The fate of pyruvate dictates cell growth by modulating cellular redox potential

eLife Assessment

This fundamental work demonstrates that compartmentalized cellular metabolism is a dominant input into cell size control in a variety of mammalian cell types and in Drosophila. The authors show that increased pyruvate import into the mitochondria in liver-like cells and in primary hepatocytes drives gluconeogenesis but reduces cellular amino acid production, suppressing protein synthesis. The evidence supporting the conclusions is compelling, with a variety of genetic and pharmacologic assays rigorously testing each step of the proposed mechanism. This work will be of interest to cell biologists, physiologists, and researchers interested in cell metabolism, and is significant because stem cells and many cancers exhibit metabolic rewiring of pyruvate metabolism.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.103705.3.sa0Fundamental: Findings that substantially advance our understanding of major research questions

- Landmark

- Fundamental

- Important

- Valuable

- Useful

Compelling: Evidence that features methods, data and analyses more rigorous than the current state-of-the-art

- Exceptional

- Compelling

- Convincing

- Solid

- Incomplete

- Inadequate

During the peer-review process the editor and reviewers write an eLife Assessment that summarises the significance of the findings reported in the article (on a scale ranging from landmark to useful) and the strength of the evidence (on a scale ranging from exceptional to inadequate). Learn more about eLife Assessments

Abstract

Pyruvate occupies a central node in carbohydrate metabolism such that how it is produced and consumed can optimize a cell for energy production or biosynthetic capacity. This has been primarily studied in proliferating cells, but observations from the post-mitotic Drosophila fat body led us to hypothesize that pyruvate fate might dictate the rapid cell growth observed in this organ during development. Indeed, we demonstrate that augmented mitochondrial pyruvate import prevented cell growth in fat body cells in vivo as well as in cultured mammalian hepatocytes and human hepatocyte-derived cells in vitro. We hypothesize that this effect on cell size was caused by an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which rewired metabolism toward gluconeogenesis and suppressed the biomass-supporting glycolytic pathway. Amino acid synthesis was decreased, and the resulting loss of protein synthesis prevented cell growth. Surprisingly, this all occurred in the face of activated pro-growth signaling pathways, including mTORC1, Myc, and PI3K/Akt. These observations highlight the evolutionarily conserved role of pyruvate metabolism in setting the balance between energy extraction and biomass production in specialized post-mitotic cells.

eLife digest

Cells require nutrients to produce energy and build vital biomolecules, such as nucleic acids, proteins, lipids and carbohydrates to support organ functions. An imbalance of nutrients can significantly affect cell growth and behavior, which has been seen in diseases like cancer, diabetes and heart failure.

Pyruvate is a key product of sugar metabolism. It can enter cell components called mitochondria to fuel energy production or be converted into lactate and other molecules to support the production of essential molecules (called biosynthesis) and maintain redox balance (i.e., the right proportion of electron carriers).

The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) controls how much pyruvate enters the mitochondria, and changes in its activity have been linked to abnormal cell growth and impaired heart function. Most of our understanding of this balance comes from studies of dividing cells, but it is less clear how pyruvate affects cells that no longer divide, such as liver cells or hepatocytes in the liver.

To determine whether pyruvate metabolism directly influences biosynthetic capacity and growth of cells, Toshniwal et al. studied the fat body of fruit fly larvae, a metabolic organ analogous to the mammalian liver. The results showed that pyruvate metabolism affects cell size through changes in the redox balance of a cell.

In genetically modified cells that overexpressed MPC, more pyruvate entered the mitochondria. This restricted the growth of cells and limited protein synthesis in the fat body cells of fruit fly larvae. Restricted cell growth was also observed in spheroids derived from human liver cancer cells and in primary rat hepatocytes.

Further experiments revealed that the restricted cell growth was not the result of engaging the normal growth signaling pathways. Instead, it was due to changes in the way cells use pyruvate in the mitochondria. Rather than using it for energy production, the cells redirected it toward gluconeogenesis, producing and releasing glucose. This shift was caused by a more reduced redox state in the cell (more precisely, an imbalance in NADH/NAD+ levels).

Because of this redox shift, the cells made fewer amino acids, and with fewer building blocks for proteins, the cells could not make as much protein, limiting their growth and size.

These results demonstrate how specialized cells, such as hepatocytes, employ distinct metabolic adaptations to meet the organismal demands under varying nutritional conditions. The fate of pyruvate could profoundly influence the redox state and gluconeogenic capacity of the mammalian liver. Understanding these mechanisms may eventually benefit patients with metabolic disorders, such as diabetes. Until then, further studies are needed to translate these findings from model systems to human physiology and to evaluate the safety and efficacy of targeting these pathways in living organisms.

Introduction

Cells must appropriately allocate available nutrients to optimize their metabolic programs—for energy extraction and for the generation of building blocks that enable cell growth. The balance between these processes not only maintains cellular health under varying nutritional conditions but also plays an important role in determining cell fate and function (Baker and Rutter, 2023; DeBerardinis and Thompson, 2012; Ghosh-Choudhary et al., 2020; Metallo and Vander Heiden, 2013). For example, hepatocyte metabolism changes considerably between fed and fasted conditions. In the fed state, hepatocytes use the majority of their nutrients to synthesize proteins, lipids, and glycogen, which results in increased cell size and liver biomass (Kast et al., 1988; Reinke and Asher, 2018; Sinturel et al., 2017). To meet the energy demands of other tissues during fasting, the liver undergoes a metabolic shift to produce glucose from biosynthetic precursors, thereby decreasing hepatocyte and liver size (Lang et al., 1998; Sinturel et al., 2017).

The metabolic pathways that support biosynthetic metabolism can be inappropriately activated in diseases such as cancer and heart failure to promote pathological growth. For example, many of the primary oncogenic adaptations in tumors prioritize anabolic metabolism over ATP production, which facilitates rapid cell proliferation (Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Vander Heiden et al., 2009; Zhu and Thompson, 2019). Metabolic rewiring during heart failure similarly results in greater biosynthetic potential and less efficient ATP production, which in post-mitotic cardiomyocytes leads to increased cell size and insufficient cardiac pumping (Bornstein et al., 2024; Henry et al., 2024; Weiss et al., 2023).

The fate of pyruvate, which is primarily generated from glucose via glycolysis in the cytoplasm, is a critical node that can determine the balance between energetic and biosynthetic metabolism (Baker and Rutter, 2023; Yiew and Finck, 2022). In most differentiated cells, the majority of pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria via the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) complex, a heterodimer composed of MPC1 and MPC2 proteins (Bricker et al., 2012; Herzig et al., 2012). Once in the mitochondria, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH), fueling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and supporting efficient ATP production. In cancer, stem, and other proliferative cells, more pyruvate is converted to lactate and exported from the cell, a process that regenerates NAD+, a cofactor necessary for glycolytic flux (Baker and Rutter, 2023; Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Zhu and Thompson, 2019). In some specialized cells, including hepatocytes, pyruvate is imported into mitochondria but converted to oxaloacetate, which can feed the TCA cycle but also serves as a precursor for glucose production via gluconeogenesis (Holeček, 2023b; Jitrapakdee et al., 2008). We and others have demonstrated that these alternative fates of pyruvate—energy generation, cell proliferation, or glucose production—differentially impact the metabolic and fate decisions of multiple cell types in varying contexts (Bensard et al., 2020; Cluntun et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2022; Yiew and Finck, 2022). Loss of MPC function, which shifts pyruvate metabolism toward lactate production and thus expedites glycolysis and the production of biosynthetic precursors, has been shown to increase cell proliferation in mouse and Drosophila intestinal stem cells as well as in various tumors (Bensard et al., 2020; Schell et al., 2017; Zangari et al., 2020). MPC expression is also reduced in human and mouse models of heart failure, and genetic deletion of the MPC in cardiomyocytes is sufficient to induce hypertrophy and heart failure (Cluntun et al., 2021; Fernandez-Caggiano et al., 2020; McCommis et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Conversely, MPC overactivation or overexpression restricts intestinal stem cell proliferation and limits the growth of cardiomyocytes under hypertrophic stimuli, with excess mitochondrial pyruvate fueling the TCA cycle (Bensard et al., 2020; Schell et al., 2014; Schell et al., 2017). These observations suggest that mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism is central to cell proliferation as well as the size and specialized functions of post-mitotic cells.

The mechanisms regulating cell size include well-characterized cellular signaling pathways and transcriptional programs (Grewal, 2009; Liu et al., 2022; Lloyd, 2013). The CDK4–Rb pathway monitors cell size in proliferating cells by coupling cell growth with cell division (Amodeo and Skotheim, 2016; Ginzberg et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). In response to insulin and other growth factors, the PI3K/Akt pathway activates mTORC1, leading to increased biosynthesis of proteins, lipids, and nucleotides, and consequently, increased cell size (Gonzalez and Rallis, 2017; Gonzalez and Rallis, 2017; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). The pro-growth transcription factor Myc drives a gene expression program that enhances metabolic activity and protein synthesis, resulting in larger cells (Baena et al., 2005; Dang, 1999; Iritani and Eisenman, 1999; Stine et al., 2015; van Riggelen et al., 2010). However, we only partially understand how metabolic pathways regulate physiological (or pathophysiological) growth, particularly in cells that have distinct and specialized roles in organismal metabolism.

Here, we investigated whether pyruvate metabolism influences biosynthetic capacity and cell size, using the Drosophila fat body as a model of the mammalian liver. We found that MPC overexpression and increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport restrict cell growth and limit protein synthesis in larval fat body cells and in spheroids of human liver-derived cells. Higher MPC expression resulted in smaller cells, not by increasing TCA cycle flux as observed in other cell types, but instead by redirecting mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism toward gluconeogenesis. A key driver of this metabolic rewiring is a reduced cellular redox state, which disrupts the biosynthesis of TCA cycle-derived amino acids, such as aspartate and glutamate, ultimately reducing protein synthesis. These observations highlight how cells with specialized functions, like hepatocytes, employ distinct metabolic adaptations to respond to organismal demands under varying nutritional conditions.

Results

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport reduces the size of Drosophila fat body cells

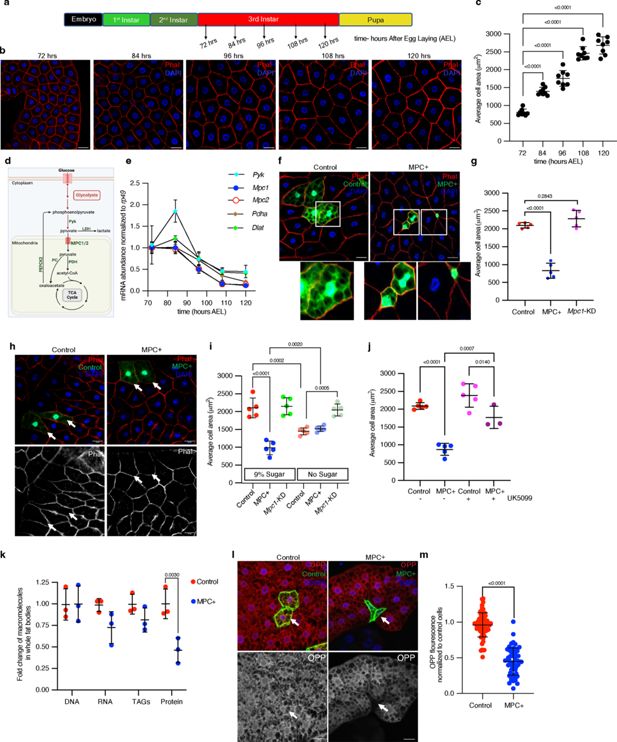

The Drosophila fat body is functionally analogous to mammalian white adipose tissue and liver, serving as a buffer to store excess nutrients in fat droplets and glycogen and deploy them to support the animal with fuel during times of fasting (Arrese and Soulages, 2010; Musselman et al., 2013). During larval development, fat body cells halt cell division and dramatically increase in size during the third instar stage (from 72 to 120 hr After Egg Laying (AEL)) (Edgar and Orr-Weaver, 2001; Zheng et al., 2016; Figure 1a–c). As a first step toward understanding the metabolic programs that enable this rapid cell growth, we performed RNA sequencing of the Drosophila fat body across this developmental period. We observed a time-dependent change in mRNAs encoding proteins that have well-characterized roles in supporting cell growth, including components of the insulin and mTORC1 signaling pathways and the Myc transcriptional network, which correlated with increased cell size (Figure 1—figure supplement 1a). Among metabolic genes, we observed modest differences in those that function in amino acid synthesis and fatty acid metabolism (Figure 1—figure supplement 1b). The abundances of mRNAs encoding proteins involved in glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos), and the TCA cycle were distinctly altered in fat bodies during development (Figure 1—figure supplement 1b). Since pyruvate metabolism is the central node connecting carbohydrate metabolism and the TCA cycle, we studied the abundances of mRNAs that encode proteins that regulate pyruvate metabolism (Figure 1d). We found that the expression of genes that link pyruvate to the TCA cycle was reduced, including Pyk, the Drosophila pyruvate kinase homolog, which converts phosphoenolpyruvate into pyruvate. Mpc1 and Mpc2, which encode the two subunits of the MPC, which transports pyruvate into the mitochondrial matrix; as well as Pdha and Dlat, which encode subunits of PDH complex (Figure 1e). In contrast, some mRNAs encoding proteins that regulate pyruvate abundance were upregulated, such as Pepck and Pepck2, which make phosphoenolpyruvate from oxaloacetate (Figure 1—figure supplement 1c). Based on these data, we hypothesized that the suppression of mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism, which is gated by the action of the MPC, might support the rapid cell growth observed in fat body cells.

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport reduces size of Drosophila fat body cells.

(a) A schematic representation of Drosophila developmental stages with specified time points (hours after egg laying (AEL) at 25°C) at which larvae were dissected to collect fat bodies. (b) Representative images of larval fat bodies at the indicated times (hours AEL) stained with rhodamine phalloidin to visualize cell membranes and DAPI to visualize DNA. The scale bar represents 25 μm. (c) Quantification of fat body cell area based on rhodamine phalloidin stained cell membranes at the indicated time points. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) from six biological replicates, with each replicate averaging the size of 50 randomly selected cells from fat bodies dissected from five male larvae. (d) A schematic of pyruvate metabolism. In the cytoplasm, pyruvate is a product of glycolysis, synthesized by pyruvate kinase (Pyk) or from lactate via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Pyruvate is transported into mitochondria by the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) complex. Within mitochondria, pyruvate is converted into acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) or into oxaloacetate by pyruvate carboxylase (PC), both of which are substrates for the TCA cycle. PEPCK2 converts oxaloacetate into phosphoenolpyruvate. (e) Pyk, Mpc1, Mpc2, Pdha, and Dlat transcripts were quantified from larval fat bodies collected at the indicated times. (f) Representative confocal microscope images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat bodies with flip-out Gal4 clones expressing MPC1-P2A-MPC2 (MPC+), marked with GFP at 120 hr AEL. The images at the bottom show magnified insets of GFP-positive cells in control and MPC-expressing clones. (g) Quantification of GFP-positive clonal cell area with the indicated genetic manipulations—control, MPC+, and Mpc1-KD. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from six biological replicates, with each set averaging the size of 20 clonal cells from fat bodies collected from five male larvae. (h) Images showing control and MPC+ clones from larvae fed on no sugar diet. (i) Quantification of the area of control, MPC+ and Mpc1-KD fat body clonal cells from larvae fed on a diet containing either 9% sugar or no sugar. (j) Quantification of the area of MPC+ fat body clonal cells from larvae fed a diet supplemented with or without 20 μM UK5099. (k) Fold change of the abundances of the indicated macromolecules in fat bodies expressing MPC (MPC+) in all fat body cells using CG-Gal4. The abundance of each individual macromolecule is normalized to that of the respective macromolecular abundance in GFP-expressing, control fat bodies. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. from three biological replicates with fat bodies collected from 10 larvae at 120 hr AEL. (l) Representative images of fat body clones stained with O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP, 20 μM for 30 min), showing control and MPC expressing GFP-positive cells. The top panels show GFP-positive clones and OPP staining in red, while the bottom panels show respective OPP channel. Arrows indicate cells with the specified genetic manipulation. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (m) Quantification of OPP fluorescence intensity of control or MPC+ fat body cells compared to neighboring non-clonal cells. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from six biological replicates, with each set averaging the size of 20 clonal cells from fat bodies collected from five male larvae. Unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the data, with p-values mentioned in the graphs where significance was noted. Panel d was created with BioRender.com.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

To test this hypothesis, we prevented the downregulation of the MPC during larval development (Figure 1e) by ectopically expressing Mpc1 and Mpc2 (termed ‘MPC+’ Figure 1—figure supplement 2a and b). The sustained expression of the MPC (both Mpc1 and Mpc2) throughout the fat body significantly reduced the rate of cell growth compared to a GFP-expressing control (Figure 1—figure supplement 2c). Given the important role of the fat body in controlling organismal growth, we wanted to assess the cell-autonomous effects of MPC expression using mosaic analysis in individual fat body cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 2d; Ito et al., 1997). We generated GFP-labeled clones with expression of the MPC (MPC+), which we confirmed by immunofluorescence (Figure 1—figure supplement 2e, f). The MPC-expressing, GFP-positive cells were significantly smaller in size compared with either mock clones (control) or neighboring GFP-negative cells within the same tissue. Mpc1 knockdown (Mpc1-KD) clones, in contrast, were marginally larger (Figure 1f, g). These results demonstrate that sustained expression of the MPC in developing fat body cells is sufficient to prevent cell growth in a cell-autonomous manner.

If the effects of MPC expression were related to the mitochondrial transport of pyruvate, then limiting the production of pyruvate should mitigate these effects. Therefore, we measured cell size in larvae raised on either a normal (9% sugar) diet or a diet with no added sugars, which limits the production of pyruvate from glucose and fructose. Limiting dietary sugars significantly reduced the size of control clones but increased the size of MPC-expressing clones. Notably, the size of MPC-expressing fat body clones was comparable to that of control clones when larvae were grown in sugar-limited medium, suggesting that limiting pyruvate synthesis abolishes the effect of MPC expression on fat body cell size (Figure 1h, i). Mpc1-KD clones were again larger than control cells, and their size was unaffected by the sugar-limited diet. Inhibiting MPC activity by feeding larvae a normal diet supplemented with the MPC inhibitor UK5099 ameliorated the cell size effects of MPC expression (Figure 1j; Figure 1—figure supplement 2g). These results indicate that pyruvate transport into mitochondria inversely correlates with the size gain in fat body cells. These observations also suggest that the suppression of mitochondrial pyruvate import and metabolism is required for the rapid cell size expansion observed in the fat body during larval development.

The size of a cell is determined by its content of proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids (Björklund, 2019; Lloyd, 2013; Schmoller and Skotheim, 2015). To understand how MPC expression affects the abundance of these macromolecules, we dissected fat bodies from control and fat body-wide MPC-expressing larvae at 120 hr AEL and quantified DNA, RNA, triacylglycerides, and protein. Control and MPC+ fat bodies had equivalent DNA content (Figure 1k; Figure 1—figure supplement 2h) and similar levels of EdU incorporation (Figure 1—figure supplement 2o, p), suggesting that MPC expression does not impact DNA endoreplication. RNA and lipid content were modestly decreased in MPC+ fat bodies compared with control tissues (Figure 1k; Figure 1—figure supplement 2i, j), although the number of lipid droplets was higher with MPC expression (Figure 1—figure supplement 2l–n). In contrast, MPC expression dramatically decreased protein abundance in fat bodies (Figure 1k, Figure 1—figure supplement 2k), and reduced protein synthesis as assessed by staining for the puromycin analog, O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) (Deliu et al., 2017; Villalobos-Cantor et al., 2023; Figure 1l and m). These data suggest that MPC-mediated mitochondrial pyruvate import decreases protein synthesis, which likely contributes to the reduced size of MPC-expressing cells. Conversely, in developing fly larvae, repression of the MPC and the subsequent decrease in mitochondrial pyruvate appear to provide a metabolic mechanism to support a rapid expansion in cell size.

Growth factor signaling pathways are hyperactivated in MPC-expressing cells

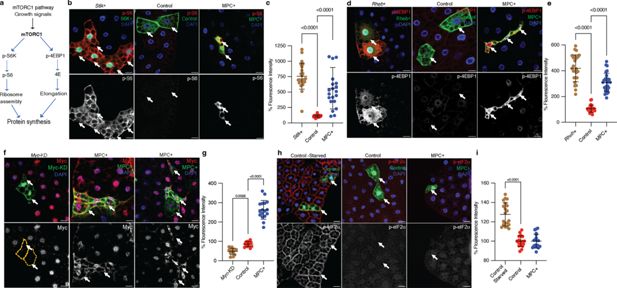

The best understood mechanisms that govern cell size involve conserved signaling and transcriptional networks (Björklund, 2019; Grewal, 2009; Lang et al., 1998; Lloyd, 2013). For example, the mTORC1 pathway coordinates both extracellular and intracellular growth regulatory signals to dictate the synthesis and degradation of macromolecules, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (Gonzalez and Rallis, 2017; Gonzalez and Rallis, 2017; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). mTORC1 increases protein synthesis through the phosphorylation of several proteins, including S6 kinase (S6K) and 4EBP1 (Figure 2a). Since MPC-expressing clones were smaller in size and had reduced protein synthesis compared with control clones, we assessed mTORC1 activity in the fat body using our mosaic expression system. As a control, we confirmed that S6k (the Drosophila gene encoding S6K) over-expressing clones were larger in size and had elevated phospho-S6 staining compared with wild-type clones (Figure 2b and c). Surprisingly, MPC+ clones also had elevated phospho-S6 staining (Figure 2b, c), suggesting that despite their small size, these cells have high mTORC1 activity. Overexpression of Rheb, which is an upstream activator of mTORC1, resulted in clones that were larger than wild-type controls and which had increased phospho-4EBP1 staining (Figure 2d, e). Again, even though the MPC+ clones were smaller in size, we observed robust p-4EBP1 staining, indicating that mTORC1 is hyperactive in these cells.

mTORC1 and Myc pathways are hyperactivated in MPC expressing fat body cells.

(a) Schematic of the mTORC1 pathway. The mTORC1 pathway is activated by pro-growth signals such as insulin, leading to the phosphorylation of S6 kinase (S6K) and 4EBP. S6K phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6, while 4EBP phosphorylation inactivates 4EBP and releases elongation factor eIF4E. These events increase ribosomal assembly and elongation rates, thereby enhancing protein synthesis. (b) Representative images of fat body clones with S6k overexpression, control clones, and MPC+ clones, stained for phosphorylated S6 (p-S6) in red (top panels) and white (bottom panels). Arrows indicate clonal cells with the specified genetic manipulation. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (c) Quantification of total p-S6 fluorescence intensity in GFP-positive cells compared to neighboring GFP-negative cells in MPC+ versus control clones. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. with statistical significance as scored with one-way ANOVA test. (d) Representative images of fat body clones with Rheb over-expression, control clones, and MPC+ clones stained for phosphorylated 4EBP (p-4EBP) in red (top panels) and white (bottom panels). Arrows indicate clonal cells with the specified genetic manipulation. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (e) Quantification of total p-4EBP fluorescence intensity in MPC+ versus control clones with statistical significance as scored with One-way ANOVA test. (f) Representative images of fat body clones with Myc knockdown, control clones, and MPC+ clones stained for Myc protein in red (top panels) and white (bottom panels). Arrows indicate clonal cells with the specified genetic manipulation. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (g) Quantification of total Myc fluorescence intensity in MPC+ versus control clones with statistical significance as scored with one-way ANOVA test. (h) Representative images of fat body clones from starved wild type, control clones, and MPC+ clones, stained for phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) in red (top panels) and white (bottom panels). Arrows indicate clonal cells with the specified genetic manipulation. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (i) Quantification of total p-eIF2α fluorescence intensity in MPC+ versus control clones with statistical significance as scored with one-way ANOVA test. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. One-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the data, with p-values noted in the graph if significance was observed.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig2-data1-v1.xlsx

Gene set enrichment analysis of RNA-sequencing data from MPC-expressing fat bodies showed enrichment for signatures associated with pro-growth signaling (Figure 2—figure supplement 1a). We assessed markers of several of these pathways in MPC+ clones. In addition to the mTORC1 pathway, Myc increases cell growth by regulating the transcription of ribosome subunits and biosynthetic metabolic genes. We found that MPC+ clones had an elevated abundance of the Myc protein, both in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 2f, g), suggesting that the growth-promoting Myc transcriptional program is active in these cells. MPC+ clones also had reduced expression of the transcription factor Foxo, consistent with its downregulation by pro-growth signaling pathways (Figure 2—figure supplement 1b). Finally, we stained for phospho-eIF2α to assess the activity of the integrated stress response, which restricts global protein synthesis. Starvation robustly induced the integrated stress response in control clones, but MPC+ clones exhibited no evidence of activation of this pathway under normal growth conditions (Figure 2h, i). Collectively, these data indicate that conventional pro-growth pathways are activated in MPC-expressing clones, which is incongruent with the small size of the clones. This suggests that mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism controls cell size via alternative molecular mechanisms.

We next performed genetic epistasis analysis to better understand the relationship between MPC expression and the mTORC1, PI3K, and Myc pathways. Activation of the PI3K or mTORC1 pathways, via overexpression of PI3K, increased the size of control but not MPC-expressing fat body cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 1c). Similarly, activation of mTORC1 via knockdown of its inhibitor, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 (Tsc1), increased the size of control cells but had no effect on MPC+ cell size (Figure 2—figure supplement 1d). Overexpression of Myc, on the other hand, increased the size of control and MPC+ fat body clones to a similar degree (Figure 2—figure supplement 1e). Knockdown of Myc was sufficient to decrease cell size to a similar extent as MPC expression; however, Myc knockdown had no additional effect on cell size in MPC+ clones (Figure 2—figure supplement 1f). These results suggest that neither mTORC1, PI3K, nor Myc is epistatic to MPC and suggest that MPC likely acts independently of these canonical pathways to regulate the size of fat body cells.

We next performed genetic epistasis analysis to better understand the relationship between MPC expression and the mTORC1, PI3K, and Myc pathways. Activation of the PI3K or mTORC1 pathways, via overexpression of PI3K, increased the size of control but not MPC-expressing fat body cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 1c). Similarly, activation of mTORC1 via knockdown of its inhibitor, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 (Tsc1), increased the size of control cells but had no effect on MPC+ cell size (Figure 2—figure supplement 1d). Overexpression of Myc, on the other hand, increased the size of control and MPC+ fat body clones to a similar degree (Figure 2—figure supplement 1e). Knockdown of Myc was sufficient to decrease cell size to a similar extent as MPC expression; however, Myc knockdown had no additional effect on cell size in MPC+ clones (Figure 2—figure supplement 1f). These results suggest that neither mTORC1, PI3K, nor Myc is epistatic to MPC and suggest that MPC likely acts independently of these canonical pathways to regulate the size of fat body cells.

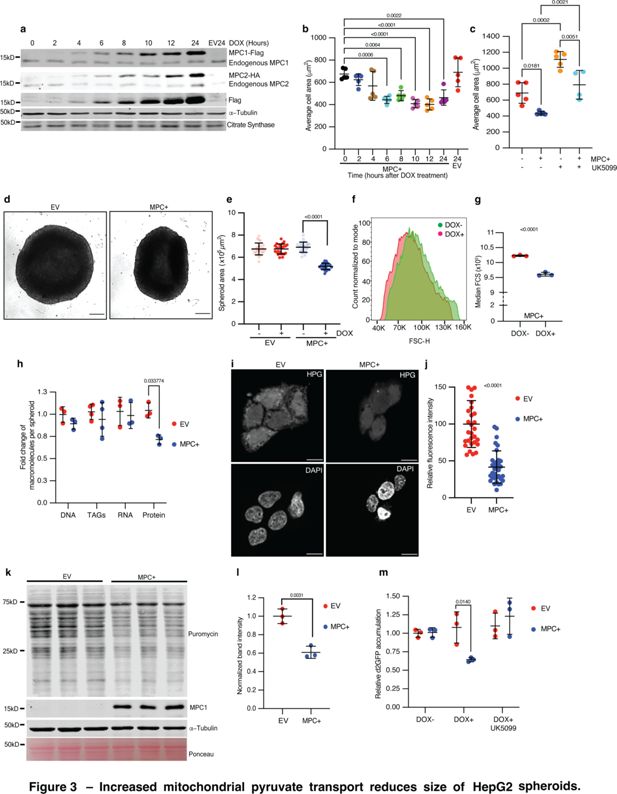

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport reduces the size of HepG2 cells and spheroids

Since the Drosophila fat body has many features reminiscent of the mammalian liver, we tested whether MPC expression might similarly restrict cell size in cells derived from this tissue. We engineered HepG2 cells, which were originally isolated from a hepatocellular carcinoma, to express epitope-tagged MPC1 and MPC2 in a doxycycline-inducible manner. We observed expression of ectopic MPC1 and MPC2 starting at 4 hr after doxycycline treatment, which increased over the duration of the time course, peaking at 24 hr post-induction (Figure 3a). We stained doxycycline-treated cells with phalloidin and measured cell size using microscopy images taken at 2-hr intervals. Induction of MPC expression coincided with a significant reduction in cell size, which was first apparent 6 hr post-doxycycline treatment and was sustained for the remainder of the time course (Figure 3b). Doxycycline had no effect on the size of control HepG2 cells (EV). Treatment with the MPC inhibitor UK5099 for 24 hr markedly increased the size of control cells and partially reversed the small size phenotype of MPC-expressing cells (Figure 3c). We also assessed cell volume by analyzing a 3D reconstruction of confocal images of phalloidin-stained HepG2 cells and found that the cell volume was lower in MPC+ cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1a).

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport reduces size of HepG2 spheroids.

(a) Western blots showing inducible expression of MPC1 and MPC2 at 2-hr intervals following treatment with 1 μg/ml doxycycline. Citrate synthase and tubulin were used as loading controls. Both endogenous and epitope tag bands are shown. (b) Quantification of the 2D area of HepG2 cells with MPC expression (MPC+) or empty vector (EV) fixed and stained with rhodamine phalloidin at the indicated times after doxycycline treatment. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from five biological replicates, with each replicate representing the average size of 25 randomly selected cells. (c) Quantification of the 2D area of MPC+ or EV HepG2 cells treated with 10 μM UK5099. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from five biological replicates, with each replicate representing the average size of 25 randomly selected cells. (d) Representative brightfield images of HepG2 spheroids with empty vector (EV) or MPC expression (MPC+) treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 6 days. The scale bar represents 200 μm. (e) Quantification of spheroid area from images of MPC+ or EV HepG2 spheroids, with or without doxycycline treatment. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from 30 technical replicates. (f) Forward scatter (FSC) of cells dissociated from MPC+ (red) or EV spheroids with cell count normalized to mode. (g) Median FSC of MPC+ HepG2 spheroids treated with or without 1 μg/ml doxycycline. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three biological replicates. (h) Fold change in macromolecules—DNA, TAGs, RNA, and protein—fractionated from EV or MPC+ HepG2 spheroids normalized to that in EV HepG2 cells. (i) Representative images showing L-homopropargylglycine (HPG)-labeled newly synthesized proteins in EV or MPC+ HepG2 cells. The top panels show HPG staining, and the lower panels show nuclei stained with DAPI. The scale bar represents 20 μm. (j) Quantification of HPG fluorescence intensity is presented as mean ± s.d. from 35 cells, for both EV and MPC+ cells. (k) Western blot analysis of nascent protein synthesis using a puromycin incorporation assay (20 μg/ml puromycin for 30 min) in either EV or MPC+ HepG2 spheroids (protein lysates from 16 spheroids loaded in each lane). (l) Quantification of 70 kD band intensity in puromycin blot normalized with tubulin band intensity and represented as mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments. (m) Relative accumulation of destabilized GFP (d2GFP) in EV or MPC+ HepG2 spheroids treated with or without 1 μg/ml doxycycline ± 10 μM UK5099. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three biological replicates. Unpaired t-tests, one-way, or two-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the data, with p-values noted in the graph if significance was observed.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig3-data1-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 3a.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig3-data2-v1.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 3

PDF files containing original western blots for Figure 3a, indicating the relevant bands and treatments.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig3-data3-v1.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 4

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 3k.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig3-data4-v1.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 5

PDF files containing original western blots for Figure 3k, indicating the relevant bands and treatments.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig3-data5-v1.zip

We have observed that the physiological consequences of altered pyruvate metabolism are more apparent in cells grown in a three-dimensional culture environment (Schell et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2022). Using our doxycycline-inducible cells, we found that MPC expression resulted in spheroids that were significantly smaller than control spheroids as assessed by microscopy (Figure 3d, e). Cells from MPC-expressing spheroids were also smaller, as shown by flow cytometry (Figure 3f, g). When compared with control (EV) spheroids, expression of MPC did not affect the number of cells per spheroid, the cell cycle phase distribution, or the number of apoptotic or necrotic cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1b-d). These analyses suggest that the smaller size observed in MPC-expressing spheroids is not due to effects on cell proliferation or cell death.

Consistent with our observations in the Drosophila fat body, protein content was lower in MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids compared with EV controls, whereas there was no difference in the abundances of DNA, RNA, or triacylglycerides (Figure 3h; Figure 3—figure supplement 1e-h). To directly assess the effect of MPC expression on protein synthesis, we induced the MPC in HepG2 cells and treated the cells acutely with a low concentration of puromycin to label nascent proteins. We found that MPC expression decreased the incorporation of the amino acid analog L-homopropargylglycine (HPG) (Shen et al., 2021; Tom Dieck et al., 2012) into nascent proteins, as assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3i, j). Protein synthesis was similarly reduced in MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids (Figure 3k, l). These observations were further supported by the decreased abundance of the short-lived, destabilized GFP (d2GFP) (Li et al., 1998; Pavlova et al., 2020) in MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids compared with controls (Figure 3m). This reduction in the level of d2GFP was prevented by treatment with the MPC inhibitor UK5099 (Figure 3m). Together, these data suggest that increased transport of pyruvate into mitochondria, mediated by MPC expression, reduces protein synthesis and cell size in both fly and mammalian models.

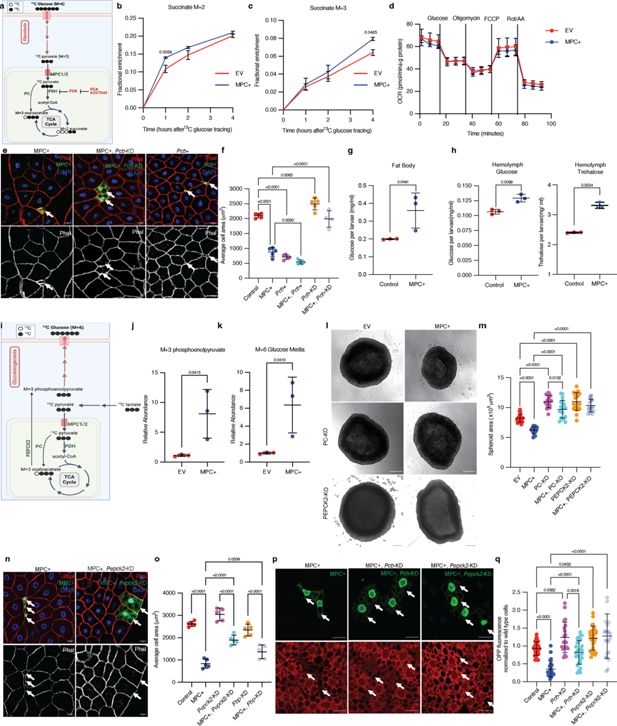

Excess mitochondrial pyruvate promotes gluconeogenesis

We have previously shown that loss of the MPC reduces the contribution of glucose and pyruvate to the TCA cycle (Bensard et al., 2020; Cluntun et al., 2021). To investigate how MPC expression impacts carbohydrate metabolism in HepG2 cells, we performed metabolic tracing using 13C-glucose (Figure 4a). We observed that MPC expression reduced the labeling fraction of the glycolytic intermediates 3-phosphoglycerate (Figure 4—figure supplement 1a) and pyruvate (Figure 4—figure supplement 1b), as well as alanine (Figure 4—figure supplement 1c), which is derived from pyruvate, all of which suggests a reduction in glycolysis in these cells. Once imported into mitochondria, glycolytic-derived pyruvate has two major fates: conversion to acetyl-CoA by PDH or to oxaloacetate by pyruvate carboxylase (PC). These fates can be differentiated by assessing the abundances of M+2 (derived from PDH) and M+3 (derived from PC) TCA cycle intermediates (Figure 4a). We found that both M+2 and M+3 isotopomers of TCA cycle intermediates were modestly increased following MPC expression (Figure 4b and c; Figure 4—figure supplement 1d–i). The fact that we observe increases in TCA cycle intermediates despite decreased glycolytic labeling in pyruvate suggests that the apparent labeling through PDH and PC might be underestimating the effect on metabolic flux through these enzymes. Thus, it appears that MPC expression increases the activity of both enzymes that utilize pyruvate. Typically, when TCA cycle flux is increased, one observes an increase in activity of the electron transport chain (ETC) to oxidize the resulting NADH. However, MPC expression had no impact on ETC activity as assessed by measuring oxygen consumption (Figure 4d). The implications of elevated NADH production without a concomitant increase in NADH oxidation will be discussed in Figure 5.

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism promotes gluconeogenesis via pyruvate carboxylase to suppress protein synthesis.

(a) Schematic illustration of the 13C-glucose tracing strategy used to measure the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and pyruvate carboxylase (PC). TCA metabolites labeled with two heavy carbons (13C or M+2 TCA pool) result from PDH activity, whereas M+3 TCA metabolites result from PC activity. PDH is inhibited by PDK-mediated phosphorylation. DCA and AZD7545 are inhibitors of PDK. (b) Fractional enrichment of M+2 succinate in empty vector (EV; red) and MPC-expressing (MPC+; blue) HepG2 cells at the indicated times after 13C-glucose tracing. MPC expression was induced for 24 hr by treatment with 1 µg/ml doxycycline and media was changed to 12C-glucose. The change in M+2 succinate is significant (by two-way ANOVA test) at 1 hr after 13C glucose incubation. (c) Fractional enrichment of M+3 succinate in EV (red) and MPC+ (blue) HepG2 at the indicated times after 13C-glucose tracing. MPC expression was induced for 24 hr by treatment with 1 μg/ml doxycycline. The change in M+3 succinate is significant (by two-way ANOVA test) at 4 hr after 13C-glucose incubation. (d) Rate of oxygen consumption (OCR) in EV and MPC+ HepG2 cells. (e) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat body cells. Arrows indicate GFP-positive clones with MPC expression (MPC+), Pcb knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Pcb-KD), or Pcb overexpression (Pcb+). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (f) Quantification of the area of GFP-positive clones with control, MPC+, Pcb over-expression (Pcb+), Pcb and MPC co-expression (MPC+, Pcb+), Pcb knockdown (Pcb-KD), and Pcb knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Pcb-KD) shown as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with each group representing the analysis of 20 the indicated clonal cells. Concentration of glucose in the fat body (g) and concentration of glucose and trehalose in hemolymph (h) of larva with fat body-specific expression MPC or control. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates analyzed by unpaired t-tests. (i) Schematic illustration of the strategy to analyze gluconeogenesis from 13C-lactate. Cells convert 13C-lactate into 13C-pyruvate, which is transported into mitochondria by the MPC. PC converts 13C-pyruvate (M+3) into oxaloacetate (M+3). PEPCK2 converts oxaloacetate (M+3) into phosphoenolpyruvate (M+3), which is converted into M+6 glucose and excreted from cells. (j) Relative abundances of M+3 phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) in EV and MPC+ HepG2 cells and (k) M+6 glucose in their respective media following treatment with 20 mM 13C-lactate for 4 hr. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates, each with an average of three technical replicates. (l) Representative brightfield images of EV, MPC+, and PC knockout (KO) or PEPCK2 KO with or without MPC expression HepG2 spheroids. The scale bar represents 200 µm. (m) Quantification of spheroid area is presented as mean ± s.d. of 30 technical replicates. (n) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat body cells. Arrows indicate GFP-positive clones with MPC expression (MPC+), and Pepck2 knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Pepck2-KD). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (o) Quantification of the area of GFP-positive clones with MPC+, Pepck2 knockdown (Pepck2-KD), Pepck2 knockdown with MPC+ (MPC+, Pepck2-KD), Fbp knockdown (Fbp-KD), Fbp knockdown with MPC+ (MPC+, Fbp-KD). Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with each group analyzing 20 clonal cells of the mentioned genetic manipulations. (p) Representative images of fat body clones stained with OPP (red). Arrows indicate GFP-positive clones with MPC expression (MPC+), Pcb knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Pcb-KD), or Pepck2 knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Pepck2-KD). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (q) Quantification of OPP intensity in the indicated clones compared with adjacent wild-type cells. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. Unpaired t-tests, one-way ANOVA tests, or two-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the data, with p-values mentioned in the graph if significance is noted. Panel a was created with BioRender.com. Panel i was created with BioRender.com.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig4-data1-v1.xlsx

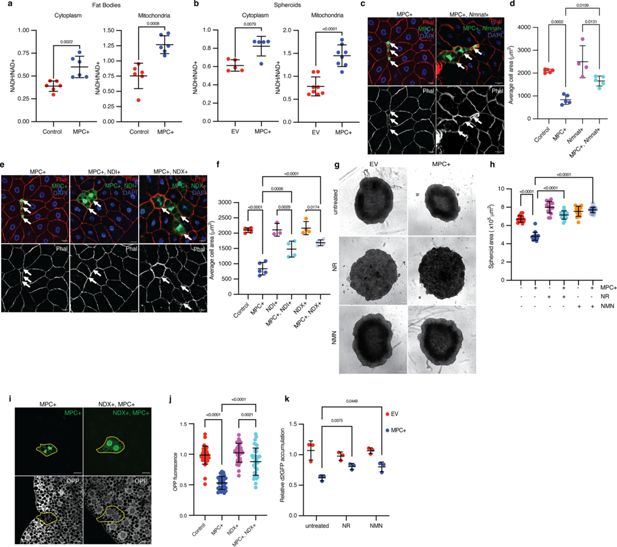

Redox imbalance impedes protein synthesis and cell growth from elevated pyruvate metabolism in mitochondria.

(a) NADH/NAD+ ratios from the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions of control and MPC-expressing (MPC+) fat bodies. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of six biological replicates. (b) NADH/NAD+ ratios from the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions of empty vector (EV) and MPC-expressing (MPC+) HepG2 spheroids. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of six biological replicates. (c) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat bodies. Arrows indicate GFP-positive cells with either MPC+ or MPC and Nmnat co-expression (MPC+, Nmnat+). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (d) Quantification of the areas of GFP-positive cells with control, MPC+, Nmnat overexpression (Nmnat+), MPC and Nmnat co-expression (MPC+, Nmnat+). Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with 20 clonal cells analyzed for each of the indicated genetic manipulations. (e) Representative images of Phalloidin and DAPI-stained fat body tissues. Arrows indicate GFP-positive cells showing MPC expression (MPC+); NDI and MPC expression (MPC+, NDI+); and NDX and MPC expression (MPC+, NDX+). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (f) Quantification of the area of GFP-positive cells with control, MPC+, NDI expression (NDI+), NDI and MPC expression (MPC+, NDI+), NDX expression (NDX+), NDX and MPC co-expression (MPC+, NDX+). Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with 20 clonal cells analyzed for each of the indicated genetic manipulations. (g) Representative bright field images of EV or MPC+HepG2 spheroids cultured with NAD+ supplements (100 nM nicotinamide riboside or 1 µM NMN) as indicated. The scale bar represents 200 µm. (h) Quantification of spheroid area is presented as mean ± s.d. of 30 technical replicates. (i) Representative images MPC+ or MPC+, NDI+ GFP-positive clones and of fat body cells stained with OPP (bottom). Clonal cells are mapped with dotted lines. The scale bar represents 20 µm. (j) Fold change in OPP intensity of 35 GFP-positive cells compared with adjacent wild-type cells. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. (k) Relative accumulation of destabilized GFP (d2GFP) in spheroids of EV or MPC+ HepG2 cells treated with NAD+ supplements (100 nM nicotinamide riboside or 1 µM NMN) as indicated. Unpaired t-tests, one-way ANOVA tests, or two-way ANOVA tests were performed to assess the statistical significance of the data, with p-values indicated in the graph where significance was observed.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig5-data1-v1.xlsx

To probe the impact of increased flux through the PC and PDH reactions, we conducted genetic epistatic analysis in fat body cells. We found that Drosophila fat body clones in which we over-expressed Pcb (the Drosophila gene encoding pyruvate carboxylase) were significantly smaller than controls and were equivalent in size to MPC+ clones (Figure 4e, f; Figure 4—figure supplement 2a–c). Clones expressing both the MPC and Pcb were even smaller (Figure 4e, f; Figure 4—figure supplement 2a–c). Conversely, knockdown of Pcb (Pcb-KD) in MPC-expressing fat body clones completely rescued the cell size phenotype (Figure 4e, f; Figure 4—figure supplement 2d). Knockdown of Pcb in MPC-expressing HepG2 cells also eliminated the small cell size phenotype (Figure 4—figure supplement 2e). These data suggested that the small size of cells expressing the MPC is likely due to increased flux through the PC reaction. Consistent with this, knockdown of the PDH-E1 (Drosophila gene Pdha) or PDH-E2 (Drosophila gene Dlat) subunits of PDH, which should divert mitochondrial pyruvate, so it is preferentially used by PC, also resulted in smaller fat body cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 2f–k). In contrast, activating PDH by knocking down the inhibitory PDH kinases (mammalian PDKs, Drosophila gene Pdk) (Stacpoole, 2017; Wang et al., 2021), which should promote the flux of pyruvate through PDH and away from PC, rescued cell size in MPC-expressing fat body clones (Figure 4—figure supplement 2j, k). Similarly, in MPC-expressing HepG2 cells, activation of PDH via treatment with the PDK inhibitors DCA and AZD7545 was sufficient to restore cell size (Figure 4—figure supplement 2l), (Stacpoole, 2017; Wang et al., 2021). These analyses suggest that the reduction in cell size observed with MPC expression is due to PC-mediated metabolism of pyruvate.

The product of PC, oxaloacetate, has three major metabolic fates: (1) feeding the TCA cycle via citrate synthase as discussed above, (2) conversion to aspartate by glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2 (GOT2), and (3) conversion to phosphoenolpyruvate by PEPCK2, leading to gluconeogenesis, synthesis of glucose (Jitrapakdee et al., 2008; Kiesel et al., 2021). Sustained expression of the MPC in fat bodies increased the concentration of glucose in this tissue (Figure 4g) as well as glucose and trehalose in larval circulation (known as hemolymph) (Figure 4h), suggesting that MPC expression increases glucose production in fat body cells. Next, we tested whether PEPCK2-mediated gluconeogenesis was elevated in these cells compared with controls. We used 13C-lactate to trace the 13C-labeling of phosphoenolpyruvate and resultant glucose synthesis via gluconeogenesis (Figure 4i). We found that the relative abundance of M+3 phosphoenolpyruvate was higher in MPC-expressing cells compared with controls (Figure 4j), suggesting increased activity of PEPCK2. The gluconeogenic pathway employs a series of biochemical reactions to convert phosphoenolpyruvate into glucose, which is then excreted from the cell. This production of M+6 glucose from lactate was also higher in MPC-expressing HepG2 cells (Figure 4k). To test whether gluconeogenesis contributes to the small size phenotype of MPC-expressing cells, we knocked down enzymes in the pathway (Drosophila phosphoenol carboxykinase, Pepck2, and fructose bisphosphatase, Fbp) and assessed cell size in Drosophila and HepG2 models. Knockout of PEPCK2 rescued the size of MPC-expressing HepG2 cells grown in spheroids (Figure 4l) and cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 2m). Knockdown of either Pepck2 or Fbp partially rescued the size defect in MPC-expressing Drosophila fat body clones (Figure 4n, o; Figure 4—figure supplement 2n–r), and Pepck2 knockdown also increased protein synthesis in these clones (Figure 4p, q). Collectively, these data suggest that the cell size and protein synthesis phenotypes observed in MPC-expressing cells require PC-mediated gluconeogenesis, and this relationship is found in both the Drosophila fat body and in HepG2 cells.

A redox imbalance impairs protein synthesis and cell growth in MPC-expressing cells

We were intrigued by the observation that MPC expression exerted its impact on cell size through PC, rather than via increased flux through PDH. We did not observe any differences in the abundances of PDH1a, phosphorylated (Ser-293, inactive) PDH1a, PC, PEPCK2, or G6PC proteins in MPC-expressing HepG2 cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1a, b). We therefore hypothesized that the shift in pyruvate metabolism in response to MPC expression might be driven by changes in the abundances of enzyme cofactors, metabolite regulators, or cellular redox balance. PC and PDH show reciprocal regulation by such factors: PC utilizes ATP as a substrate and is allosterically activated by acetyl-CoA, whereas PDH is inhibited by ATP, acetyl CoA, and NADH (Chai et al., 2022; Sugden and Holness, 2011; Figure 5—figure supplement 1c). In addition, several reactions in gluconeogenesis require ATP or NADH (Hausler et al., 2006; Siess et al., 1977; Figure 5—figure supplement 1c). Upon induction of MPC expression in HepG2 cells, we observed increased abundance of acetyl-CoA (Figure 5—figure supplement 1d), a higher ATP to ADP ratio (Figure 5—figure supplement 1e), a greater abundance of NADH without an increase in NAD+, and thus an increase in the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio (Figure 5—figure supplement 1f–h). To determine how MPC expression impacts the subcellular distribution of redox factors, we separated cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions from control or MPC-expressing Drosophila fat bodies and measured the NADH/NAD+ ratio. We found that MPC expression increased the NADH/NAD+ ratio in both the cytoplasm and mitochondria (Figure 5a). We observed a similar increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio in both fractions in MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids (Figure 5b). It is important to note that these measurements can be confounded by the very rapid redox reactions that can happen post-harvest. Nonetheless, these combined results suggest that the increased abundances of acetyl-CoA, ATP, and NADH in MPC-expressing cells could promote the rewiring of mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism through PC and support gluconeogenesis.

To test the hypothesis that ATP or NADH concentrations might affect cell size in MPC-expressing Drosophila fat body clones or HepG2 cells, we utilized pharmacological or genetic modulation of these molecules. Treatment with gramicidin, which decreases the ATP to ADP ratio (Xue et al., 2022), did not alter the size of MPC-expressing HepG2 cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1i). We used several orthogonal approaches to reduce the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio in the MPC-expressing systems and measured their effect on cell size. Co-expression of the Drosophila nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase (Nmnat), which increases NAD+ biosynthesis, almost normalized the small size phenotype of MPC-expressing clones in the Drosophila fat body (Figure 5c, d). We observed a similar rescue of cell size following expression of the Ciona intestinalis alternate Complex I enzyme NADH dehydrogenase (NDX) (Gospodaryov et al., 2020) or the yeast NADH dehydrogenase (NDI) (Sanz et al., 2010), both of which oxidize NADH to NAD+ without concomitant proton translocation and energy capture (Figure 5e, f). Expression of NDI in HepG2 cells also mitigated the effect of MPC expression on spheroid size (Figure 5—figure supplement 1j, k), as did treatment with duroquinone (Merker et al., 2006; Figure 5—figure supplement 1l), which oxidizes NADH to NAD+. To extend these investigations to three-dimensional culture, we supplemented the growth medium of MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids with the NAD+ precursors nicotinamide riboside (NR) or nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), both of which recovered spheroid size (Figure 5g, h).

Since MPC expression reduced protein synthesis in both Drosophila fat bodies and HepG2 cells, we tested how cellular redox status might contribute to this phenotype in both systems. Expression of NDX, which lowers the NADH/NAD+ ratio, increased translation in MPC-expressing Drosophila fat body clones (Figure 5i, j). In HepG2 spheroids, boosting NAD+ biosynthesis by supplementing growth media with NR or NMN partially rescued the abundance of destabilized GFP (Figure 5k). These results suggest that the elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio in MPC-expressing cells limits protein synthesis and that normalizing that ratio increases protein synthesis and cell size.

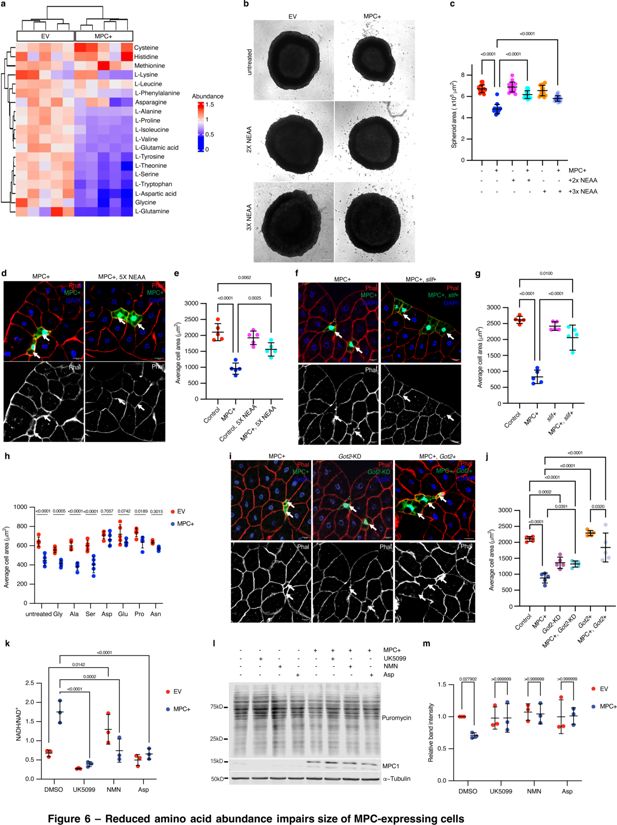

Reduced amino acid abundance impairs the size of MPC-expressing cells

Given the reduced protein synthesis observed upon MPC expression, we assessed amino acid concentrations in HepG2 using steady-state metabolomics. We found that MPC expression reduced the abundance of most amino acids (Figure 6a). To test whether the low abundances of amino acids contribute to the smaller size of MPC-expressing cells, we supplemented the growth media of HepG2 spheroids with excess non-essential amino acids (NEAAs)—either two or three times the recommended dilution of a commercially available amino acid cocktail that includes glycine, L-alanine, L-asparagine, L-aspartate, L-glutamate, L-proline, and L-serine. MPC-expressing spheroids grown with excess NEAAs were comparable in size to controls (Figure 6b, c). In parallel, we provided Drosophila larvae with food containing excess (5x) amino acids from 72 to 120 hr AEL, which partially rescued cell size in MPC-expressing fat body clones (Figure 6d, e). To genetically augment intracellular amino acids, we expressed the amino acid importer slimfast (Colombani et al., 2003) in control or MPC-expressing fat body clones and found that it prevented the decrease in cell size (Figure 6f, g).

Reduced amino acid abundance impairs size of MPC-expressing cells.

(a) A heatmap of the abundances of amino acids in empty vector (EV) and MPC expressing (MPC+) HepG2 cells cultured under standard conditions. Color codes indicate relative abundances for each amino acid: blue (low), green (similar), and yellow (high). (b) Representative bright field images of EV or MPC+ HepG2 spheroids cultured with 2x or 3x the recommended concentration of non-essential amino acids cocktail (NEAA). The scale bar represents 200 µm. (c) Quantification of spheroid areas from EV and MPC+ HepG2 spheroids cultured with 2x or 3x NEAA. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of 30 technical replicates. (d) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat body cells from animals fed a standard diet or a diet supplemented with 5x NEAA. Arrows indicate GFP-positive clones with MPC expression (MPC+). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (e) Quantification of the area of MPC+ fat body clonal cells. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with each data point representing the average size of 20 clones collected from five male larvae. (f) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat body cells. Arrows indicate GFP-positive MPC+ clones and MPC+ and slimfast over-expression (MPC+, Slif+). The scale bar represents 20 µm. (g) Quantification of the area of GFP-positive clones with control, MPC expression, Slimfast overexpression (Slif+) and MPC+ clones with Slimfast overexpression (MPC+, Slif+). Data presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with each 20 clonal cells analyzed for each of the indicated genetic manipulations. (h) Quantification of the cell areas of EV or MPC+ HepG2 cells cultured under standard conditions or with excess of the indicated amino acid—10 mM glycine, 5 mM alanine, 5 mM serine, 5 mM asparagine, 5 mM aspartic acid, 5 mM glutamic acid, or 5 mM proline. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates. (i) Representative images of phalloidin- and DAPI-stained fat body cells. Arrows indicated GFP-positive cells with MPC expression (MPC+), Got2 knockdown (Got2 KD), and Got2 overexpression with MPC expression (MPC+, Got2+). (j) Quantification of the area of GFP-positive clones with control, MPC expression (MPC+), Got2 knockdown (Got2-KD), Got2 knockdown with MPC expression (MPC+, Got2-KD), Got2 overexpression (Got2+), and Got2 overexpression with MPC expression (MPC+, Got2+). Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of five biological replicates, with each 20 clonal cells analyzed for each of the specified genetic manipulations. (k) NADH/NAD+ ratio in cells treated with 10 µM UK5099, 1 µM NMN, or 5 mM aspartate. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates. (l) Western blot analysis of puromycin-labeled (20 µg/ml puromycin for 30 min) nascent protein in EV or MPC+ HepG2 cells cultured with 10 µM UK5099, 1 µM NMN, or 5 mM aspartate. (m) Quantification of intensities of puromycin labeling in EV and MPC+ cell lysates. Unpaired t-tests and one-way ANOVA tests were performed to evaluate the statistical significance of the data, and p-values are noted in the graph if significance is observed.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig6-data1-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 6—source data 2

PDF files containing original western blots for Figure 6i, indicating the relevant bands and treatments.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig6-data2-v1.zip

-

Figure 6—source data 3

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 6i.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig6-data3-v1.zip

To determine which amino acid(s) contribute to the cell size effects of MPC expression, we cultured control and MPC-expressing HepG2 cells in media supplemented with an excess of each amino acid from the NEAA cocktail. Treatment with excess glycine, l-alanine, or L-serine had no effect on cell size (Figure 6h). However, the size of MPC-expressing cells was normalized by supplementation with L-aspartate, L-glutamate, or L-proline (Figure 6h), all of which are derived from TCA cycle intermediates. Supplementation with either L-aspartate or L-glutamate also rescued the small size phenotype of MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids (Figure 6—figure supplement 1a, b). Increasing L-aspartate uptake by over-expressing the aspartate transporter SLC1A3 also recovered size of HepG2 spheroids (Figure 6—figure supplement 1c, d). In addition, treatment with excess (3x) NEAA partially restored the abundance of d2GFP in MPC-expressing HepG2 spheroids (Figure 6—figure supplement 1e), suggesting rescued protein synthesis.

Like glutamate and proline, aspartate is derived from a TCA cycle intermediate, specifically via transamination of oxaloacetate by glutamic-oxaloacetate transaminase 2 (GOT2). Since GOT2 and PEPCK2 both utilize oxaloacetate as a substrate, we hypothesized that knocking down GOT2 might phenocopy MPC expression by driving PEPCK2-mediated conversion of oxaloacetate into phosphoenolpyruvate and thereby suppressing aspartate biosynthesis. Knockdown of Got2 (the Drosophila gene encoding GOT2) reduced cell size in Drosophila fat body clones and phenocopied MPC-expressing cells (Figure 6i, j; Figure 6—figure supplement 1f–h). Similarly, both GOT2 knock-out and MPC-expressing HepG2 cells were smaller than EV (Figure 6—figure supplement 1i). Expression of the MPC in these GOT2 knockdown systems had no significant impact on cell size (Figure 6i, j; Figure 6—figure supplement 1i), suggesting that the effects of MPC expression and GOT2 knockdown act similarly to limit amino acid synthesis and cell size. We next performed the reciprocal experiment by over-expressing Got2 to favor the production of aspartate from oxaloacetate. Got2 expression normalized cell size in both MPC-expressing fat body clones and in HepG2 spheroids (Figure 6i, j; Figure 6—figure supplement 1j, k). The efflux of aspartate from mitochondria into the cytoplasm is a critical component of the malate-aspartate shuttle, which is a major redox shuttle in human cells. To test whether increasing the abundance of aspartate would ameliorate the high NADH/NAD+ ratio observed in MPC-expressing cells, we supplemented growth media with exogenous aspartate and assessed cellular redox status. We found that excess aspartate reduced the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio in these cells such that it was comparable with control cells (Figure 6k). We observed similar results when we treated these cells with NMN or UK5099 (Figure 6k). Moreover, all these treatments increased protein synthesis in MPC-expressing cells (Figure 6l, m).

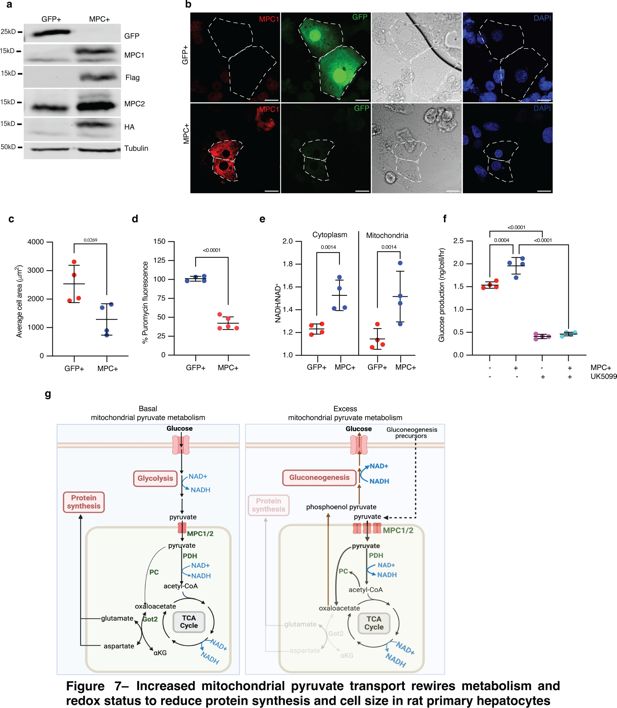

Mitochondrial pyruvate import reduces the size of rat primary hepatocytes

Although HepG2 cells exhibit some features of hepatocytes, they are a transformed, immortalized, and proliferative hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. We wanted to test whether the MPC expression phenotypes that we observed in Drosophila fat bodies and HepG2 cells could be recapitulated in a more physiologically relevant mammalian model. We chose primary rat hepatocytes, which have been used extensively to interrogate hepatocyte cell metabolism and signaling and also have the advantage of being genetically tractable. We expressed MPC1 and MPC2 in cultured primary rat hepatocytes (Figure 7a), and, consistent with our results in other systems, we found that expression of MPC reduced cell size (Figure 7b, c) and decreased protein synthesis (Figure 7d). MPC-expressing primary hepatocytes also had a higher NADH to NAD+ ratio in both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions (Figure 7e). We assessed gluconeogenesis in primary hepatocytes by quantifying glucose in the culture media following incubation with the gluconeogenic precursors, pyruvate, and lactate. Glucose production was higher in MPC-expressing hepatocytes compared with controls (Figure 7f). Treatment with UK5099 eliminated this effect and reduced glucose production to a similar rate in both cells (Figure 7f). These results demonstrate that augmented mitochondrial pyruvate in hepatocytes and related cells in Drosophila drives a metabolic program that results in an increased NADH/NAD+ ratio. This scenario results in accelerated gluconeogenesis, decreased protein synthesis, and reduced cell size.

Increased mitochondrial pyruvate transport rewires metabolism and redox status to reduce protein synthesis and cell size in rat primary hepatocytes.

(a) Western blot analysis of MPC expression in cultured rat primary hepatocytes. (b) Representative confocal images of rat primary hepatocytes expressing exogenous GFP or MPC. DIC images and DAPI staining of nuclei are also shown. Cell boundaries are marked with dotted lines. The scale bar represents 20 µm. (c) Quantification of the areas of GFP and MPC expressing primary hepatocytes. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of six biological replicates, with 20 hepatocytes analyzed for GFP and MPC+. (d) Fluorescence intensity of puromycin-labeled nascent proteins in GFP and MPC+ primary hepatocytes. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of six biological replicates, with 20 hepatocytes analyzed for each condition. (e) Quantification of glucose in the culture media of primary hepatocytes transfected with GFP or MPC constructs, conditioned with 20 mM lactate and 2 mM pyruvate for 4 hr. 10 µM UK5099 was used to inhibit MPC’s downstream impact on gluconeogenesis. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates. (f) NADH/NAD+ ratios in the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions of GFP or MPC+ primary hepatocytes. Data is presented as mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates. (g) Schematics illustrating the metabolic consequences of excess mitochondrial pyruvate in hepatocytes. Under normal conditions, mitochondrial pyruvate fuels the TCA cycle, maintaining redox balance and generating sufficient amino acids for cellular homeostasis. However, when mitochondrial pyruvate transport is increased and excess pyruvate is metabolized, both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic redox states are altered. This excess pyruvate enhances the activities of pyruvate carboxylase (PC), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and the TCA cycle, leading to an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio. The oxaloacetate produced by PC is converted into phosphoenolpyruvate via PEPCK2, promoting gluconeogenesis. This shift reduces the availability of aspartate and related amino acids necessary for protein synthesis, ultimately resulting in a reduction in cell size without impacting the canonical cell growth signaling pathways. Panel g was created with BioRender.com.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Source data related to Figure 7.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig7-data1-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 7—source data 2

PDF files containing original western blots for Figure 7a, indicating the relevant bands and treatments.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig7-data2-v1.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 3

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 7a.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig7-data3-v1.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 4

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 7a.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig7-data4-v1.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 5

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 7a.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/103705/elife-103705-fig7-data5-v1.zip

Discussion

We investigated whether pyruvate metabolism influences biosynthetic capacity and cell size in the Drosophila fat body and in HepG2 spheroids. During the third instar phase of Drosophila larval growth, when cells are rapidly expanding in size, we observed a profoundly decreased expression of the MPC in liver-like fat body cells. We found that this rewiring of pyruvate metabolism is essential for cell growth, as forced maintenance of MPC expression resulted in dramatically smaller cells. By combining Drosophila genetic analyses and metabolomics studies in HepG2 cells and spheroids, we demonstrated that excess mitochondrial pyruvate elevates the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio and redirects carbohydrate metabolism to favor gluconeogenesis over glycolysis (Figure 7g). This shift reduces the availability of oxaloacetate for aspartate and glutamate biosynthesis, triggering a broader imbalance in amino acid abundances within the cell. We conclude that altering the fate of pyruvate to support biomass accumulation is required for the cell size expansion that occurs during fat body development. We speculate that this phenomenon also applies to the mammalian liver, which is the closest analog of the Drosophila fat body, as both HepG2 cells and primary rat hepatocytes show similar effects following ectopic MPC expression.

Why does simply reorienting the metabolism of pyruvate have this profound effect on cell growth? Our data suggest that a central mediator of the phenotype is an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio, which likely results from MPC expression driving an acceleration of the TCA cycle, as evidenced by an increase in the abundances of M+2 isotopomers of TCA cycle intermediates. Although the increase in labeled succinate, fumarate, and malate is modest, it occurs despite a reduction in glycolytic labeling. This suggests that less labeled pyruvate feeds the TCA in MPC-expressing cells compared with controls and that we are likely underestimating the actual increase in flux. The TCA cycle generates NADH and appears to do so more actively in cells with ectopically expressed MPC. However, our oxygen consumption data suggest that the oxidative phosphorylation system in these cells does not have the capacity to increase its activity in response to the enhanced availability of mitochondrial pyruvate and an increased NADH/NAD+ ratio. As a result, the increased TCA cycle flux and limited ETC activity together elevate the NADH/NAD+ ratio in both the mitochondria and cytoplasm, disrupting cellular redox balance leading to a rewiring of cellular metabolism.

This redox situation causes two distinct but related perturbations that appear to both contribute to decreased cell growth. First, we observed a clear depletion of amino acids and evidence of decreased synthesis of amino acids that are primarily derived from TCA cycle intermediates (aspartate, glutamate, and proline). A reduced NAD+ pool impairs the capacity of cells to synthesize aspartate (Birsoy et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2018), which is used to synthesize glutamate and proline and which plays a crucial role in maintaining redox balance in both the mitochondria and cytoplasm (Alkan et al., 2018; Holeček, 2023a; Lieu et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2020). Replenishing any of these TCA cycle-derived amino acids via genetic or nutritional increases in their availability was sufficient to reverse the effect of ectopic MPC expression on cell size. Thus, amino acid depletion is a key driver of the small size phenotype. Second, the increased NADH/NAD+ ratio also drives a particular metabolic program that favors the conversion of mitochondrial pyruvate to oxaloacetate and a subsequent increase in gluconeogenesis. This program is enforced by allosteric regulation via NADH, acetyl-CoA, and ATP, which act on PC and several enzymes of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. It also appears to be important for the small size of MPC-expressing cells since loss of any of several steps along the gluconeogenic pathway, particularly PC and PEPCK2, mitigates or eliminates the cell size phenotype observed with ectopic MPC expression in fat body cells and HepG2 spheroids. It is important to note that gluconeogenesis is a critical function of these cells, and its rate is carefully controlled in response to varying physiological stimuli. Surprisingly, constitutive MPC expression is sufficient to supersede the control enacted by physiological and hormonal signals and enact the loss of biomass and impaired cell size.

We have previously shown that loss of the MPC enhanced the stem cell identity and proliferation of intestinal stem cells, whereas ectopic MPC expression had the opposite effect (Bensard et al., 2020; Schell et al., 2017). Such observations are consistent with our findings that MPC expression inversely correlates with biomass accumulation. More recent data demonstrated that enhanced MPC activity prevented the increase in cell size that occurs in cardiomyocytes in response to hypertrophic signaling (Cluntun et al., 2021; Fernandez-Caggiano et al., 2020). In these cases, the fate of mitochondrial pyruvate that determines cell growth is its oxidation in the TCA cycle. In contrast, our studies of hepatocytes and related cells described herein demonstrate that the fate of pyruvate that suppresses growth in cell size is not oxidation by the TCA cycle, but rather the production of glucose, which starts with its conversion to oxaloacetate by PC in the mitochondria. Cardiomyocytes have low expression of PC compared with liver, where this enzyme (as well as others including PEPCK2) serves a vital role during fasting by producing glucose, which fuels the brain and other organs that require glucose for their survival and function (Hatting et al., 2018; Petersen et al., 2017; Rui, 2014). This is an example of how the unique metabolic physiology of specialized cells plays a critical role in maintaining organismal homeostasis.

One conclusion from the data presented herein is that a cell’s metabolic program plays a decisive role in determining the growth of that cell. It was striking how rapidly expression of the MPC impacted cell size in the HepG2 model. Essentially, as soon as MPC overexpressionbecame detectable, the population of cells started to show a decrease in size. Notably, the decrease in cell size following ectopic MPC expression occurred despite the upregulation of multiple pro-growth signaling networks. It is unclear why these networks are hyperactivated in this context as there is no evidence from our data indicating any nutrients are in excess abundance. We hypothesize that there may be regulators of cell size that recognize when cells are inappropriately small and engage these pathways to increase cell size. mTORC1, PI3K, and Myc pathways typically promote biomass accumulation and increased cell size but fail to do so when mitochondrial pyruvate is elevated. MPC expression reduced the abundance of amino acids, and this appears to play a dominant role in impairing protein synthesis and preventing the cell growth effects expected following hyperactivation of the mTORC1 and Myc pathways. Thus, our data suggest that the metabolic fate of pyruvate can override canonical pathways that mediate cell size—such as mTORC1 signaling.

We demonstrate that the appropriate partitioning of pyruvate metabolism maintains the redox state of a cell to support the accumulation of biomass that is necessary for its specialized function. Increased mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism in cells from the fly ‘liver-like’ fat body disrupts these processes, causes cells to perform excess gluconeogenesis, and prevents cell growth. As a result, the Drosophila larvae became hyperglycemic and experienced developmental delay. The abundances of MPC1 and MPC2 are upregulated in mouse livers during starvation and in high-fat diet conditions, which correlates with increased rates of gluconeogenesis in both circumstances. Conversely, loss of the MPC in the liver impairs gluconeogenesis (Gray et al., 2015; McCommis et al., 2015; Yiew and Finck, 2022). Moreover, liver dysfunction in diabetes and hepatic steatosis is driven by reductive stress and an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio (Goodman et al., 2020; Jokinen and Luukkonen, 2024). We are intrigued by the possibility that the fate of pyruvate might have profound consequences on the redox state and gluconeogenic capacity of the mammalian liver, including by functioning as part of the metabolic milieu that drives unrestrained gluconeogenesis in diabetes. Our discovery that mitochondrial pyruvate regulates the cellular redox state, thereby controlling biosynthesis, offers insights for developing therapeutic strategies for these and other diseases.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains and handling

Request a detailed protocolDrosophila melanogaster stocks were maintained at 25°C on semi-defined fly food composed of 20 g agar, 80 g baker’s yeast, 30 g sucrose, 60 g glucose, 0.5 g MgSO4, 0.5 g CaCl2, 11 ml tegosept, and 6 ml propionic acid. This was the base medium for all Drosophila experiments, but specific fly food modifications are mentioned in text and figure legends. To induce clones in fat bodies, synchronized eggs were transferred to 29°C for 4 days until dissection. For experiments involving genetic manipulation of all fat body cells, tubGal80ts20 was used to restrict activity of CG-Gal4 at 18°C for 120 hr (57 hr equivalent time at 25°C) and larvae were shifted to 29°C till dissection at specified time points.

Following fly stocks were procured from Bloomington stock center UAS-MPC1-P2A-MPC2 (28812582), CG-Gal4; tubGal80ts20, hs-Flp1.22 (BDSC, #77928), Act >CD2>Gal4, UAS-GFP (BDSC, #4413), Act >CD2>Gal4, UAS-RFP (BDSC, #30558), UAS-S6KSTDETE (BDSC, #6914), UAS-RhebPA (BDSC, #9689), UAS-MycOE (BDSC, #9675), UAS-MycRNAi (BDSC, #25783), UAS-PI3K93E.Excel (BDSC, #8287), UAS-PI3K93EA2860C (BDSC, #8288), UAS-TSC1RNAi (BDSC, #31314), UAS-hPC (BDSC, #77928), UAS-PCRNAi (BDSC, #56883), UAS-PEPCK2RNAi (BDSC, #36915), UAS-FBPaseRNAi (BDSC, #51871), UAS-PdkRNAi (BDSC, #35142), UAS-NMNAT (BDSC, #37002), UAS-CintNDX (BDSC, #93883), UAS-ScerNDI1 (BDSC, #93878), UAS-Slif (BDSC, #52661), UAS-GOT2RNAi (BDSC, #78778). From VDRC UAS-MPC1RNAi(KK) and from NIG UAS-PdhaRNAi, UAS-DlatRNAi (PDH E2) were purchased.

Generation of overexpression and CRISPR mutant fly stock