Plant Pathology: Plasmid-powered evolutionary transitions

Many bacteria are closely associated with eukaryotic hosts. This relationship can be mutually beneficial, commensal (that is, it benefits one party without affecting the other), or pathogenic. Moreover, and perhaps surprisingly, there are many examples of pathogenic bacteria that are close relatives of mutualistic or commensal bacteria (Wood et al., 2001). For example, while most strains of E. coli are commensal, pathogenic strains – such as those that cause food poisoning – emerged from commensal ancestors (Pupo et al., 2000).

Historically, the bacterial genus Rhodococcus has been synonymous with pathogenesis because most described strains could cause a plant disease called leafy gall and stunt the growth of their plant hosts (Stes et al., 2011). Recently, it was found that some Rhodococcus strains are benign, and some are constituents of a healthy microbiome in plants (Bai et al., 2015; Hong et al., 2016). Now, in eLife, Jeff Chang of Oregon State University and co-workers – including Elizabeth Savory, Skylar Fuller and Alexandra Weisberg as joint first authors – report using a collection of Rhodococcus strains to study the molecular mechanisms that underlie distinct bacterial lifestyles (Savory et al., 2017).

Savory et al. isolated 60 strains of Rhodococcus bacteria from healthy and diseased plants from 16 nurseries over a period of several years and then sequenced their genomes and plasmids (which usually contain the virulence genes which make Rhodococcus pathogenic). The researchers compared pathogenic and commensal strains and used single nucleotide polymorphisms to reconstruct evolutionary histories within the Rhodococcus genus. They found relatively little correlation between the genome sequences of a strain and the DNA sequences in the plasmids. In particular, they found that isolates with similar genomes could have plasmids with radically different virulence genes, while plasmids with similar virulence genes could be found in strains with very different genomes. This suggests that the emergence of pathogenic strains may be driven by the transfer of plasmids between strains that are relatively evolutionarily distant from each other.

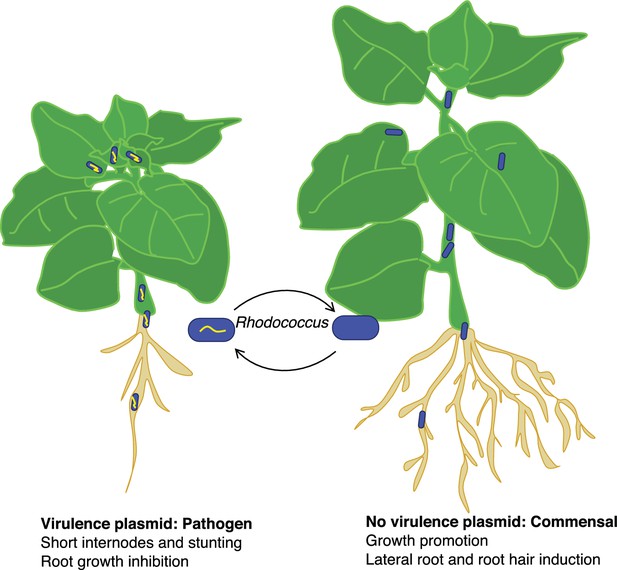

The researchers identified Rhodococcus isolates that lack a virulence plasmid but are close relatives of isolates that possess a plasmid. They showed that Rhodococccus isolates that lack a virulence plasmid can colonize Nicotiana benthamiana, a model plant that is susceptible to Rhodococcus infection. However, rather than causing disease, the strains lacking a virulence plasmid promoted the development of lateral roots and root hairs (Figure 1). This indicates that beneficial and pathogenic Rhodococcus are closely related, which led Savory et al. to hypothesize that the commensal and pathogenic Rhodococcus may evolve by the acquisition or loss of a virulence plasmid.

The good and bad sides of Rhodococcus.

The acquisition of a virulence plasmid (yellow) can transform benign commensal strains of Rhodococcus (blue) into pathogenic strains (blue and yellow) that stunt the growth of the plant and its roots (left) compared with a healthy plant (right). However, this process is reversible, and the loss of the virulence plasmid results in the bacteria becoming commensal again.

Savory et al. went on to experimentally demonstrate that pathogenic Rhodococcus strains can evolve from commensals. They showed that the introduction of a virulence plasmid from a pathogenic isolate into a beneficial strain was sufficient to cause disease in N. benthamiana. They also showed that the transition from commensal to pathogen is reversible: plasmid loss causes a virulent strain to become beneficial. By combining experimental data with genomic evidence, Savory et al. conclusively demonstrate that a readily transmissible plasmid is necessary and sufficient to reversibly transform beneficial Rhodococcus strains into pathogens.

Recently, it has been alleged that various strains of Rhodococcus are the cause of “pistachio bushy top syndrome” (PBTS), which has affected millions of pistachio trees in the United States and resulted in substantial economic losses (Stamler et al., 2015). However, rapid evolutionary changes present a challenge in identifying the pathogenic agents responsible for PBTS. Savory et al. tested the virulence of two Rhodococcus strains purported to be the causative agents of PBTS on several different hosts: they found that both isolates were not pathogenic. Moreover, they report that they were unable to amplify Rhodococcus virulence genes by PCR. This, combined with the fact that the published genomes of these strains do not contain virulence loci (Stamler et al., 2016), suggests that the plasmid was lost during isolation or that the disease was misdiagnosed.

The ambiguity of the cause of PBTS underscores the need for multiple independent methods that can verify the identity of an emerging plant pathogen, particularly when it has benign close relatives. To this end, Savory et al. developed an alternative method of identifying virulent strains of Rhodococcus based on recombinase polymerase amplification, and showed that this test could robustly discriminate between pathogenic and beneficial strains by targeting conserved loci in the virulence plasmid.

The work of Savory et al. provides insights into the evolutionary history of plant pathogens and mutualists. In particular, the coincidence of virulence and mutualism within the Rhodococcus clade suggests that both strategies are adaptive under certain conditions: sustained positive selection for one lifestyle would be unlikely to result in closely related strains with dramatically different effects on plant health. Building on this work may illuminate the evolutionary mechanisms that drive transitions from beneficial to pathogenic lifestyles in bacteria. This in turn could have profound implications for the management of emerging agricultural diseases and the evolution of plant-microbe interactions.

References

-

A leaf-inhabiting endophytic bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. kb6, enhances sweet potato resistance to black rot disease caused by Ceratocystis fimbriataJournal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 26:488–492.https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1511.11039

-

A successful bacterial coup d'état: how Rhodococcus fascians redirects plant developmentAnnual Review of Phytopathology 49:69–86.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095217

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2017, Melnyk et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,445

- views

-

- 169

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 3

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.33383