins could still bind, but the binding might be weaker, transient, and out-competed by the target binding.

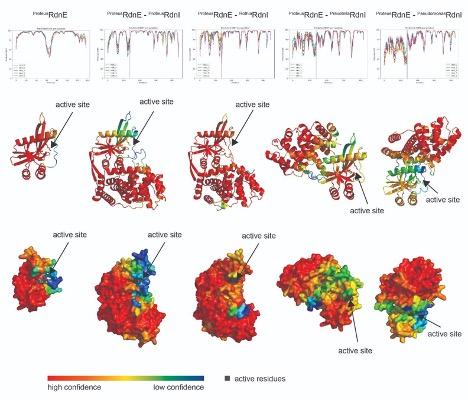

While the authors have modeled the structure of toxin and immunity, the toxin-immunity complex model is missing. Such a model allows alternative, more realistic interpretation of the presented data. Firstly, the immunity protein is predicted to bind contributing to the surface all over the sequence, except the last two alpha helices (very high confidence model, iPTM>0.8). The N terminus described by the authors contributes one of the toxin-binding surfaces, but this is not the sole binding site. Most importantly, other parts of the immunity protein are predicted to interact closer to the active site (D-E-K residues). Thus, based on the AlphaFold model, the predicted mechanism of immunization remains physically blocking the active site. However, removing the N terminal part, which contributes large interaction surface will directly impact the binding strength. Hence, the toxin-immunity co-folding model suggests that proper binding of immunity, contributed by different parts of the protein, is required to stabilize the toxin-immunity complex and to achieve complete neutralization. Alternative mechanisms of neutralization might not be necessary in this case and are difficult to imagine for a DNAse.

Dissection of a toxin into two domains is also not justified from a structural point of view, it is probably based on initial sequence analyses. The N terminus (actually previously reported as Pone domain in ref 21) is actually not a separate domain, but an integral part of the protein that is encased from both sides by the C terminal part. These parts might indeed evolve faster since they are located further from the active site and the central core of the protein. I am happy to see that the chimeric toxins are active, but regarding the conservation and neutralization, I am not surprised, that the central core of the protein fold is highly conserved. However, "deletion 2" is quite irrelevant - it deletes the central core of the protein, which is simply too drastic to draw any conclusions from such a construct - it will not fold into anything similar to an original protein, if it will fold properly at all.

Regarding the "promiscuity" there is always a limit to how similar proteins are, hence when cross-neutralization is claimed authors should always provide sequence similarities. This similarity could also be further compared in terms of the predicted interaction surface between toxin and immunity.

Overall, it looks more like a regular toxin-immunity couple, where some cross-reactions with homologues will, of course, be possible, depending on how far the sequences have deviated. Nevertheless, taking all of the above into account, these results do not challenge toxin-immunity specificity dogma.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The manuscript by Knecht et al entitled "Non-cognate immunity proteins provide broader defenses against interbacterial effectors in microbial communities" aims at characterizing a new type VI secretion system (T6SS) effector immunity pair using genetic and biochemical studies primarily focused on Proteus mirabilis and metagenomic analysis of human-derived data focused on Rothia and Prevotella sequences. The authors provide evidence that RdnE and RdnI of Proteus constitute an E-I pair and that the effector likely degrades nucleic acids. Further, they provide evidence that expression of non-cognate immunity derived from diverse species can provide protection against RdnE intoxication. Overall, this general line of investigation is underdeveloped in the T6SS field and conceptually appropriate for a broad audience journal. The paper is well-written and, aside from a few cases, well-cited. As detailed below however, there are several aspects of this paper where the evidence provided is somewhat insufficient to support the claims. Further, there are now at least two examples in the literature of non-cognate immunity providing protection against intoxication, one of which is not cited here (Bosch et al PMID 37345922 - the other being Ting et al 2018). In general therefore I think that the motivating concept here in this paper of overturning the predominant model of interbacterial effector-immunity cognate interactions is oversold and should be dialed back.

Strengths:

One of the major strengths of this paper is the combination of diverse techniques including competition assays, biochemistry, and metagenomics surveys. The metagenomic analysis in particular has great potential for understanding T6SS biology in natural communities. Finally, it is clear that much new biology remains to be discovered in the realm of T6SS effectors and immunity.

Weaknesses:

The authors have not formally shown that RdnE is delivered by the T6SS. Is it the case that there are not available genetics tools for gene deletion for the BB2000 strain? If there are genetic tools available, standard assays to demonstrate T6SS-dependency would be to interrogate function via inactivation of the T6SS (e.g. by deleting tssC).

For swarm cross-phyla competition assays (Figure 4), at what level compared to cognate immunity are the non-cognate immunity proteins being expressed? This is unclear from the methods and Figure 4 legend and should be elaborated upon. Presumably these non-cognate immunity proteins are being overexpressed. Expression level and effector-to-immunity protein stoichiometry likely matters for interpretation of function, both in vitro as well as in relevant settings in nature. It is important to assess if native expression levels of non-cognate cross-phyla immunity (e.g. Rothia and Prevotella) protect similarly as the endogenously produced cognate immunity. This experiment could be performed in several ways, for example by deleting the RdnE-I pair and complementing back the Rothia or Prevotella RdnI at the same chromosomal locus, then performing the swarm assay. Alternatively, if there are inducible expression systems available for Proteus, examination of protection under varying levels of immunity induction could be an alternate way to address this question. Western blot analysis comparing cognate to non-cognate immunity protein levels expressed in Proteus could also be important. If the authors were interested in deriving physical binding constants between E and various cognate and non-cognate I (e.g. through isothermal titration calorimetry) that would be a strong set of data to support the claims made. The co-IP data presented in supplemental Figure 6 are nice but are from E. coli cells overexpressing each protein and do not fully address the question of in vivo (in Proteus) native expression.

Lines 321-324, the authors infer differences between E and I in terms of read recruitment (greater abundance of I) to indicate the presence of orphan immunity genes in metagenomic samples (Figure 5A-D). It seems equally or perhaps more likely that there is substantial sequence divergence in E compared to the reference sequence. In fact, metagenomes analyzed were required only to have "half of the bases on reference E-I sequence receiving coverage". Variation in coverage again could reflect divergent sequence dipping below 90% identity cutoff. I recommend performing metagenomic assemblies on these samples to assess and curate the E-I sequences present in each sample and then recalculating coverage based on the exact inferred sequences from each sample.

A description of gene-level read recruitment in the methods section relating to metagenomic analysis is lacking and should be provided.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

The authors discovered that the RdnE effector possesses DNase activity, and in competition, P. mirabilis having RdnE outcompetes the null strain. Additionally, they presented evidence that the RdnI immunity protein binds to RdnE, suppressing its toxicity. Interestingly, the authors demonstrated that the RdnI homolog from a different phylum (i.e., Actinomycetota) provides cross-species protection against RdnE injected from P. mirabilis, despite the limited identity between the immunity sequences. Finally, using metagenomic data from human-associated microbiomes, the authors provided bioinformatic evidence that the rdnE/rdnI gene pair is widespread and present in individual microbiomes. Overall, the discovery of broad protection by non-cognate immunity is intriguing, although not necessarily surprising in retrospect, considering the prolonged period during which Earth was a microbial battlefield/paradise.

Strengths:

The authors presented a strong rationale in the manuscript and characterized the molecular mechanism of the RdnE effector both in vitro and in the heterologous expression model. The utilization of the bacterial two-hybrid system, along with the competition assays, to study the protective action of RdnI immunity is informative. Furthermore, the authors conducted bioinformatic analyses throughout the manuscript, examining the primary sequence, predicted structural, and metagenomic levels, which significantly underscore the significance and importance of the EI pair.

Weaknesses:

1. The interaction between RdnI and RdnE appears to be complex and requires further investigation. The manuscript's data does not conclusively explain how RdnI provides a "promiscuous" immunity function, particularly concerning the RdnI mutant/chimera derivatives. The lack of protection observed in these cases might be attributed to other factors, such as a decrease in protein expression levels or misfolding of the proteins. Additionally, the transient nature of the binding interaction could be insufficient to offer effective defenses.

2. The results from the mixed population competition lack quantitative analysis. The swarm competition assays only yield binary outcomes (Yes or No), limiting the ability to obtain more detailed insights from the data.

3. The discovery of cross-species protection is solely evident in the heterologous expression-competition model. It remains uncertain whether this is an isolated occurrence or a common characteristic of RdnI immunity proteins across various scenarios. Further investigations are necessary to determine the generality of this behavior.

Comments from Reviewing Editor:

In addition to the references provided by Reviewer #2, the first manuscript to show non-cognate binding of immunity proteins was Russell et al 2012 (PMID: 22607806).

IdrD was shown to form a subfamily of effectors in this manuscript by Hespanhol et al 2022 PMID: 36226828 that analyzed several T6SS effectors belonging to PDDExK, and it should be cited.