Plasmodium P36 determines host cell receptor usage during sporozoite invasion

Abstract

Plasmodium sporozoites, the mosquito-transmitted forms of the malaria parasite, first infect the liver for an initial round of replication before the emergence of pathogenic blood stages. Sporozoites represent attractive targets for antimalarial preventive strategies, yet the mechanisms of parasite entry into hepatocytes remain poorly understood. Here we show that the two main species causing malaria in humans, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, rely on two distinct host cell surface proteins, CD81 and the Scavenger Receptor BI (SR-BI), respectively, to infect hepatocytes. By contrast, CD81 and SR-BI fulfil redundant functions during infection by the rodent parasite P. berghei. Genetic analysis of sporozoite factors reveals the 6-cysteine domain protein P36 as a major parasite determinant of host cell receptor usage. Our data provide molecular insights into the invasion pathways used by different malaria parasites to infect hepatocytes, and establish a functional link between a sporozoite putative ligand and host cell receptors.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25903.001eLife digest

Malaria is an infectious disease that affects millions of people around the world and remains a major cause of death, especially in Africa. It is caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are transmitted by mosquitoes to mammals. Once in the mammal, the parasites infect liver cells, where they multiply. Previous studies have suggested that proteins on the surface of the liver cells and on the parasite affect how Plasmodium infects liver cells. Understanding how these proteins enable the parasites to enter the cells may help researchers to develop treatments that interrupt the parasite life cycle and prevent infection.

Manzoni et al. have now investigated how different malaria parasite species interact with liver cells. The main parasite species that infect humans are Plasmodium falciparum in Africa and Plasmodium vivax outside Africa. Manzoni et al. found that P. falciparum and P. vivax infect human liver cells by two different routes: P. falciparum interacts with a liver cell protein called CD81, and P. vivax interacts with a liver cell protein called SR-BI. Further experiments that used mutant forms of malaria parasites that infect mice showed that a parasite protein called P36 determines which liver cell protein the parasite will interact with.

The next step is to understand how P36 interacts with the liver cell proteins and to identify other parasite proteins that help Plasmodium to invade cells. In the future, such knowledge may help to develop a highly effective malaria vaccine.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25903.002Introduction

Hepatocytes are the main cellular component of the liver and the first replication niche for the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium. Malaria begins with the inoculation of sporozoites into the host skin by infected Anopheles mosquitoes. Sporozoites rapidly migrate to the liver and actively invade hepatocytes by forming a specialized compartment, the parasitophorous vacuole (PV), where they differentiate into thousands of merozoites (Ménard et al., 2013). Once released in the blood, merozoites invade and multiply inside erythrocytes, causing the malaria disease.

Under natural transmission conditions, infection of the liver is an essential, initial and clinically silent phase of malaria, and therefore constitutes an ideal target for prophylactic intervention strategies. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying Plasmodium sporozoite entry into hepatocytes remain poorly understood. Highly sulphated proteoglycans in the liver sinusoids are known to bind the circumsporozoite protein, which covers the parasite surface, and contribute to the homing and activation of sporozoites (Frevert et al., 1993; Coppi et al., 2007). Subsequent molecular interactions leading to sporozoite entry into hepatocytes have not been identified yet. Several parasite proteins have been implicated, such as the thrombospondin related anonymous protein (TRAP) (Matuschewski et al., 2002), the apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1) (Silvie et al., 2004), or the 6-cysteine domain proteins P52 and P36 (van Dijk et al., 2005; Ishino et al., 2005; van Schaijk et al., 2008; Kaushansky et al., 2015; Labaied et al., 2007), however their role during sporozoite invasion remains unclear (Bargieri et al., 2014).

Our previous work highlighted the central role of the host tetraspanin CD81, one of the receptors for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Pileri et al., 1998), during Plasmodium liver infection (Silvie et al., 2003). CD81 is an essential host entry factor for human-infecting P. falciparum and rodent-infecting P. yoelii sporozoites (Silvie et al., 2003, 2006a). CD81 acts at an early step of invasion, possibly by providing signals that trigger the secretion of rhoptries, a set of apical organelles involved in PV formation (Risco-Castillo et al., 2014). Whereas CD81 binds the HCV E2 envelope protein (Pileri et al., 1998), there is no evidence for such a direct interaction between CD81 and Plasmodium sporozoites (Silvie et al., 2003). Rather, we proposed that CD81 acts indirectly, possibly by regulating an as yet unidentified receptor for sporozoites within cholesterol-dependent tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (Silvie et al., 2006b; Charrin et al., 2009a). Intriguingly, the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei can infect cells lacking CD81 (Silvie et al., 2003, 2007), however the molecular basis of this alternative entry pathway was until now totally unknown.

Another hepatocyte surface protein, the scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI), was shown to play a dual role during malaria liver infection, first in promoting parasite entry and subsequently its development inside hepatocytes (Yalaoui et al., 2008a; Rodrigues et al., 2008). However, the contribution of SR-BI during parasite entry is still unclear. SR-BI, which is also a HCV entry factor (Scarselli et al., 2002; Bartosch et al., 2003), binds high-density lipoproteins with high affinity and mediates selective cellular uptake of cholesteryl esters (Acton et al., 1996). Yalaoui et al. reported that SR-BI is involved indirectly during P. yoelii sporozoite invasion, by regulating the levels of membrane cholesterol and the expression of CD81 and its localization in tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (Yalaoui et al., 2008a). In another study, Rodrigues et al. observed a reduction of P. berghei invasion of Huh-7 cells upon SR-BI inhibition (Rodrigues et al., 2008). Since CD81 is not required for P. berghei sporozoite entry into Huh-7 cells (Silvie et al., 2007), these results suggested a CD81-independent role for SR-BI. More recently, Foquet et al. showed that anti-CD81 but not anti-SR-BI antibodies inhibit P. falciparum sporozoite infection in humanized mice engrafted with human hepatocytes (Foquet et al., 2015), questioning the role of SR-BI during P. falciparum infection.

These conflicting results prompted us to revisit the contribution of SR-BI during P. falciparum, P. yoelii and P. berghei sporozoite infections. For the first time, we also explored the role of CD81 and SR-BI during hepatocyte infection by P. vivax, a widely distributed yet highly neglected cause of malaria in humans, for which the contribution of hepatocyte surface receptors has not been investigated to date.

Here, we show that SR-BI is an important entry factor for P. vivax but not for P. falciparum or P. yoelii sporozoites. Remarkably, SR-BI and CD81 fulfil redundant functions during host cell invasion by P. berghei sporozoites, which can use one or the other molecule. We further investigated parasite determinants associated with host cell receptor usage. We show that genetic depletion of P52 and P36, two members of the Plasmodium 6-cysteine domain protein family, abrogates sporozoite productive invasion and mimics the inhibition of CD81 and/or SR-BI entry pathways, in both P. berghei and P. yoelii. Finally, we identify P36 as the molecular driver of P. berghei sporozoite entry via SR-BI. Our data, by revealing a functional link between parasite and host cell entry factors, pave the way towards the identification of ligand-receptor interactions mediating Plasmodium infection of hepatocytes, and open novel perspectives for preventive and therapeutic approaches.

Results

Antibodies against SR-BI inhibit P. vivax but not P. falciparum or P. yoelii sporozoite infection

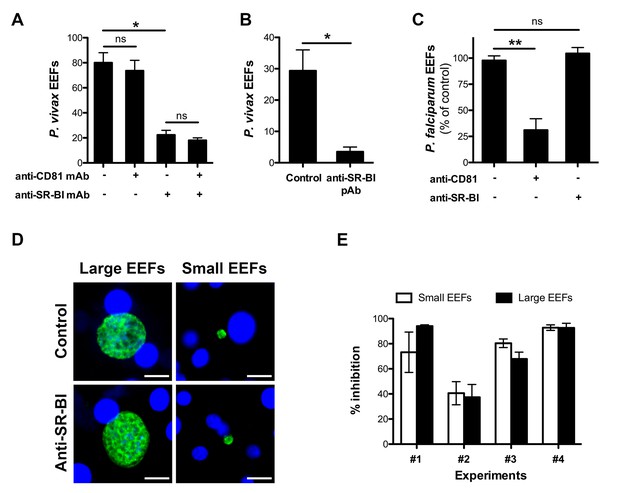

To evaluate the contribution of CD81 and SR-BI during P. vivax infection, we tested the effects of neutralizing CD81- and/or SR-BI- specific antibodies on P. vivax sporozoite infection in primary human hepatocyte cultures (Mazier et al., 1984). A monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the main extracellular domain of CD81, previously shown to inhibit P. falciparum sporozoite infection (Silvie et al., 2003), had no effect on the number of P. vivax-infected cells in vitro (Figure 1A). In sharp contrast, a mouse mAb specific for SR-BI (Zahid et al., 2013) greatly reduced infection, with no additive effect of anti-CD81 antibodies (Figure 1A). The same inhibitory effect was observed using polyclonal anti-SR-BI antibodies (Figure 1B). We performed the same experiments with P. falciparum sporozoites and found that anti-CD81 but not anti-SR-BI antibodies inhibit P. falciparum infection in vitro (Figure 1C), in agreement with the in vivo data from Foquet et al (Foquet et al., 2015). These data strongly suggest that P. vivax and P. falciparum sporozoites use distinct entry pathways to infect hepatocytes, reminiscent of the differences between P. berghei and P. yoelii (Silvie et al., 2003).

Anti-SR-BI antibodies inhibit P. vivax but not P. falciparum sporozoite infection.

(A) Primary human hepatocyte cultures were incubated with P. vivax sporozoites in the presence of anti-CD81 and/or anti-SR-BI mAbs at 20 μg/ml, and the number of EEF-infected cells was determined 5 days post-infection after labeling of the parasites with anti-HSP70 antibodies. (B) Primary human hepatocytes were incubated with P. vivax sporozoites in the presence or absence of anti-SR-BI polyclonal rabbit serum (diluted 1/100), and the number of EEFs was determined at day 5 by immunofluorescence. (C) Primary human hepatocyte cultures were incubated with P. falciparum sporozoites in the presence of anti-CD81 mAb (20 μg/ml) and/or anti-SR-BI polyclonal rabbit serum (diluted 1/100), and the number of EEF-infected cells was determined 5 days post-infection after labeling of the parasites with anti-HSP70 antibodies. Results from three independent experiments are shown and expressed as the percentage of control (mean ±SD). (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of P. vivax EEFs at day 5 post-infection of primary human hepatocytes. Parasites were labeled with anti-HSP70 antibodies (green), and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Large EEFs and small EEFs were observed in both control and anti-SR-BI antibody-treated cultures. Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) Inhibitory activity of anti-SR-BI antibodies on small EEFs (white histograms) and large EEFs (black histograms). The results from four independent experiments are shown, and are expressed as the percentage of inhibition observed with anti-SR-BI antibodies as compared to the control.

Two distinct populations of P. vivax exo-erythrocytic forms (EEFs) could be distinguished in the infected cultures, large EEFs representing replicating schizonts, and small EEFs that may correspond to hypnozoites (Dembele et al., 2011) (Figure 1D). Anti-SR-BI antibodies reduced the numbers of large and small EEFs to the same extent (Figure 1E), suggesting an effect on sporozoite invasion rather than on parasite intracellular development.

SR-BI is required for productive invasion of CD81-null cells by P. berghei sporozoites

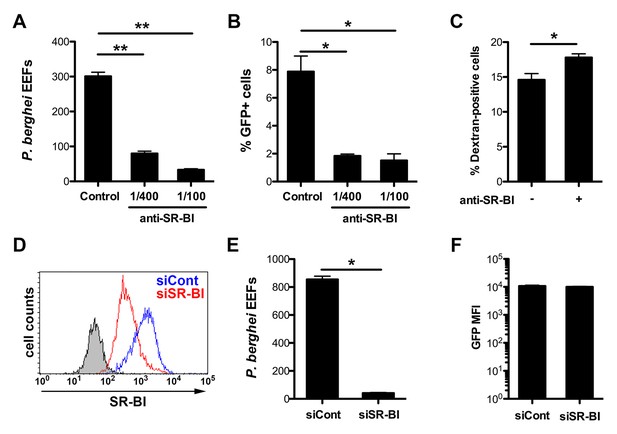

In order to investigate in more details the role of SR-BI during sporozoite entry, we used the more tractable rodent malaria parasite P. berghei. Indeed, P. berghei sporozoites readily infect HepG2 cells, which lack CD81 (Charrin et al., 2001; Berditchevski et al., 1996) but express high levels of SR-BI (Figure 2—figure supplement 1), raising the possibility that this rodent parasite uses a SR-BI route to infect CD81-null cells. To test this hypothesis, P. berghei sporozoites constitutively expressing GFP (PbGFP) (Manzoni et al., 2014) were incubated with HepG2 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of polyclonal anti-SR-BI rabbit antibodies. We observed a dramatic and dose-dependent reduction of the number of EEF-infected cells induced by anti-SR-BI antibodies (Figure 2A). Quantification of host cell invasion by FACS demonstrated that the rabbit anti-SR-BI antibodies block infection at the invasion step (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained with polyclonal rat antibodies and a mouse mAb directed against human SR-BI (Figure 2—figure supplement 2).

Infection of human HepG2 cells by P. berghei sporozoites depends on SR-BI.

(A) HepG2 cells were incubated with P. berghei sporozoites for 3 hr in the absence (Control) or presence of increasing concentrations of rabbit polyclonal SR-BI antisera. Infected cultures were further incubated for 24 hr before quantification of EEFs-infected cells by fluorescence microscopy. (B) HepG2 cell cultures were infected with PbGFP sporozoites as in A, and the number of invaded cells (GFP+) was quantified by FACS 3 hr post-infection. (C) HepG2 cells were incubated for 3 hr with PbGFP sporozoites and rhodamine-labeled dextran, in the presence or absence of anti-SR-BI antibodies. The percentage of traversed (dextran-positive) cells was then determined by FACS. (D) HepG2 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting SR-BI (siSR-BI, red histogram) or with a control siRNA (siCont, blue histogram) were stained with anti-SR-BI antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The negative staining control is in grey. (E) P. berghei EEF number in HepG2 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting SR-BI (siSR-BI) or a control siRNA (siCont). (F) HepG2 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting SR-BI (siSR-BI) or a control siRNA (siCont) were infected with PbGFP sporozoites and incubated for 24 hr, before measurement of the mean fluorescence intensity (GFP MFI) of infected (GFP-positive) cells by FACS.

As a complementary approach, we used small interfering RNA (siRNA) to specifically knockdown SR-BI expression in HepG2 cells (Figure 2D). SR-BI silencing caused a dramatic reduction of the number of EEF-infected cells (Figure 2E), but had no significant effect on the intracellular development of the few invaded parasites (Figure 2F). Plasmodium sporozoites migrate through several cells before invading a final one inside a PV (Mota et al., 2001). Sporozoite cell traversal was increased in SR-BI-depleted HepG2 cells, as compared to the control (Figure 2—figure supplement 3). This is likely due to the robust cell traversal activity of P. berghei sporozoites, which continue to migrate through cells when productive invasion is impaired. Altogether, these data establish that SR-BI is a major entry factor for P. berghei sporozoites in CD81-null HepG2 cells.

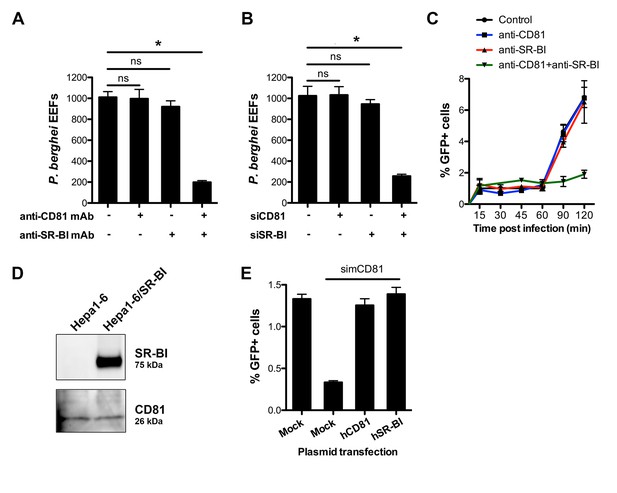

CD81 and SR-BI play redundant roles during P. berghei sporozoite invasion

We next tested whether the presence of CD81 would affect SR-BI function during P. berghei sporozoite infection. We monitored invasion and replication of P. berghei sporozoites in HepG2 cells genetically engineered to express CD81 (HepG2/CD81) (Figure 2—figure supplement 1) (Silvie et al., 2006a), in the presence of anti-SR-BI and/or anti-CD81 antibodies. Strikingly, unlike in CD81-null HepG2 cells, anti-SR-BI antibodies had no inhibitory effect on P. berghei infection in HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 3A). Remarkably, whilst neither anti-SR-BI nor anti-CD81 antibodies alone had any significant impact on invasion (Figure 3A) or parasite intracellular development (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), the combination of CD81 and SR-BI antibodies markedly reduced the number of infected cells (Figure 3A). Similarly, siRNA-mediated silencing of either CD81 or SR-BI alone had no effect on infection, whereas simultaneous silencing of both factors greatly reduced infection (Figure 3B).

CD81 and SR-BI define alternative entry routes for P. berghei sporozoites.

(A) HepG2/CD81 cells were incubated with P. berghei sporozoites in the presence or absence of anti-human CD81 and/or SR-BI mAbs, and the number of EEFs-infected cells was determined by fluorescence microscopy 24 hr post-infection. (B) P. berghei EEF numbers in HepG2/CD81 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting CD81 (siCD81) and/or SR-BI (siSR-BI). (C) HepG2/CD81 cells were incubated with PbGFP sporozoites for 15–120 min, in the presence or absence of anti-CD81 and/or anti-SR-BI antibodies, then trypsinized and directly analyzed by FACS to quantify invaded (GFP-positive) cells. (D) Protein extracts from Hepa1-6 cells and Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with a human SR-BI expression plasmid were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies recognizing mouse and human SR-BI (Abcam) or mouse CD81 (MT81). (E) Hepa1-6 cells were transfected first with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting endogenous mouse CD81 (simCD81), then with plasmids encoding human CD81 (hCD81) or SR-BI (hSR-BI). Cells were then incubated with PbGFP sporozoites, and the number of infected (GFP-positive) cells was determined 24 hr post-infection by FACS.

Blocking both CD81 and SR-BI was associated with an increase in cell traversal activity (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), suggesting that the concomitant neutralization of the two host factors prevented commitment to productive invasion. To directly test this hypothesis, we analysed the invasion kinetics of PbGFP sporozoites in HepG2/CD81 cells, in the presence of anti-SR-BI and/or anti-CD81 neutralizing antibodies. We have shown that in vitro sporozoite invasion follows a two-step kinetics (Risco-Castillo et al., 2015), with initially low invasion rates at early time points, reflecting cell traversal activity, followed by a second phase of productive invasion associated with PV formation. In HepG2/CD81 cells, the invasion kinetics of P. berghei sporozoites in the presence of anti-SR-BI or anti-CD81 specific antibodies were comparable to those of the control without antibody (Figure 3C). In sharp contrast, blocking both CD81 and SR-BI simultaneously suppressed the second phase of productive invasion (Figure 3C). Based on these results, we conclude that SR-BI and CD81 are involved in the commitment to productive entry.

P. berghei sporozoites infect mouse hepatocytic Hepa1-6 cells via a CD81-dependent pathway, as shown by efficient inhibition of infection by CD81 specific antibodies or siRNA (Silvie et al., 2007). Interestingly, we failed to detect SR-BI in Hepa1-6 cells (Figure 3D), providing a plausible explanation as to why CD81 is required for P. berghei infection in this model. We tested whether ectopic expression of SR-BI would rescue P. berghei infection of Hepa1-6 cells upon silencing of endogenous murine CD81 by siRNA. CD81-silenced Hepa1-6 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding human SR-BI or CD81, before exposure to P. berghei sporozoites. The number of infected cells was greatly reduced in CD81-silenced cells as compared to control non-silenced cells (Figure 3E), in agreement with our previous observations (Silvie et al., 2007). Remarkably, transfection of either human CD81 or human SR-BI was sufficient to rescue infection in CD81-silenced cells (Figure 3E), demonstrating that the two receptors can independently perform the same function to support P. berghei infection. Collectively, our data provide direct evidence that CD81 and SR-BI play redundant roles during productive invasion of hepatocytic cells by P. berghei sporozoites.

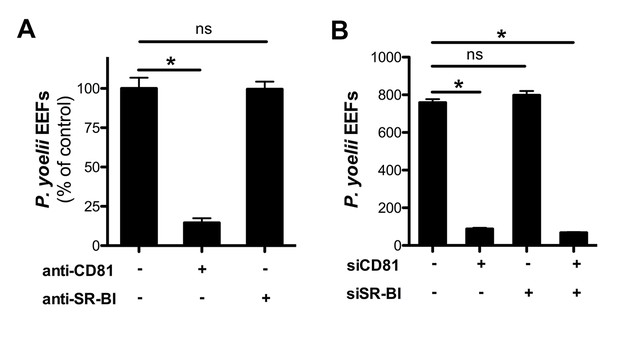

P. yoelii sporozoites require host CD81 but not SR-BI for infection

We next investigated the contribution of SR-BI to P. yoelii sporozoite infection in HepG2/CD81 cells. P. yoelii infection was dramatically reduced by anti-CD81 antibodies, consistent with our previous work (Silvie et al., 2006a), but strikingly was not affected by anti-SR-BI antibodies (Figure 4A). In addition, P. yoelii infection was not affected by siRNA-mediated silencing of SR-BI, but was almost abolished upon knockdown of CD81 (Figure 4B). These results indicate that CD81 but not SR-BI plays a central role during P. yoelii sporozoite invasion in HepG2/CD81 cells, similarly to P. falciparum in human hepatocytes.

Infection of HepG2/CD81 cells by P. yoelii sporozoites depends on CD81 but not SR-BI.

(A) HepG2/CD81 cells were incubated with P. yoelii sporozoites in the presence of anti-CD81 mAb (20 μg/ml) or anti-SR-BI polyclonal rabbit serum (diluted 1/100), and the number of EEF-infected cells was determined 24 hr post-infection by fluorescence microscopy. Results from three independent experiments are shown and expressed as the percentage of control (mean ± SD). (B) P. yoelii EEF numbers in HepG2/CD81 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting CD81 (siCD81) and/or SR-BI (siSR-BI).

The 6-cysteine domain proteins P52 and P36 are required for sporozoite productive invasion irrespective of the host cell entry pathway

The data above show that P. berghei sporozoites can use either CD81 or SR-BI to infect hepatocytic cells, whereas P. yoelii utilizes CD81 but not SR-BI, suggesting that one or several P. berghei factors may be specifically associated with SR-BI usage. Among potential candidate parasite factors involved in sporozoite entry, we focused on the 6-cysteine domain proteins P52 and P36, two micronemal proteins of unknown function previously implicated during liver infection (van Dijk et al., 2005; Ishino et al., 2005; van Schaijk et al., 2008; Kaushansky et al., 2015; Labaied et al., 2007; VanBuskirk et al., 2009; Mikolajczak et al., 2014). To facilitate monitoring of the role of P52 and P36 during host cell invasion, we used a Gene Out Marker Out (GOMO) strategy (Manzoni et al., 2014) to generate highly fluorescent p52/p36-knockout parasite lines in P. berghei (Figure 5—figure supplement 1) and P. yoelii (Figure 5—figure supplement 2). Pure populations of GFP-expressing, drug selectable marker-free PbΔp52/p36 and PyΔp52/p36 blood stage parasites were obtained and transmitted to mosquitoes in order to produce sporozoites.

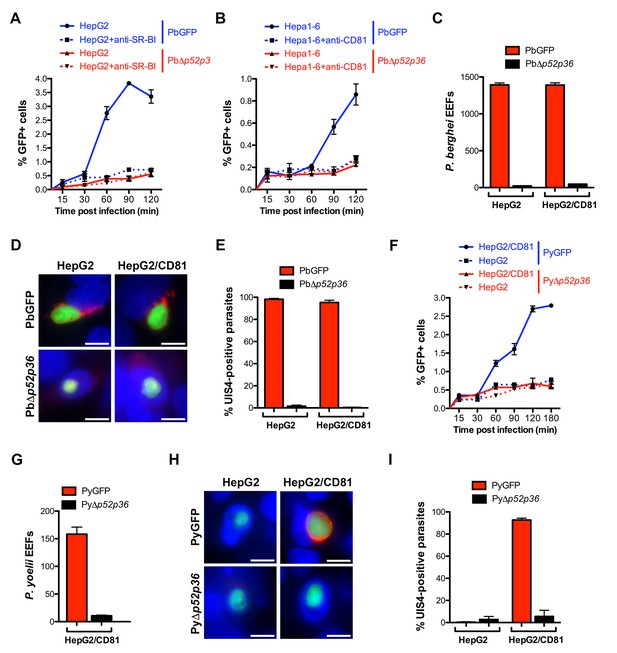

Analysis of the kinetics of PbΔp52/p36 sporozoite invasion by FACS, in comparison to control PbGFP sporozoites, revealed that genetic ablation of p52/p36 abrogates sporozoite productive invasion of HepG2 (SR-BI-dependent entry pathway) and Hepa1-6 cells (CD81-dependent entry pathway) (Figure 5A and B). PbΔp52/p36 sporozoite invasion followed similar kinetics to those observed for PbGFP sporozoites upon blockage of SR-BI or CD81, respectively, and was not modified by addition of anti-SRBI or anti-CD81 antibodies. Using antibodies specific for UIS4, a marker of the PV membrane (PVM) that specifically labels productive vacuoles (Risco-Castillo et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2005), we confirmed that PbGFP but not PbΔp52/p36 parasites could form replicative PVs, in both HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 5C). In both cell types, only very low numbers of EEFs were observed with PbΔp52/p36 parasites (Figure 5D), all of which were seemingly intranuclear and lacked a UIS4-labeled PVM (Figure 5E). We have shown before that intranuclear EEFs result from cell traversal events (Silvie et al., 2006a). Altogether these data demonstrate that PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites fail to productively invade host cells, irrespective of the entry route. Similar results were obtained with a P. berghei Δp36 single knockout line using the GOMO strategy (Figure 5—figure supplement 3). PbΔp36 sporozoites did not invade HepG2 cells or HepG2/CD81 cells, reproducing a similar phenotype as PbGFP parasites in the presence of anti-CD81 and anti-SR-BI neutralizing antibodies (Figure 5—figure supplement 4).

The 6-cys proteins P52 and P36 are required for productive host cell invasion.

(A–B) HepG2 (A) or Hepa1-6 cells (B) were incubated with PbGFP (blue lines) or PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites (red lines) for 15–120 min, in the presence (dotted lines) or absence (solid lines) of anti-SR-BI (A) or anti-CD81 (B) antibodies. Cells were then trypsinized and directly analyzed by FACS to quantify invaded (GFP-positive) cells. (C) HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells were infected with PbGFP or PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites and the number of EEFs was determined 28 hr post-infection by fluorescence microscopy. (D) HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells infected with PbGFP or PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites were fixed at 28 hr post-infection, stained with anti-UIS4 antibodies (red) and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (blue), and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Parasites were detected based on GFP expression (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) Quantification of UIS4 expression in HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells infected with PbGFP (red) or PbΔp52/p36 (black). (F) HepG2 (dotted lines) and HepG2/CD81 cells (solid lines) were incubated with PyGFP (blue lines) or PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites (red lines) for 15–180 min, trypsinized, and directly analyzed by FACS to quantify invaded (GFP-positive) cells. (G) HepG2/CD81 cells were infected with PyGFP or PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites and the number of EEFs was determined 24 hr post-infection by fluorescence microscopy. (H) HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells infected with PyGFP or PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites were fixed at 24 hr post-infection, stained with anti-UIS4 antibodies (red) and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (blue), and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Parasites were detected based on GFP expression (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (I) Quantification of UIS4 expression in HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells infected with PyGFP (red) or PyΔp52/p36 (black).

We then examined the kinetics of P. yoelii Δp52/p36 sporozoite invasion, in comparison to those of PyGFP sporozoites, in HepG2/CD81 versus HepG2 cells. PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites showed a lack of productive invasion in HepG2/CD81 cells, reproducing the invasion kinetics of PyGFP in the CD81-null HepG2 cells (Figure 5F). The PyΔp52/p36 mutant failed to form PV in HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 5G), where only intranuclear EEFs lacking a UIS4-labeled PVM were observed, similarly to the control PyGFP parasites in HepG2 cells (Figure 5H and I).

Altogether, these results reveal that P52 and P36 are required for sporozoite productive invasion, in both P. berghei and P. yoelii, irrespective of the entry route.

P36 is a key determinant of host cell receptor usage during sporozoite invasion

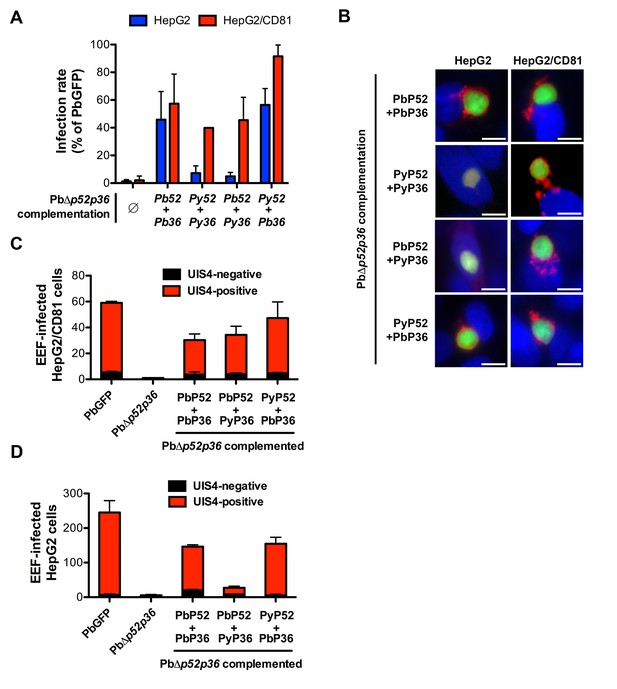

We further sought to investigate whether P52 and/or P36 proteins contribute to the selective usage of host cell receptors by different sporozoite species. We designed a trans-species genetic complementation strategy in which copies of P. berghei (Pb), P. yoelii (Py), P. falciparum (Pf) or P. vivax (Pv) P52 and P36 were introduced in the Δp52/p36 parasites. For this purpose, we used centromeric plasmid constructs for stable expression of the transgenes from episomes (Iwanaga et al., 2010). Complementing PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites with PbP52 and PbP36 restored sporozoite infectivity to both HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 6A), where the parasite formed UIS4-positive vacuoles (Figure 6B, C and D), confirming that genetic complementation was efficient. Remarkably, complementation of PbΔp52/p36 with PyP52 and PyP36 restored infection in HepG2/CD81 but not in HepG2 cells (Figure 6A), where only low numbers of UIS4-negative intranuclear EEFs were observed (Figure 6B and D). Thus, the concomitant replacement of PbP52 and PbP36 by their P. yoelii counterparts reproduced a P. yoelii-like invasion phenotype in chimeric P. berghei sporozoites, indicating that P52 and/or P36 contribute to the selective usage of a CD81-independent entry pathway in P. berghei sporozoites. Complementation of PbΔp52/p36 parasites with either P. falciparum or P. vivax P52 and P36 coding sequences did not restore infectivity of transgenic sporozoites, not only in HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A), but also in primary human hepatocytes, the most permissive cellular system for human malaria sporozoites in vitro (Figure 6—figure supplement 1B). Hence it was not possible using this approach to assess the function of P. falciparum or P. vivax P52 and P36 in transgenic P. berghei sporozoites.

P36 mediates CD81-independent entry in P. berghei sporozoites.

(A) HepG2 (blue histograms) or HepG2/CD81 cells (red histograms) were incubated with sporozoites from PbΔp52/p36 parasites genetically complemented with P. berghei and/or P. yoelii P52 and P36, and analysed by FACS or fluorescence microscopy to determine the number of GFP-positive cells 24 hr post-infection. Results from three independent experiments are shown and are expressed as the percentage of infection in comparison to control PbGFP-infected cultures (mean ±SD). (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of UIS4 expression in HepG2 or HepG2/CD81 cells infected with genetically complemented PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites. Cells were fixed with PFA 28 hr post-infection, permeabilized, and stained with anti-UIS4 antibodies (red) and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (blue). Parasites were detected based on GFP expression (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (C–D) HepG2/CD81 (C) and HepG2 (D) cells were infected with PbGFP, PbΔp52/p36 and complemented PbΔp52/p36 sporozoites. The numbers of UIS4-positive (red histograms) and UIS4-negative (black histograms) EEFs were determined by fluorescence microscopy 24 hr post-infection.

We next dissected the individual contribution of P52 and P36 by complementing PbΔp52/p36 parasites with mixed combinations of either PyP52 and PbP36 or PbP52 and PyP36. This approach revealed that P36 determines the ability of P. berghei sporozoites to enter cells via a CD81-independent route. Indeed, PbΔp52/p36 complemented with PyP52 and PbP36 infected both HepG2/CD81 and HepG2 cells (Figure 6A), forming UIS4-labeled PVs in both cell types (Figure 6B, C and D). P52 therefore is not responsible for the phenotypic difference between P. berghei and P. yoelii. In sharp contrast, complementation of PbΔp52/p36 with PbP52 and PyP36 restored sporozoite infectivity to HepG2/CD81 but not HepG2 cells, thus reproducing a P. yoelii-like invasion phenotype (Figure 6A, B and D).

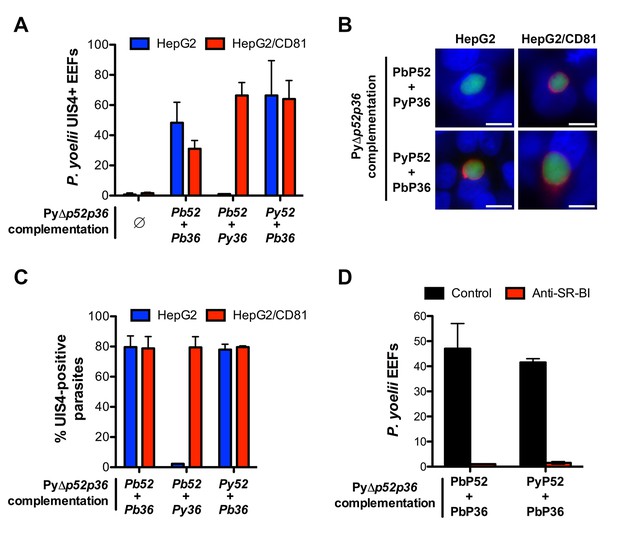

In reciprocal experiments, we analysed whether expression of PbP36 would be sufficient to allow P. yoelii sporozoites to invade CD81-null cells. For this purpose, we performed genetic complementation experiments in PyΔp52/p36 parasites, using the same constructs employed with the P. berghei mutant. Strikingly, whilst HepG2 cells are normally refractory to P. yoelii productive invasion, complementation with P. berghei P52 and P36 protein was sufficient to confer chimeric P. yoelii mutants the capacity to infect HepG2 cells (Figure 7A). Most importantly, PyΔp52/p36 parasites complemented with PyP52 and PbP36 infected both HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 cells (Figure 7A). In particular, PyΔp52/p36 parasites expressing PbP36 became capable of forming UIS4-positive PVs in HepG2 cells (Figure 7B). Thus, the transgenic expression of PbP36 appears to be sufficient to recapitulate a P. berghei-like invasion phenotype in P. yoelii sporozoites. In contrast, complementation of PyΔp52/p36 parasites with PbP52 and PyP36 restored sporozoite infectivity in HepG2/CD81 cells only, but not in HepG2 cells (Figure 7A and B). This confirms that P52, although essential for sporozoite entry, is not directly associated with host receptor usage. Finally, invasion of PbP36-expressing PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites was abrogated by anti-SR-BI antibodies in HepG2 cells (Figure 7C), demonstrating that P. berghei P36 is a key determinant of CD81-independent entry via SR-BI.

Transgenic P. yoelii sporozoites expressing PbP36 can infect CD81-null cells via SR-BI.

(A) HepG2 (blue) and HepG2/CD81 cells (red) were incubated with genetically complemented PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites, and fixed 24 hr post-infection. The number of UIS4-positive vacuoles was then determined by immunofluorescence. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of UIS4 expression in HepG2 or HepG2/CD81 cells infected with sporozoites of PyΔp52/p36 parasites genetically complemented with P52 and P36 from P. berghei or P. yoelii. Cells were fixed with PFA, permeabilized, and stained with anti-UIS4 antibodies (red) and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (blue). Parasites were detected based on GFP expression (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of UIS4 expression in HepG2 (blue) and HepG2/CD81 cells (red) infected with genetically complemented PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites and processed as in B for immunofluorescence. (D) HepG2 cells were incubated with PyΔp52/p36 sporozoites complemented with PbP36 and either PbP52 or PyP52, in the presence or absence of anti-SR-BI antibodies. Infected cultures were fixed 24 hr post-infection, and the number of EEFs was then determined by fluorescence microscopy.

Discussion

Until now, the nature of the molecular interactions mediating Plasmodium sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes has remained elusive. Previous studies have identified CD81 and SR-BI as important host factors for infection of hepatocytes (Silvie et al., 2003; Yalaoui et al., 2008a; Rodrigues et al., 2008). Still, the relation between CD81 and SR-BI and their contribution to parasite entry was unclear (Silvie et al., 2007; Foquet et al., 2015), and, importantly, parasite factors associated with CD81 or SR-BI usage had not been identified. Here we demonstrate that CD81 and SR-BI define independent entry pathways for sporozoites, and identify the parasite protein P36 as a critical parasite factor that determines host receptor usage during hepatocyte infection.

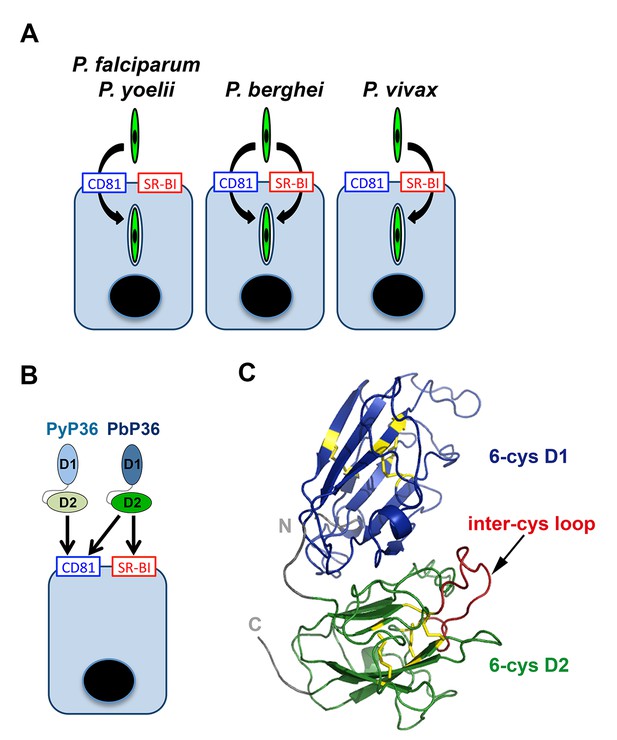

Our data provide molecular insights into the host entry pathways used by different sporozoite species (Figure 8A). We show that P. falciparum, like P. yoelii, relies on CD81 but not SR-BI, in agreement with the recent observation that antibodies against CD81 but not anti-SR-BI induce protection in humanized mice infected with P. falciparum (Foquet et al., 2015). Our results are also consistent with the study from Yalaoui et al. showing that in primary mouse hepatocytes antibodies against SR-BI do not inhibit P. yoelii infection when co-incubated together with sporozoites (Yalaoui et al., 2008a). In the same study, the authors proposed a model where SR-BI indirectly contributes to P. yoelii infection through regulation of membrane cholesterol and CD81 expression, however our data in the HepG2/CD81 cell model with both P. yoelii and P. berghei clearly rule out a role of SR-BI during CD81-dependent sporozoite entry. For the first time, we also analysed the role of host factors during P. vivax sporozoite infection. We found that, in contrary to P. falciparum, antibodies against SR-BI but not against CD81 inhibit infection of primary human hepatocyte cultures by P. vivax sporozoites, illustrating that the two main species causing malaria in humans use distinct routes to infect hepatocytes.

Model of host cell entry pathways for Plasmodium sporozoites.

(A) Host cell membrane proteins CD81 and SR-BI define two independent entry routes for Plasmodium sporozoites. P. falciparum and P. yoelii sporozoites require CD81 for infection, whereas P. vivax sporozoites infect hepatocytes using SR-BI. P. berghei sporozoites can enter cells alternatively via CD81 or SR-BI. (B) The 6-cysteine domain protein P36 determines host cell receptor usage during P. yoelii and P. berghei sporozoite invasion. Whilst PyP36 supports only CD81-dependent sporozoite entry, PbP36 mediates sporozoite invasion through both CD81- and SR-BI-dependent pathways. (C) Model of the 3D structure of P. berghei P36, established based on the crystal structure of PfP12 (2YMO). In the ribbon diagram, the tandem 6-cysteine domains are shown in blue (D1) and green (D2), respectively, and the cysteine residues and disulphide bonds in yellow. The loop located between the third and fourth cysteine residues of the D2 domain (inter-cys loop) is indicated in red.

SR-BI and CD81 both have been shown to bind the HCV envelope glycoprotein E2 (Pileri et al., 1998; Scarselli et al., 2002; Bartosch et al., 2003), and act in a sequential and cooperative manner to mediate virus entry (Kapadia et al., 2007), together with several additional entry factors (Colpitts and Baumert, 2016; Evans et al., 2007; Ploss et al., 2009). By contrast, as shown here, SR-BI and CD81 operate independently during Plasmodium sporozoite infection. Remarkably, P. berghei can use alternatively CD81 or SR-BI to infect cells, which is surprising given that CD81 and SR-BI are structurally unrelated. CD81 belongs to the family of tetraspanins, which are notably characterized by their propensity to dynamically interact with other membrane proteins and organize tetraspanin-enriched membrane microdomains (Charrin et al., 2014). CD81 might play an indirect role during Plasmodium sporozoite entry, possibly by interacting with other host receptors within these microdomains (Silvie et al., 2006b; Charrin et al., 2009a, 2009b). Interestingly, SR-BI is structurally related to CD36 (Neculai et al., 2013), which is known to bind several Plasmodium proteins, including P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) in the context of cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes to endothelial cells (Baruch et al., 1996; Oquendo et al., 1989; Barnwell et al., 1989). CD36 was also reported to interact with P. falciparum sequestrin (also called LISP2) (Ockenhouse et al., 1991), a member of the 6-cys protein family involved in parasite liver stage development (Orito et al., 2013; Annoura et al., 2014), and is a major determinant of P. berghei asexual blood stage sequestration (Franke-Fayard et al., 2005). CD36 was shown to be dispensable for mouse hepatocyte infection by P. yoelii and P. berghei sporozoites (Sinnis and Febbraio, 2002). However, it is conceivable that SR-BI, which shares a similar 3D structure as CD36 (Neculai et al., 2013), may interact with parasite proteins expressed by sporozoites, such as the 6-cys protein P36.

The 6-cys protein family is characterized by the presence of a cysteine-rich domain, the 6-cysteine (6-cys) or s48/45 domain. Plasmodium spp. possess a dozen 6-cys proteins, which perform important functions in different life cycle stages, and are often located on the parasite surface, consistent with a role in cellular interactions (Annoura et al., 2014). Previous studies have shown that Plasmodium P52 and P36 are crucial for infection of the liver by sporozoites (van Dijk et al., 2005; Ishino et al., 2005; van Schaijk et al., 2008), although it remained unclear whether their role was at the sporozoite entry step (Ishino et al., 2005; Labaied et al., 2007) or for maintenance of the PV post-entry (van Dijk et al., 2005; VanBuskirk et al., 2009; Mikolajczak et al., 2014). It should be noted that standard invasion assays, as performed in these studies, do not distinguish between sporozoite productive entry and non-productive invasion events associated with cell traversal, complicating the interpretation of phenotypic analysis of the mutants. Here, using GFP-expressing p52 and p36 mutants and a robust FACS-based invasion assay (Risco-Castillo et al., 2015), we unequivocally establish that P. yoelii and P. berghei sporozoites lacking P52 and P36 efficiently migrate through cells but do not commit to productive invasion, reproducing the phenotype observed upon blockage of CD81 or SR-BI.

Using a trans-species genetic complementation strategy, we identified P36 as a crucial parasite determinant of host receptor usage. Our data, combined with previous studies (van Dijk et al., 2005; Ishino et al., 2005; van Schaijk et al., 2008; Kaushansky et al., 2015), demonstrate that both P36 and P52 are necessary for sporozoite infection of hepatocytes, irrespective of the invasion route used by the parasite. Our study now reveals that P36 but not P52 is responsible for the phenotypic differences between P. berghei and P. yoelii sporozoites regarding host cell entry pathways. Importantly, P. berghei P36 mediates sporozoite entry via either CD81 or SR-BI, whereas P. yoelii P36 only supports CD81-dependent invasion (Figure 8B). These results strongly suggest that PbP36 contains specific structural determinants that confer the ability of the protein to interact with SR-BI or SR-BI-dependent molecules. P. berghei and P. yoelii P36 proteins share 88% identity and 97% similarity in their amino acid sequence (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). Structural modelling of PbP36, using the crystal structure of the 6-cys protein PfP12 (Tonkin et al., 2013) as a template, shows a typical beta sandwich fold for each of the tandem 6-cysteine domains (Figure 8C). Most of the divergent residues between PbP36 and PyP36 are located in the second 6-cys domain (Figure 8—figure supplement 1), including in a loop located between the third and fourth cysteine residues. In this particular loop, PfP36 and PvP36 contain an inserted sequence of 21 and 3 amino acids, respectively, which may affect their binding properties and functions.

Single gene deletions of p52 or p36 result in similar phenotypes as p52/p36 double knockouts, suggesting that the two proteins act in concert (van Dijk et al., 2005; Ishino et al., 2005; van Schaijk et al., 2008; Labaied et al., 2007). In P. falciparum blood stages, the two 6-cys proteins P41 and P12 interact to form stable heterodimers on the surface of merozoites (Tonkin et al., 2013; Taechalertpaisarn et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2015). Whilst P12 is predicted to be GPI-anchored, P41 lacks a membrane-binding domain, similarly to P36. By analogy, we hypothesize that P36 may form heterodimers with other GPI-anchored 6-cys proteins, including P52. Our data show that complementation of PbΔp52/p36 parasites with P52 and P36 from P. falciparum or P. vivax does not restore sporozoite infectivity, supporting the idea that other yet unidentified parasite factors cooperate with P52 and P36 during invasion. In addition to P52 and P36, sporozoites express at least three other 6-cys proteins, B9, P12p and P38 (Lindner et al., 2013; Swearingen et al., 2016). Whereas gene deletion of p38 causes no detectable phenotypic defect in P. berghei (van Dijk et al., 2010), B9 has been shown to play a critical role during liver stage infection, not only in P. berghei but also in P. yoelii and P. falciparum (Annoura et al., 2014). Whether B9, P38 and P12p associate with P52 and/or P36 and contribute to sporozoite invasion still deserves further investigations.

Several 6-cys proteins have been implicated in molecular interactions with host factors. As mentioned above, sequestrin was reported to interact with CD36 (Ockenhouse et al., 1991), although the functional relevance of this interaction remains to be determined, as sequestrin is only expressed towards the end of liver stage development (Orito et al., 2013). Recent studies have shown that P. falciparum merozoites evade destruction by the human complement through binding of host factor H to the 6-cys protein Pf92 (Rosa et al., 2016; Kennedy et al., 2016). Pfs47 expressed by P. falciparum ookinetes plays a critical role in immune evasion in the mosquito midgut, by suppressing nitration responses that activate the complement-like system (Molina-Cruz et al., 2013; Ramphul et al., 2015). Pfs47 was proposed to act as a ‘key’ that allows the parasite to switch off the mosquito immune system by interacting with yet unidentified mosquito receptors (‘lock’) (Molina-Cruz et al., 2015). By analogy, based on our results, one could envisage P36 as a crucial determinant of a sporozoite ‘key’ that opens SR-BI and/or CD81-dependent ‘locks’ for entry into hepatocytes.

The function of P36 interaction with host cell receptors remains to be defined. P36 binding to SR-BI and/or CD81, either directly or indirectly, may participate in a signalling cascade that triggers rhoptry secretion and assembly of the moving junction, key events committing the parasite to host cell entry (Besteiro et al., 2011). Alternatively, P36 may induce signalling in the host cell by acting on SR-BI or other hepatocyte receptors. In this regard, Kaushansky et al. recently reported that sporozoites preferentially invade host cells expressing higher levels of the EphA2 receptor (Kaushansky et al., 2015). Interestingly, this preference was still observed with p52/p36-deficient parasites, strongly suggesting that there is no direct link between EphA2 and P52/P36-dependent productive invasion. However, the same study showed that P36 interferes with Ephrin A1-mediated EphA2 phosphorylation (Kaushansky et al., 2015), raising the possibility that P36 may affect EphA2 signalling indirectly, for example via SR-BI and the SRC pathway (Naudin et al., 2014; Mineo and Shaul, 2003).

In conclusion, our study reveals that host CD81 and SR-BI define two alternative pathways in human cells for sporozoite entry. Most importantly, we identified the parasite 6-cysteine domain protein P36 as a key determinant of host receptor usage during infection. These results pave the way toward the elucidation of the mechanisms of sporozoite invasion. The identification of the parasite ligands that mediate host cell entry may provide potential targets for the development of next-generation malaria vaccines. P36 is required for both CD81- and SR-BI-dependent sporozoite entry, suggesting that it may represent a relevant target in both P. falciparum and P. vivax. The understanding of host-parasite interactions may also contribute to novel therapeutic approaches. SR-BI-targeting agents have entered clinical development for prevention of HCV graft infection (Felmlee et al., 2016). Our data suggest that SR-BI-targeting strategies may be effective to prevent establishment of the liver stages of P. vivax, including the dormant hypnozoite forms.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals, parasites and cells

Request a detailed protocolWe used wild type P. berghei (ANKA strain, clone 15cy1) and P. yoelii (17XNL strain, clone 1.1), and GFP-expressing PyGFP and PbGFP parasite lines, obtained after integration of a GFP expression cassette at the dispensable p230p locus (Manzoni et al., 2014). P. berghei and P. yoelii blood stage parasites were propagated in female Swiss mice (6–8 weeks old, from Janvier Labs). Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were fed on P. berghei or P. yoelii-infected mice using standard methods (Ramakrishnan et al., 2013), and kept at 21°C and 24°C, respectively. P. berghei and P. yoelii sporozoites were collected from the salivary glands of infected mosquitoes 21–28 or 14–18 days post-feeding, respectively. A. stephensi mosquitoes infected with P. falciparum sporozoites (NF54 strain) were obtained from the Department of Medical Microbiology, University Medical Centre, St Radboud, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. P. vivax sporozoites were isolated from A. cracens mosquitoes, 15–21 days after feeding on blood from infected patients on the Thailand-Myanmar border, as described (Andolina et al., 2015). HepG2 (ATCC HB-8065), HepG2/CD81 (Silvie et al., 2006a) and Hepa1-6 cells (ATCC CRL-1830) were checked for the absence of mycoplasma contamination and cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics (Life Technologies), as described (Silvie et al., 2007). HepG2 and HepG2/CD81 were cultured in culture dishes coated with rat tail collagen I (Becton-Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France). Primary human hepatocytes were isolated and cultured as described previously (Silvie et al., 2004).

In vitro infection assays

Request a detailed protocolPrimary human hepatocytes (5 × 104 per well in collagen-coated 96-well plates) were infected with P. vivax or P. falciparum sporozoites (3 × 104 per well), as described (Silvie et al., 2004), and cultured for 5 days before fixation with cold methanol and immunolabeling of EEFs with antibodies specific for Plasmodium HSP70 (Tsuji et al., 1994). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies). Host cell invasion by GFP-expressing P. berghei and P. yoelii sporozoites was monitored by flow cytometry (Prudêncio et al., 2008). Briefly, hepatoma cells (3 × 104 per well in collagen-coated 96-well plates) were incubated with sporozoites (5 × 103 to 1 × 104 per well). At different time points, cell cultures were washed, trypsinized and analyzed on a Guava EasyCyte 6/2L bench cytometer equipped with a 488 nm laser (Millipore), for detection of GFP-positive cells. To assess liver stage development, HepG2 or HepG2/CD81 cells were infected with GFP-expressing sporozoites and cultured for 24–36 hr before analysis either by FACS or by fluorescence microscopy, after fixation with 4% PFA and staining with antibodies specific for UIS4 (Sicgen) and Hoechst 33342. For antibody-mediated inhibition assays, we used polyclonal antisera against human SR-BI raised after genetic immunization of rabbits and rats (Maillard et al., 2006; Zeisel et al., 2007), and monoclonal antibodies against human SR-BI (NK-8H5-E3) (Zahid et al., 2013), human CD81 (1D6, Abcam) or mouse CD81 (MT81)(Silvie et al., 2006b).

Small interfering RNA and plasmid transfection

Request a detailed protocolWe used small double stranded RNA oligonucleotides targeting human CD81 (5’-GCACCAAGTGCATCAAGTA-3’), human SR-BI (5’-GGACAAGTTCGGATTATTT-3’) or mouse CD81 (5’-CGTGTCACCTTCAACTGTA-3’). An irrelevant siRNA oligonucleotide targeting human CD53 (5’-CAACTTCGGAGTGCTCTTC-3’) was used as a control. Transfection of siRNA oligonucleotides was performed by electroporation, as described (Silvie et al., 2006a). Following siRNA transfection, cells were cultured for 48 hr before flow cytometry analysis or sporozoite infection. Transfection of pcDNA3 plasmids encoding human CD81 (Yalaoui et al., 2008b) or SR-BI (Maillard et al., 2006) was performed 24 hr after siRNA using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Following plasmid transfection, cells were cultured for an additional 24 hr before sporozoite infection.

Constructs for targeted gene deletion of p52 and p36

Request a detailed protocolPbΔp52p36 and PbΔp36 mutant parasites were generated using a 'Gene Out Marker Out’ strategy (Manzoni et al., 2014). For generation of PbΔp52p36 parasites, a 5’ fragment of PbP52 gene (PBANKA_1002200) and a 3’ fragment of PbP36 gene (PBANKA_1002100) were amplified by PCR from P. berghei ANKA WT genomic DNA, using primers PbP52rep1for (5’-TCCCCGCGGAATCGTGATGCTATGGATAACGTAACAC-3’), PbP52rep2rev (5’-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCAAAAAGAGACAAACACACTTTGTGAACACC-3’), PbP36rep3for (5’-CCGCTCGAGTTAATATGTGATGTGTGTAGAAGAGTGAGG-3’) and PbP36rep4rev (5’-GGGGTACCTTGATATACATGCAACTTTTCACATAGG-3’), and inserted into SacII/NotI and XhoI/KpnI restriction sites, respectively, of the GOMO-GFP vector. For generation of PbΔp36 parasites, a 5’ and a 3’ fragment of PbP36 gene were amplified by PCR from P. berghei ANKA WT genomic DNA, using primers PbP36repAfor (5’-AGCTGGAGCTCCACCGCGGGAAAAAAGGTTAACACATATATTGAAAAGC-3’), PbP36rep-Arev (5’-CGGCTGAGGGCGGCCGCAATCAAAAAAAATAATAAAAACAAATATATGTACACTCG-3’), and PbP36repBfor (5’-ATTAATTTCACTCGAGTATGTGATGTGTGTAGAAGAGTGAGG-3’) and PbP36repBrev (5’-TATAGGGCGAATTGGGTACCGCACGCCGGAAAAATTACAATACAAATGG-3’), and inserted into SacII/NotI and XhoI/KpnI restriction sites, respectively, of the GOMO-GFP vector using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech).

For generation of PyΔp52p36 parasites, 5’ and 3’ fragments of PyP52 gene (PY17X_1003600) and a 3’ fragment of PyP36 gene (PY17X_1003500) were amplified by PCR from P. yoelii 17XNL WT genomic DNA, using primers PyP52rep1for (5’-TCCCCGCGGAATCGCCATGCTATGGATAGTGTAGC-3’), PyP52rep2rev (5’-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCCATTGAAGGGGGGAACAAATCGACG-3’), PyP52rep3for (5’-CCGCTCGAGTCAATATATGCCCACTATTCGAATTTTTGG-3’), PyP52rep4rev (5’-GGGGTACCTTATTGATATGCATGCAACTTTCACATAGG-3’), PyP36repFor (5’-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCAAAATGCAAGGCGCCCGTTTAGAACC-3’) and PyP36repRev (5’-CCGGAATTCACAAAAAGATGCTACTGTGAAAAGCTCACC-3’). The fragments were inserted into SacII/NotI, XhoI/KpnI and NotI/EcoRI restriction sites, respectively, of a GOMO vector backbone containing mCherry and hDHFR-yFCU cassettes. The resulting targeting constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (GATC Biotech), and were linearized with SacII and KpnI before transfection.

Wild type P. berghei ANKA blood stage parasites were transfected with pbp52p36 and pbp36 targeting constructs using standard transfection methods (Janse et al., 2006). GFP-expressing parasite mutants were isolated by flow cytometry after positive and negative selection rounds, as described (Manzoni et al., 2014). PyGFP blood stage parasites were transfected with a pyp52pyp36 targeting construct and a GFP-expressing drug selectable marker-free PyΔp52p36 mutant line was obtained using a two steps ‘Gene Out Marker Out’ strategy. Correct construct integration was confirmed by analytical PCR using specific primer combinations.

Constructs for genetic complementation of Δp52p36 mutants

Request a detailed protocolFor genetic complementation experiments, we used centromeric plasmids to achieve stable transgene expression from episomes (Iwanaga et al., 2010). Complementation plasmids were obtained by replacing the GFP cassette of pCEN-SPECT2 plasmid (kindly provided by Dr S. Iwanaga) with a P52/P36 double expression cassette. Four complementing plasmids were generated, allowing expression of PbP52/PbP36, PyP52/PyP36, PbP52/PyP36 or PyP52/PbP36.

The centromeric plasmid constructs were assembled by In-Fusion cloning of 4 fragments in two-steps, into KpnI/SalI restriction sites of the pCEN-SPECT2 plasmid. For this purpose, fragments corresponding to the promoter region of PbP52 (insert A, 1.5 kb), the open reading frame (ORF) of PbP52 (insert B, 1.7 kb), the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of PbP52 and promoter region of PbP36 (insert C, 1.5 kb), the ORF and 3’ UTR of PbP36 (insert D, 2 kb), the promoter region of PyP52 (insert E, 1.5 kb), the open reading frame (ORF) of PyP52 (insert F, 1.7 kb), the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of PyP52 and promoter region of PyP36 (insert G, 1.6 kb), and the ORF and 3’ UTR of PyP36 (insert H, 2 kb) were first amplified by PCR from P. berghei or P. yoelii WT genomic DNA, using the following primers: Afor (5’-TATAGGGCGAATTGGGTACCTTCACATGCATAAACCCGAAGTGTGC-3’), Arev (5’-GAAAAAAGCAGCTAGCTTGCTTTAATGTAGAAAAAATATTTATGGATTTGG-3’), Bfor (5’-ATTAAAGCAAGCTAGCAATATTACATTTGTGGTAAGGTAAAAC-3’), Brev (5’-GAAGAGGTACCAAAAAGGTTTTGCCAAAATG-3’), Cfor (5’-TTTTGGTACCTCTTCTTCTTATTATGAGG-3’), Crev (5’-GAAAAAAGCAGCTAGCAGAAAGAAACAACAGTTATCGTAATAAAG-3’), Dfor (5’-GCTAGCTGCTTTTTTCTTGAATCGACAATTATAATACTGAGGC-3’), Drev (5’-TACAAGCATCGTCGACATTGCCATTACAATATGCTATAATCTG-3’), Efor (5’-TATAGGGCGAATTGGGTACCTGCACATGCATAAACTCGAAGTGTGC-3’), Erev (5’-AAAAAAGCAGCTAGCTTGCTTTAATGTAGAAAAAATATTTATGTATTTGG-3’), Ffor (5’-ATTAAAGCAAGCTAGAATATTGCATTTGTGGTAAGGCAAATC-3’), Frev (5’-GAAGACGTACCAAACATATTTTGCCAAAATG-3’), Gfor (5’-GTTTGGTACGTCTTCTTCTTATTATGAGG-3’), Grev (5’-GAAAAAAGCAGCTAGGATAACTGTCGATTCAAAGAAACAACC-3’), Hfor (5’-GCTAGCTGCTTTTTTATACTTGAAGCATTTTTGTTGACTCTACC-3’), Hrev (5’-TACAAGCATCGTCGACATTACCATTACGATATGCTATAATCTG-3’). Cloning of fragments A and D followed by B and C into the pCEN vector resulted in the PbP52/PbP36 complementation plasmid. Cloning of fragments E and H followed by F and G into the pCEN vector resulted in the PyP52/PyP36 complementation plasmid. Cloning of fragments A and D followed by F and G into the pCEN vector resulted in the PyP52/PbP36 complementation plasmid. Cloning of fragments E and H followed by B and C into the pCEN vector resulted in the PbP52/PyP36 complementation plasmid. The centromeric plasmids for expression of P. falciparum and P. vivax P52 and P36 were assembled by In-Fusion cloning of 5 fragments in two steps. For this purpose, fragments corresponding to the promoter region of PbP52 (insert B1, 1.9 kb), the 3’ UTR of PbP52 and promoter region of PbP36 (insert B2, 1.6 kb), the 3’ UTR of PbP36 (insert B3, 2 kb), the ORF of PfP52 (insert F1, 1.4 kb), the ORF of PfP36 (insert F2, 1.1 kb), the ORF of PvP52 (insert V1, 1.4 kb) and the ORF of PvP36 (insert V2, 1.1 kb), were first amplified by PCR from P. berghei, P. falciparum or P. vivax genomic DNA, using the following primers: B1for (5’-tatagggcgaattgggtaccTTCACATGCATAAACCCGAAGTGTGC-3’), B1rev (5’-gctagcTTACTATTATTCTCAAAATGTGTATCACATTG-3’), B2for (5’-ATCACAATATGTGCATAGTGTCAATATGCC-3’), B2rev (5’-AATCAAAAAAAATAATAAAAACAAATATATGTACACTCG-3’), B3for (5’-TAATAGTAAgctagcTATGTGATGTGTGTAGAAGAGTGAGGGAG-3’), B3rev (5’-tacaagcatcgtcgacATTGCCATTACAATATGCTATAATCTG-3’), F1for (5’-ATAATAGTAAgctagcAAAATGTATGTATTGGTGCTTATTCATATGTG-3’), F1rev (5’-TGCACATATTGTGATTTATGTTGAATATATATATATTAAAAATATGAATAATATTAAG-3’), F2for (5’-TTATTTTTTTTGATTATGGCTTATAATATTTGGGAGGAATATATAATGG-3’), F2rev (5’-ACATCACATAgctagcCTAACTTTCTACAGTTTTATTTATGTTAAATAAACC-3’), V1for (5’-ATAATAGTAAgctagcAAAATGAGGCGGATTCTGCTGGGCTGCTTGG-3’), V1rev (5’-TGCACATATTGTGATTTACAGGGACGAGAAACCCGCGTAG-3’), V2for (5’-TTATTTTTTTTGATTATGAGCACATGCCTTCCAGTAGTGTGG-3’), and V2rev (5’-ACATCACATAgctagcTCACACCGCTTCAACCGCTGCG-3’). An intermediate vector was first assembled by cloning inserts B1 and B3 into KpnI/SalI restriction sites of the pCEN-SPECT2 plasmid. Subsequently, In-Fusion cloning of inserts F1, B2 and F2 or inserts V1, B2 and V2 into the NheI restriction site of the intermediate vector resulted into PfP52/PfP36 and PvP52/PvP36 expression centromeric plasmids, respectively. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (GATC Biotech) before transfection.

Parasite transfection and selection

Request a detailed protocolFor double crossover replacement of P52 and P36 genes and generation of the PbΔp52p36, PbΔp36 and PyΔp52p36 parasite lines, purified schizonts of wild type P. berghei ANKA or PyGFP were transfected with 5–10 μg of linearized construct by electroporation using the AMAXA NucleofectorTM device (program U33), as described elsewhere (Janse et al., 2006), and immediately injected intravenously in the tail of one mouse. The day after transfection, pyrimethamine (70 or 7 mg/L for P. berghei and P. yoelii, respectively) was administrated in the mouse drinking water, for selection of transgenic parasites. Pure transgenic parasite populations were isolated by flow cytometry-assisted sorting of GFP and mCherry-expressing blood stage parasites on a FACSAria II (Becton-Dickinson), transferred into naïve mice, treated with 1 mg/ml 5-fluorocytosine (Meda Pharma) in the drinking water, and sorted again for selection of GFP+ parasites only, as described (Manzoni et al., 2014). In the case of the PyΔp52p36 mutant, GFP+ mCherry+ recombinant parasites were first cloned by injection of limiting dilutions into mice prior to the negative selection step. For genetic complementation of the mutants, purified schizonts of PbΔp52p36 and PyΔp52p36 parasites were transfected with 5 μg of centromeric plasmids, followed by positive selection of transgenic parasites with pyrimethamine, as described above.

Parasite genotyping

Request a detailed protocolParasite genomic DNA was extracted using the Purelink Genomic DNA Kit (Invitrogen), and analysed by PCR using primer combinations specific for WT and recombined loci. For genotyping of PbΔp52p36 parasites, we used primer combinations specific for the WT Pbp52 locus (5’-AATGAGATGTCAAAAAATATAGTGCTTCC-3’ and 5’-AAATGAGCAGTTTCTTCTACGTTGTTTCC-3’), for the 5’ region of the recombined locus (5’-TATGTTTGGAATATCAGGACAAGGCATGG-3’ and 5’-TAATAATTGAGTCTTTAGTAACGAATTGCC-3’), and for the 3’ region of the recombined locus before (5’-ATCGTGGAACAGTACGAACGCGCCGAGG-3’ and 5’-ATTGGACGTTTATTATTATTGCAAAAGCG-3’) or after excision of the selectable marker (5’-GATGGAAGCGTTCAACTAGCAGACC-3’ and 5’-ATTGGACGTTTATTATTATTGCAAAAGCG-3’). For genotyping of PbΔp36 parasites, we used primer combinations specific for the WT Pbp36 locus (5’-GAGTTCGCACGCCATATTAACACG-3’ and 5’-CCATGATGAGATGCTAAATCGGG-3’), for the 5’ region of the recombined locus (5’-GGAAGCATCATACAAAAAAGAAAGC-3’ and 5’-TAATAATTGAGTCTTTAGTAACGAATTGCC-3’), and for the 3’ region of the recombined locus before (5’-ATCGTGGAACAGTACGAACGCGCCGAGG-3’ and 5’-CGTTATCTCTTTTTTTACTCATTAAGTATTG-3’) or after excision of the selectable marker (5’-GATGGAAGCGTTCAACTAGCAGACC-3’ and 5’-CGTTATCTCTTTTTTTACTCATTAAGTATTG-3’). For genotyping of PyΔp52p36 parasites, we used primer combinations specific for the WT PyP52 locus (5’-ACTATATTTCAATTGGAGACATGTGG-3’ and 5’-ATGCAAAAAAAAGTTATCATTGCTAGTTGG-3’), for the 5’ region of the recombined locus (5’-GTATGTTTGGAATGCCAGGATATGACATGG-3’ and 5’-CCGGAATTCACAAAAAGATGCTACTGTGAAAAGCTCACC-3’), and for the 3’ region of the recombined locus before (5’-AGTTACACGTATATTACGCATACAACGATG-3’ and 5’-TAAGCATATATTGTATATTTGCCTTGTCC-3’) or after excision of the selectable marker (5’-GTATGTTTGGAATGCCAGGATATGACATGG-3’ and 5’-AATCTGATATGATAAATTATGGTATTGGAC-3’).

Bioinformatic and structural analysis

Request a detailed protocolAmino-acid sequences of the P36 proteins from P. falciparum (379 aa, gi:296004390, PF3D7_0404400), P. vivax (320 aa, gi:156094683, PVX_001025), P. berghei (352 aa, gi:991456178, PBANKA_1002100) and P. yoelii (356 aa, gi:675237743, PY17X_1003500) were obtained from Genbank. Sequence alignments were carried out using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). A 3D model of P. berghei P36 was generated by the prediction program I-Tasser (Yang et al., 2015), using the 3D structure of Pf12 (Pf12short in ref [Tonkin et al., 2013]), which contains two 6-cys domains D1 and D2 arranged in tandem, as a template (PDB access code 2YMO). The 3D model for PbP36 was then superimposed to the template Pf12short and visually inspected using the program Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), and the rotamers for the Cys residues adjusted such that the three disulfides bonds for each domain were formed following the pattern C1-C2, C3-C6 and C4-C5.

Statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolStatistical significance was assessed by non-parametric analysis using the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. All statistical tests were computed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Significance was defined as p<0.05 (ns, statistically non-significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01). In vitro experiments were performed at least three times, with a minimum of three technical replicates per experiment.

Ethics statement

Request a detailed protocolAll animal work was conducted in strict accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and Council ‘On the protection of animals used for scientific purposes’. The protocol was approved by the Charles Darwin Ethics Committee of the University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France (permit number Ce5/2012/001). Blood samples were obtained from P. vivax-infected individuals attending the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) clinics on the western Thailand-Myanmar border, after signature of a consent form (Andolina et al., 2015). Primary human hepatocytes were isolated from healthy parts of human liver fragments, which were collected from adult patients undergoing partial hepatectomy (Service de Chirurgie Digestive, Hépato-Bilio-Pancréatique et Transplantation Hépatique, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France). The collection and use of this material were undertaken in accordance with French national ethical guidelines under Article L. 1121–1 of the ‘Code de la Santé Publique’, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Comité de Protection des Personnes) of the Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France.

References

-

Host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites: the junction conundrumPLoS Pathogens 10:e1004273–1004279.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004273

-

Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptorJournal of Biological Chemistry 278:41624–41630.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M305289200

-

The moving junction of apicomplexan parasites: a key structure for invasionCellular Microbiology 13:797–805.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01597.x

-

The Major CD9 and CD81 molecular partner. identification and characterization of the complexesThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 276:14329–14337.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M011297200

-

Lateral organization of membrane proteins: tetraspanins spin their webBiochemical Journal 420:133–154.https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20082422

-

The ig domain protein CD9P-1 down-regulates CD81 ability to support plasmodium yoelii infectionJournal of Biological Chemistry 284:31572–31578.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.057927

-

Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphicsActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 60:2126–2132.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444904019158

-

New perspectives for preventing hepatitis C virus liver graft infectionThe Lancet Infectious Diseases 16:735–745.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00120-1

-

Anti-CD81 but not anti-SR-BI blocks plasmodium falciparum liver infection in a humanized mouse modelJournal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 70:1784–1787.https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv019

-

Malaria circumsporozoite protein binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans associated with the surface membrane of hepatocytesJournal of Experimental Medicine 177:1287–1298.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.177.5.1287

-

Recruitment of factor H as a Novel Complement Evasion Strategy for Blood-Stage plasmodium falciparum infectionThe Journal of Immunology 196:1239–1248.https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1501581

-

Total and putative surface proteomics of malaria parasite salivary gland sporozoitesMolecular & Cellular Proteomics 12:1127–1143.https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M112.024505

-

HDL stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a novel mechanism of HDL actionTrends in Cardiovascular Medicine 13:226–231.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1050-1738(03)00098-7

-

Looking under the skin: the first steps in malarial infection and immunityNature Reviews Microbiology 11:701–712.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3111

-

Laboratory maintenance of rodent malaria parasitesMethods in Molecular Biology 923:51–72.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-62703-026-7_5

-

Malaria sporozoites Traverse Host cells within transient vacuolesCell Host & Microbe 18:593–603.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.006

-

CD81 is required for rhoptry discharge during host cell invasion by plasmodium yoelii sporozoitesCellular Microbiology 16:1533–1548.https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12309

-

Alternative invasion pathways for plasmodium berghei sporozoitesInternational Journal for Parasitology 37:173–182.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.10.005

-

A role for apical membrane antigen 1 during invasion of hepatocytes by plasmodium falciparum sporozoitesJournal of Biological Chemistry 279:9490–9496.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M311331200

-

Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites infect CD36-deficient miceExperimental Parasitology 100:12–16.https://doi.org/10.1006/expr.2001.4676

-

Demonstration of heat-shock protein 70 in the sporozoite stage of malaria parasitesParasitology Research 80:16–21.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00932618

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

European Commission

- Dominique Mazier

- Thomas F Baumert

- Olivier Silvie

Agence Nationale de la Recherche

- Mirjam B Zeisel

- Dominique Mazier

- Thomas F Baumert

- Olivier Silvie

National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research

- Olivier Silvie

Conseil Régional, Île-de-France

- Giulia Manzoni

- Marion Gransagne

Wellcome

- François Nosten

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maurel Tefit, Thierry Houpert, Prapan Kittiphanakun and Saw Nay Hsel for rearing of mosquitoes in Paris and at SMRU; Geert-Jan van Gemert and Robert W Sauerwein for providing P. falciparum-infected mosquitoes; Bénédicte Hoareau-Coudert (Flow Cytometry Core CyPS) for parasite sorting by flow cytometry; Valérie Soulard, Audrey Lorthiois and Morgane Mitermite for technical assistance; Maryse Lebrun for critically reading the manuscript; and Shiroh Iwanaga for kindly providing the pCEN-SPECT2 plasmid. This work was funded by the European Union (FP7 Marie Curie grant PCIG10-GA-2011–304081, FP7 PathCo Collaborative Project HEALTH-F3-2012-305578, ERC-AdG-2014–671231-HEPCIR, FP7 HepaMab, and Interreg IV-Rhin Supérieur-FEDER Hepato-Regio-Net 2012, H2020-2015-667273-HEP-CAR), the Laboratoires d'Excellence ParaFrap and HepSYS (ANR-11-LABX-0024 and ANR-10-LABX-0028), and the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs, project grant NC/L000601/1). SMRU is part of the Mahidol-Oxford University Research Unit supported by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain. GM and MG were supported by a ‘DIM Malinf’ doctoral fellowship awarded by the Conseil Régional d'Ile-de-France.

Ethics

Human subjects: Blood samples were obtained from P. vivax-infected individuals attending the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) clinics on the western Thailand-Myanmar border, after signature of a consent form. Primary human hepatocytes were isolated from healthy parts of human liver fragments, which were collected from adult patients undergoing partial hepatectomy (Service de Chirurgie Digestive, Hépato-Bilio-Pancréatique et Transplantation Hépatique, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtriere, Paris, France). The collection and use of this material were undertaken in accordance with French national ethical guidelines under Article L. 1121-1 of the 'Code de la Santé Publique', and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Comité de Protection des Personnes) of the Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, France.

Animal experimentation: All animal work was conducted in strict accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and Council 'On the protection of animals used for scientific purposes'. The protocol was approved by the Charles Darwin Ethics Committee of the University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France (permit number Ce5/2012/001).

Copyright

© 2017, Manzoni et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 3,362

- views

-

- 798

- downloads

-

- 82

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 82

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25903

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Epidemiology and Global Health

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

eLife has published papers on many tropical diseases, including malaria, Ebola, leishmaniases, Dengue and African sleeping sickness.