Evolutionary rescue of phosphomannomutase deficiency in yeast models of human disease

Abstract

The most common cause of human congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are mutations in the phosphomannomutase gene PMM2, which affect protein N-linked glycosylation. The yeast gene SEC53 encodes a homolog of human PMM2. We evolved 384 populations of yeast harboring one of two human-disease-associated alleles, sec53-V238M and sec53-F126L, or wild-type SEC53. We find that after 1000 generations, most populations compensate for the slow-growth phenotype associated with the sec53 human-disease-associated alleles. Through whole-genome sequencing we identify compensatory mutations, including known SEC53 genetic interactors. We observe an enrichment of compensatory mutations in other genes whose human homologs are associated with Type 1 CDG, including PGM1, which encodes the minor isoform of phosphoglucomutase in yeast. By genetic reconstruction, we show that evolved pgm1 mutations are dominant and allele-specific genetic interactors that restore both protein glycosylation and growth of yeast harboring the sec53-V238M allele. Finally, we characterize the enzymatic activity of purified Pgm1 mutant proteins. We find that reduction, but not elimination, of Pgm1 activity best compensates for the deleterious phenotypes associated with the sec53-V238M allele. Broadly, our results demonstrate the power of experimental evolution as a tool for identifying genes and pathways that compensate for human-disease-associated alleles.

Editor's evaluation

This valuable paper shows that experimental evolution can shed new and unbiased light on mutations involved in human diseases by showing how growth defects can be compensated. The evidence is convincing, benefiting from not only genetics but also well-established biochemical assays. This paper will be of interest to a broad group of evolutionary biologists and biologists interested in human diseases.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79346.sa0Introduction

Protein glycosylation is an important cotranslational and posttranslational modification involving the attachment of glycans to polypeptides. These glycans play vital roles in protein folding, stability, activity, and transport (Varki, 2017). Glycosylation is one of the most abundant protein modifications, with evidence indicating that over 50% of human proteins are glycosylated (Roth et al., 2012; Wong, 2005). Despite this, we lack a global understanding of the complex pathologies involving protein glycosylation.

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a group of inherited metabolic disorders arising from defects in the protein glycosylation pathway, including N-linked glycosylation, O-linked glycosylation, and lipid/glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis (Chang et al., 2018). N-linked CDG are further categorized into two groups based on the affected process: synthesis and transfer of glycans (Type 1) or processing of protein-bound glycans (Type 2) (Aebi et al., 1999). Mutations in the human phosphomannomutase 2 gene (PMM2) cause Type 1 CDG and are the most common cause of CDG (Ferreira et al., 2018). PMM2 forms a homodimer and catalyzes the interconversion of mannose-6-phosphate and mannose-1-phosphate (M1P) (EC 5.4.2.8). M1P is then converted to GDP-mannose, a required substrate for N-linked glycosylation glycosyltransferases.

Two of the most common pathogenic PMM2 variants found in humans are p.Val231Met and p.Phe119Leu. The V231M protein is less stable and exhibits defects in protein folding (Citro et al., 2018; Silvaggi et al., 2006), whereas the F119L protein is stable but exhibits dimerization defects (Andreotti et al., 2015; Kjaergaard et al., 1999; Pirard et al., 1999). The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains a homologous phosphomannomutase enzyme encoded by the gene SEC53. SEC53 is essential in yeast and expression of human PMM2 rescues lethality (Hansen et al., 1997; Lao et al., 2019). Previously, Lao et al., 2019 constructed strains harboring the yeast-equivalent mutations of the most common human-disease-associated PMM2 alleles including V231M (sec53-V238M) and F119L (sec53-F126L).

Using experimental evolution, we sought to identify compensatory mutations able to overcome glycosylation deficiency. Previous studies have used experimental evolution of compromised organisms, to study evolutionary outcomes and identify compensatory mutations (Harcombe et al., 2009; Helsen et al., 2020; Laan et al., 2015; Michel et al., 2017; Moser et al., 2017; Szamecz et al., 2014). Experimental evolution allows for a more robust approach than traditional suppressor screens, enabling the identification of weak suppressors and compensatory interactions between multiple mutations (Cooper, 2018; LaBar et al., 2020).

Here, we present a 1000-generation evolution experiment of yeast models of PMM2-CDG. We evolved 96 populations of yeast with wild-type SEC53, 192 populations with the sec53-V238M allele, and 96 populations with the sec53-F126L allele for 1000 generations. We sequenced 188 evolved clones to identify mutations that arose specifically in the populations harboring the sec53 human-disease-associated alleles. We find an overrepresentation of mutations in genes whose human homologs are other Type 1 CDG genes, including PGM1 (the minor isoform of phosphoglucomutase), the most commonly mutated gene in our experiment. We show that evolved mutations in PGM1 restore protein N-linked glycosylation and alleviate the slow-growth phenotype caused by the sec53-V238M disease-associated allele. We performed genetic and biochemical characterization of the pgm1 mutations and show that these mutations are dominant and allele-specific SEC53 genetic interactors.

Results

Experimental evolution improves growth of yeast models of PMM2-CDG

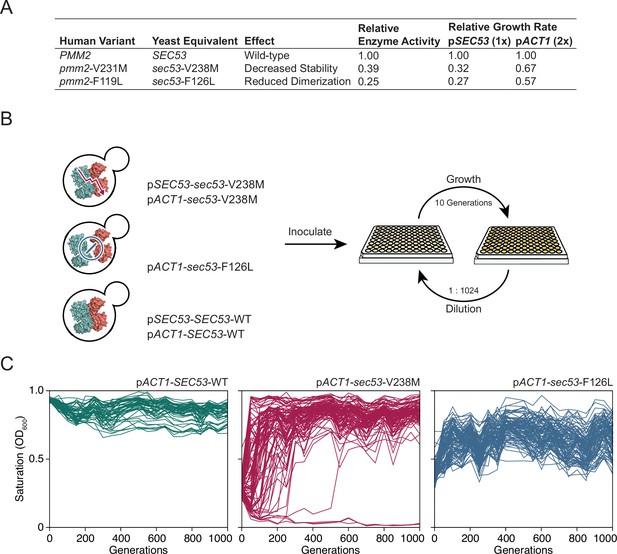

Mutations in the phosphomannomutase 2 gene, PMM2, are the most common cause of CDG. Lao et al., 2019 constructed yeast models of PMM2-CDG by making the yeast-equivalent mutations for five human-disease-associated alleles in SEC53, the yeast ortholog of PMM2. These strains have growth rate defects that correlate with enzymatic activity and promoter strength. Increasing expression levels of the mutant sec53 alleles twofold, by replacing the endogenous promoter (pSEC53) with the ACT1 promoter (pACT1), modestly improves the growth rate of sec53 disease-associated alleles (Figure 1A).

Experimental evolution of yeast models of congenital disorders of glycosylation.

(A) Table of the various sec53 alleles used in this study. In vitro enzymatic activities of Pmm2 are relative to wild-type Pmm2 and were previously reported (Pirard et al., 1999). Relative growth rates of yeast carrying various SEC53 alleles were previously reported (Lao et al., 2019). (B) Diagram of the evolution experiment. Yeast carrying sec53 mutations implicated in human disease were used to initiate replicate populations in 96-well plates: 96 populations of each mutant genotype and 48 populations of each wild-type genotype. Populations were propagated in rich glucose media, unshaken, for 1000 generations. (C) Single time-point OD600 readings of populations were taken every 50 generations during the evolution experiment as a measure of growth rate. Each line represents one population.

We chose to focus on sec53-V238M and sec53-F126L because they are two of the most common disease alleles in humans and because the mutations have distinct and well-characterized effects on protein structure and function (Figure 1A; Andreotti et al., 2015; Briso-Montiano et al., 2022; Citro et al., 2018; Kjaergaard et al., 1999; Pirard et al., 1999; Silvaggi et al., 2006). We evolved 96 haploid populations of each mutant sec53 genotype (pSEC53-sec53-V238M, pACT1-sec53-V238M, and pACT1-sec53-F126L) and 48 haploid populations of each wild-type SEC53 genotype (pSEC53-SEC53-WT and pACT1-SEC53-WT) for 1000 generations in rich glucose medium (Figure 1B). Strains with the pSEC53-sec53-F126L allele grew too slowly to keep up with a 1:210 dilution every 24 hr. Every 50 generations we measured culture density (single time-point OD600) for each population as a proxy for growth rate (Figure 1C; Figure 1—figure supplement 1).

Populations with the pACT1-sec53-V238M allele show a range of dynamics, with some populations reaching maximum saturation (OD600 ≈ 1.0) early in the experiment, while some do not even by Generation 1000 (Figure 1C). Three pACT1-sec53-V238M populations went extinct before Generation 200. While saturation levels of pACT1-sec53-F126L populations also increased over the course of the evolution experiment, none reached an OD600 close to 1.0, indicating that these populations are likely less-fit than the evolved pACT1-sec53-V238M populations. Each pSEC53-sec53-V238M population started the evolution experiment with growth rates comparable to SEC53-WT populations, indicating compensatory mutation(s) likely arose in the starting inocula (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). We therefore exclude these populations from subsequent analyses. Together, our data show that the PMM2-CDG yeast models acquired compensatory mutations throughout the evolution experiment and that the extent of compensation depends on the specific disease-associated allele.

Putative compensatory mutations are enriched for other Type 1 CDG-associated homologs

To identify the compensatory mutations in our evolved populations, we sequenced single clones from 188 populations isolated at Generation 1000 to an average sequencing depth of ~50×. These included 91 pACT1-sec53-V238M clones, 36 pACT1-sec53-F126L clones, 32 pSEC53-SEC53-WT clones, 11 pACT1-SEC53-WT clones, and 18 of the initially suppressed pSEC53-sec53-V238M clones (Supplementary file 1). Autodiploids are a common occurrence in our experimental system (Fisher et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2021). We attempted to avoid sequencing autodiploids by screening our evolved populations for sensitivity to benomyl, an antifungal agent that inhibits growth of S. cerevisiae diploids more severely than haploids (Venkataram et al., 2016).

We find that the average number of de novo mutations (single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] and small indels) varied between SEC53 genotypes, with the pACT1-sec53-F126L clones accruing more mutations per clone (8.14 ± 1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI]) compared to pACT1-sec53-V238M (5.76 ± 0.54) and SEC53-WT clones (combined pSEC53-SEC53-WT and pACT1-SEC53-WT) (6.49 ± 0.90) (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Despite screening for benomyl sensitivity, most of the sequenced clones (131/188) appear to be autodiploids, with evidence of multiple heterozygous loci. In addition, we detect several copy number variants (CNVs) and aneuploidies shared between independent populations (Figure 2—source data 1, Figure 2—source data 2).

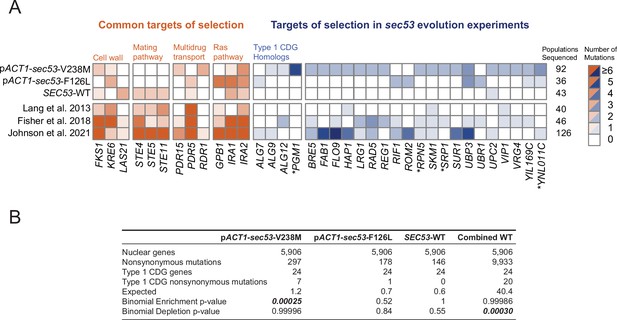

We identified putative adaptive targets of selection as genes with more mutations than expected by chance across replicate clones. Some of these common targets of selection are not specific to sec53. For example, mutations in negative regulators of Ras (IRA1 and IRA2) are found in clones from each experimental group and are also observed in other laboratory evolution experiments across a wide range of conditions (Figure 2A; Fisher et al., 2018; Gresham and Hong, 2014; Johnson et al., 2021; Kvitek and Sherlock, 2013; Lang et al., 2013; Venkataram et al., 2016).

Mutations in Type 1 congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) homologs are enriched in sec53-V238M populations.

(A) Heatmap showing the number of nonsynonymous mutations per gene that arose in the evolution experiment. Genes with two or more unique nonsynonymous mutations (and each Type 1 CDG homolog with at least one mutation) are shown. pSEC53-SEC53-WT and pACT1-SEC53-WT are grouped as ‘SEC53-WT’. For comparison, we show data from previously reported evolution experiments where the experimental conditions were identical to the conditions used here, aside from strain background and experiment duration (bottom three rows). Commonly mutated pathways are grouped for clarity. Asterisks (*) indicate previously known SEC53 genetic interactors (Costanzo et al., 2016; Kuzmin et al., 2018). (B) Binomial test for enrichment or depletion of mutations in Type 1 CDG homologs based on the number of nonsynonymous mutations observed in each experiment, the total number of yeast genes (5906), and the number of genes that are Type 1 CDG homologs (24). ‘Combined WT’ includes the SEC53-WT populations as well as three additional datasets: Lang et al., 2013, Fisher et al., 2018, and Johnson et al., 2021.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Table of recurrent copy number variants (CNVs) and aneuploidies in the evolution experiment.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig2-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Coverage plots of evolved clones.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig2-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 3

Table of mutations in Type 1 congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) homologs.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig2-data3-v2.zip

We identified putative sec53-compensatory targets as genes mutated exclusively in pACT1-sec53-V238M and/or pACT1-sec53-F126L populations (Figure 2A). The most frequently mutated genes among pACT1-sec53-F126L clones are common targets in other evolution experiments such as IRA1, IRA2, and KRE6, suggesting that mutations capable of compensating for Sec53-F126L dimerization defects are rare or not easily accessible. In contrast, while recurrently mutated genes in pACT1-sec53-V238M populations include common targets, we also identified a number of unique targets of selection, most notably in homologs of other Type 1 CDG-associated genes. We find an enrichment of mutations in CDG homologs in pACT1-sec53-V238M clones (Figure 2B; Figure 2—source data 3).

Across all sequenced populations we identified ~620 nonsynonymous mutations. As there are nearly 6000 yeast genes, the probability of any given gene receiving even a single nonsynonymous mutation is low. We are therefore well powered to detect enrichment of mutations, but underpowered to detect depletion of mutations. To gain statistical power we aggregated our SEC53-WT data with three other large datasets using similar strains and propagation regimes (Fisher et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2021; Lang et al., 2013). In this aggregate dataset, we observe a statistically significant depletion of mutations in Type 1 CDG homologs, suggesting that they are typically under purifying selection in experimental evolution (Figure 2B).

One of the CDG homologs, PGM1, is the most frequently mutated gene among pACT1-sec53-V238M clones. PGM1 encodes the minor isoform of phosphoglucomutase in yeast (Bevan and Douglas, 1969). We only find PGM1 mutations in pACT1-sec53-V238M populations which suggests their compensatory effects are unique to the sec53-V238M mutation and not glycosylation deficiency in general. Each of the five mutations in PGM1 are missense mutations, rather than frameshift or nonsense. This is consistent with selection acting on alteration-of-function rather than loss-of-function (LOF; posterior probability of non-LOF = 0.96, see Methods).

To identify the compensatory mutation(s) that arose prior to the start of the evolution experiment in the initially suppressed pSEC53-sec53-V238M populations, we analyzed the 18 sequenced clones. For each clone, we find both wild-type SEC53 and sec53-V238M alleles among sequencing reads. This could result from integration or maintenance of the covering plasmid. No sequencing reads align to the URA3 locus of our reference genome, suggesting that the plasmid marker was lost, as expected following counterselection.

Compensatory mutations restore growth

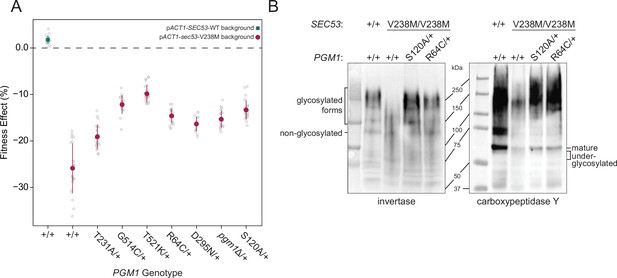

In order to validate putative compensatory mutations we reconstructed evolved mutations in PGM1 and ALG9, two genes whose human homologs are implicated in Type 1 CDG (Frank et al., 2004; Timal et al., 2012). These heterozygous evolved mutations were constructed in a homozygous pACT1-sec53-V238M diploid background (note that although each pgm1 and alg9 mutation assayed here arose in haploid-founded populations, they arose as heterozygous mutations in autodiploids). We quantified the fitness effect of each mutation using a flow cytometry-based fitness assay, competing the reconstructed strains against a fluorescently labeled, diploid version of the pACT1-SEC53-WT ancestor.

The pACT1-sec53-V238M ancestor has a fitness deficit of −25.86 ± 2.3% (95% CI) relative to wild-type. We find that each of the five evolved pgm1 mutations are compensatory in the pACT1-sec53-V238M background. The fitness effects of the sec53/pgm1 double mutants range between −19.10 ± 1.07% and −9.84 ± 0.77% (i.e., the pgm1 mutations confer a fitness benefit between 6.76% and 16.02% in the pACT1-sec53-V238M background) (Figure 3A). We also find that the evolved alg9-S230R mutation is compensatory, as the sec53/alg9 double mutant has a fitness effect of −17.89 ± 0.59% (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). We compared the fitness of these reconstructed double mutants to the fitness of the evolved clones which carry three to nine additional SNPs. In each case, the evolved clones were more fit than the reconstructed strain, except for the evolved clone containing the pgm1-D295N mutation (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Thus, while the alg9 and pgm1 mutations compensate for the sec53-V238M defect, other mutations contribute to the overall fitness of these evolved clones.

Evolved mutations rescue fitness and protein glycosylation defects of pACT1-sec53-V238M.

(A) Average fitness effects and standard deviations of reconstructed heterozygous pgm1 mutations. Fitness effects were determined by competitive fitness assays against a fluorescently labeled version of the diploid pACT1-SEC53-WT ancestor. Replicate measurements are plotted as gray circles. Pairs of pgm1 fitness effects with non-statistically significant differences: R64C-D295N, R64C-pgm1Δ, R64C-S120A, D295N-pgm1Δ, G514C-T521K, G514C-S120A, and pgm1Δ-S120A (df = 194, F = 208.1, each p > 0.05, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with Tukey post hoc test). (B) Western blots of invertase (left) and carboxypeptidase Y (right) from ancestral and reconstructed strains. In panels A and B, plus signs (+) indicate wild-type alleles. Genotypes are either homozygous wild-type (+/+), homozygous mutant (mutation/mutation), or heterozygous (mutation/+).

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Raw images of blots and Ponceau stains.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig3-data1-v2.zip

We constructed and assayed the fitness effects of the pgm1 mutations in diploid pACT1-sec53-F126L and pACT1-SEC53-WT backgrounds. Each pACT1-sec53-F126L strain was too quickly outcompeted by the reference strain to measure fitness, suggesting that the compensatory effects of the evolved pgm1 mutations are specific for the sec53-V238M mutation or any fitness improvements in the pACT1-sec53-F126L background are too minimal to detect. Each pgm1 mutation is nearly neutral in the pACT1-SEC53-WT background (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

To determine if LOF of PGM1 would phenocopy evolved mutations, we deleted one copy of PGM1 (pgm1Δ) in the diploid pACT1-sec53-V238M background and again measured fitness. We find that the heterozygous pgm1Δ mutation improves fitness (−15.28 ± 0.76%), indicating that LOF of PGM1 is compensatory in the conditions of the evolution experiment (Figure 3A). It is not immediately clear, then, why we only identify missense mutations in PGM1. Each of the mutated Pgm1 residues is located around the active site of the enzyme, based on predicted protein structure (Jumper et al., 2021; Stiers and Beamer, 2018). It could be that the evolved pgm1 mutations are LOF given this clustering but maintaining protein expression provides an ancillary benefit. To account for this possibility, we constructed a catalytically dead allele of PGM1 by mutating the enzyme’s catalytic serine (pgm1-S120A) (Stiers et al., 2017a). We find that pgm1-S120A improves pACT1-sec53-V238M fitness (−13.32 ± 0.88%) and this does not significantly differ from pgm1Δ (Figure 3A), indicating that PGM1 LOF is compensatory regardless of if that arises from loss of coding sequence or enzyme activity. We also measured fitness of homozygous pgm1 mutations (Figure 3—figure supplement 3). In all cases, the fitness effect of heterozygous and homozygous pgm1 mutants is not substantially different from each other, indicating that, by this assay, the evolved pgm1 mutations are dominant in the pACT1-sec53-V238M background, as are the pgm1Δ and pgm1-S120A mutations.

Compensatory mutations restore protein glycosylation

We have established that pgm1 mutations compensate for the growth rate defect of the sec53-V238M allele. To determine whether the evolved pgm1 mutants also compensate for the molecular defects in N-linked glycosylation we examined two representative yeast glycoproteins, invertase and carboxypeptidase Y (CPY), in our reconstructed pgm1 strains. Invertase forms both a non-glycosylated homodimer (120 kDa) and a secreted homodimer that is heavily glycosylated (approximate range of 140–270 kDa) (Gascón et al., 1968; Zeng and Biemann, 1999). Mature CPY only exists in its glycosylated form, with a molecular weight of 61 kDa (Hasilik and Tanner, 1978).

The ancestral pACT1-sec53-V238M strain shows underglycosylation of invertase and CPY. We find a reduced abundance of the higher-molecular-weight glycosylated form of invertase and mature CPY, accompanied by the appearance of underglycosylated forms of these proteins (Figure 3B). We find that evolved pgm1 mutations, pgm1Δ, and pgm1-S120A each restore glycosylation of these proteins to near-wild-type levels (Figure 3B, Figure 3—figure supplements 4 and 5). We do not observe rescue of protein glycosylation in pACT1-sec53-F126L strains carrying pgm1 mutations (Figure 3—figure supplement 6). Together, these suggest that pgm1-mediated rescue of pACT1-sec53-V238M fitness is due to restoration of protein glycosylation and the effect is specific for the pACT1-sec53-V238M background.

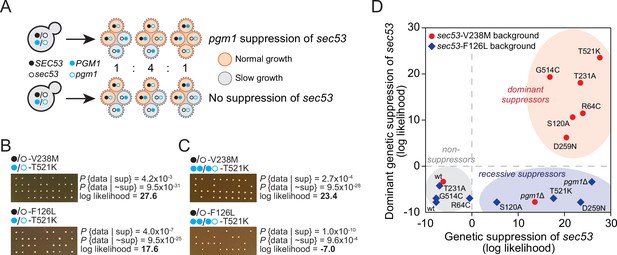

Compensatory PGM1 mutations are dominant suppressors of sec53-V238M

To further demonstrate that pgm1-mediated compensation is specific for sec53-V238M, we performed a genetic analysis by dissecting tetrads from strains that are heterozygous for both sec53 and pgm1. In the absence of a compensatory mutation, we expect 50% large colonies and all tetrads showing a 2:2 segregation of colony size due to the single segregating locus (SEC53/sec53). However, if an evolved mutation is compensatory then we expect 75% large colonies with three types of segregation patterns: 2:2, 3:1, and 4:0, large to small colonies, respectively. These three segregation patterns are expected to follow a 1:4:1 ratio assuming no genetic linkage (Figure 4A). For each genetic test, we dissected ten tetrads and performed a log-likelihood test to determine whether the segregation pattern is more consistent with genetic suppression than non-suppression (Figure 4—source data 1).

pgm1 mutations are dominant suppressors of sec53-V238M.

(A) Diagram of possible spore genotypes in the tetrad dissections. Heterozygous (e.g., SEC53/sec53 PGM1/pgm1) diploid strains could produce one of three tetrad genotypes based on allele segregation. (B) Example of pgm1-T521K dissections in a sec53-V238M background (top) and a sec53-F126L background (bottom). Listed are the probability and log likelihood of suppression, based on the ratio of normal growth (large colonies) to slow growth (no colonies or small colonies). (C) Example of PGM1::pgm1-T521K dissections in a sec53-V238M background (top) and a sec53-F126L background (bottom). (D) Plot of recessive suppression versus dominant suppression of the pgm1 mutations in the sec53-V238M background (red circles) and sec53-F126L background (blue diamonds), based on the tetrad dissections.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Log-likelihood analysis of tetrad dissections.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig4-data1-v2.zip

We find each of the evolved pgm1 mutations compensates for the V238M allele of SEC53 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). For example, dissections of a strain heterozygous for pACT1-sec53-V238M and pgm1-T521K show 78% large colonies (one 4:0 and nine 3:1, with a log-likelihood ratio of 27.6, Figure 4B). These genetic tests corroborate the results from the fitness assays by showing that all five evolved pgm1 mutations, the pgm1Δ and pgm1-S120A mutations, as well as the evolved alg9 mutation all suppress sec53-V238M (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). We next assayed each of the pgm1 mutations in a sec53-F126L background. In contrast to the fitness assays, we find several pgm1 alleles (T521K, D295N, S120A, and pgm1Δ) that suppress sec53-F126L (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). It is worth noting, however, that the degree of compensation is less than in the sec53-V238M background based on colony sizes.

To test if pgm1 mutations are dominant, we integrated a second wild-type copy of PGM1 to each of the strains such that each haploid spore will contain either two wild-type copies of PGM1 (PGM1::PGM1) or both wild-type PGM1 and mutant pgm1 (PGM1::pgm1). We find that the five evolved pgm1 mutations and pgm1-S120A, but not pgm1Δ, are dominant suppressors of sec53-V238M in the genetic assay (Figure 4C, D; Figure 4—figure supplement 2). For the sec53-F126L background, we find no dominant suppressors.

Reduction of Pgm1 activity alleviates deleterious effect of PMM2-CDG in yeast

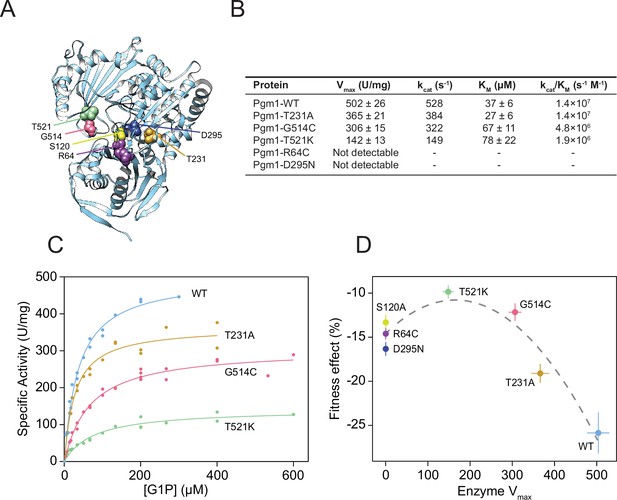

To determine how the evolved mutations alter Pgm1 enzymatic activity, we cloned mutant and wild-type PGM1 alleles into bacterial expression vectors, purified recombinant enzyme, and assayed phosphoglucomutase activity using a standard coupled enzymatic assay (Figure 5A; Figure 5—figure supplement 1). We find that mutant Pgm1 have variable activities, ranging from near-wild-type (Pgm1-T231A) to non-detectable (Pgm1-R64C and Pgm1-D295N) (Figure 5B, C). The near complete loss of activity of Pgm1-D295N is unsurprising since D295 coordinates a Mg2+ ion that plays an essential role during catalysis (Stiers et al., 2016) and we verify that all the active forms show very low activity in the presence of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Figure 5—source data 1). Thermostability did not differ between enzymes with detectable activity (Figure 5—figure supplement 2).

Complete loss of Pgm1 activity overshoots a fitness optimum.

(A) AlphaFold structure of S. cerevisiae Pgm1 (Jumper et al., 2021). Mutated residues shown as spheres. (B) Kinetic parameters of recombinant Pgm1 enzymes as determined by a coupled enzymatic assay. Values ± 95% confidence intervals. (C) Michaelis–Menten curves of wild-type and mutant Pgm1. Replicate measurements are plotted as circles. (D) Pgm1 enzyme Vmax versus the corresponding allele’s fitness effect in the diploid pACT1-sec53-V238M background (as shown in Figure 3A). Horizontal and vertical error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Best fit regression shown as a dashed curve (y = 14.583 + 0.04613x − 0.00014x2, R2 = 0.907, df = 4, F = 37.34, p = 0.0258, analysis of variance [ANOVA]). Note that we did not measure Pgm1-S120A activity and assume null activity.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Other biochemical properties of mutant Pgm1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/79346/elife-79346-fig5-data1-v2.zip

Comparison of the kinetic parameters of active mutant enzymes shows a reduction of maximal velocity (Vmax) between 27% and 72% relative to wild-type Pgm1. Based on the apparent Michaelis constant (Km), substrate affinities of Pgm1-G514C and Pgm1-T521K are lower than wild-type Pgm1 (t = 4.30 and 3.14, df = 35.78 and 20.47, p = 0.0001 and 0.0051, respectively, Welch’s modified t-test). Pgm1-T231A shows an increased affinity compared to wild-type Pgm1, but this difference is not statistically significant (t = 1.94, df = 34.68, p = 0.0601, Welch’s). Together these indicate that the five evolved pgm1 mutations have varying effects on enzymatic activity. The relationship between pgm1 fitness and Pgm1 Vmax is best fit by a quadratic, rather than a linear, function (Figure 5D). Therefore, optimal fitness is attained by tuning down, but not eliminating, Pgm1 activity.

Mutant Pgm1 does not have increased phosphomannomutase activity

Phosphoglucomutases can exhibit low levels of phosphomannomutase activity, and we reasoned that active-site mutations in Pgm1 could alter epimer specificity from glucose to mannose, directly compensating for the loss of Sec53 activity (Lowry and Passonneau, 1969). We tested this in two ways. First, we directly measured phosphomannomutase activity of wild-type Pgm1 and two mutant Pgm1, using a 31P-NMR spectroscopy-based assay (Figure 5—figure supplements 1 and 3A). We find that wild-type Pgm1 and Pgm1-G514C show comparably low phosphomannomutase activity, accounting for 3.5% and 3.0% of their phosphoglucomutase activity, respectively. We could not detect any phosphomannomutase activity for Pgm1-D295N. We also tested for phosphomannomutase activity indirectly by determining whether M1P acted as a competitive inhibitor in the phosphoglucomutase assay. If mutant Pgm1 had altered epimer specificity, we would expect M1P to compete with glucose-1-phosphate (G1P) for residency within the active site, leading to an apparent decrease in phosphoglucomutase activity. However, we find no effect of the addition of M1P on phosphoglucomutase activity for any of the Pgm1 enzymes tested (Figure 5—figure supplement 3B). Together, these results indicate that mutant Pgm1 does not have enhanced phosphomannomutase activity.

Pgm1 mutations increase intracellular glucose-1,6-bisphosphate levels

Glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G16P) is required as an activator of both Pgm1 and Pmm2 (Sec53) and can stabilize pathogenic variants of Pmm2 (Monticelli et al., 2019). The only known source of G16P in yeast is low-level dissociation during the phosphoglucomutase reaction of Pgm1 and Pgm2. We reasoned that evolved pgm1 mutations may increase intracellular levels of G16P which, in turn, would stabilize Sec53-V238M. Each active form of Pgm1 exhibits barely detectable activity in the absence of G16P and we determined an apparent half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of G16P for several Pgm1 enzymes (Figure 5—source data 1). Given that Pgm1 is the minor isoform of phosphoglucomutase in yeast, we also reasoned that it could act as a glucose-1,6-bisphosphatase, similar to human PMM1 (Veiga-da-Cunha et al., 2008). We performed a specific glucose-1,6-bisphosphatase assay on wild-type and mutant Pgm1 enzyme (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). However, none of the mutant Pgm1 enzymes have detectable glucose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity.

We next assessed G16P levels for two pgm1 mutant alleles in both the pACT1-sec53-V238M and the pACT1-SEC53-WT backgrounds (Figure 5—figure supplement 4). We find that strains heterozygous for pgm1-T521K or pgm1-D295N show statistically significant increases in the amount of G16P present compared to wild-type PGM1, in the sec53-V238M background (W = 24 and 8, p = 0.003 and 0.0002, respectively, Mann–Whitney U-test). However, this difference is not significant in the SEC53-WT background (W = 41 and 15, p = 0.35 and 0.078, respectively, Mann–Whitney).

Finally, we also reasoned that pgm1 mutations could differently affect the forward and reverse directions of the phosphoglucomutase reaction, with possible effects on the flux of metabolites within the cell. We analyzed the forward and reverse reactions of Pgm1, Pgm1-T231A, and Pgm1-G514C using G1P or glucose-6-phopshate (G6P) as the substrate (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). We again used 31P-NMR spectroscopy, as G1P and G6P have clearly distinguishable signals (Figure 5—figure supplement 5). The ratio of forward to reverse reactions is 3.0 ± 1.2 and 4.3 ± 1.1 (± standard deviation) for Pgm1-T231A and Pgm1-G514C, respectively. Although a slightly higher ratio was obtained for wild-type Pgm1 (7.4 ± 3.1), the differences between wild-type and Pgm1-T231A or Pgm1-G514C are not statistically significant (W = 1 and 2, p = 0.057 and 0.53, respectively, Mann–Whitney).

Discussion

The budding yeast S. cerevisiae is a powerful system for studying conserved aspects of eukaryotic cell biology due to its fast doubling time, small genome size, genetic tractability, and the wealth of genomics tools available (Botstein and Fink, 2011). Many human genes are functionally identical to—and can complement—their yeast homologs (Kachroo et al., 2015). ‘Humanizing’ yeast by replacing a yeast ortholog with the human gene or making an analogous human mutation in a yeast ortholog enables functional studies of human disease (Franssens et al., 2013; Laurent et al., 2016). For example, Mayfield et al. characterized the severity of 84 alleles of human CBS (cystathionine-β-synthase) that are associated with homocystinuria, identifying those alleles where cofactor supplementation can restore high levels of enzymatic function (Mayfield et al., 2012). Gammie et al. characterized 54 MSH2 variants associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer showing that about half of the variants have enzymatic function but are targeted for degradation (Gammie et al., 2007). Subsequent work showed that treatment with proteasome inhibitors restores mismatch repair and chemosensitivity in yeast harboring these disease-associated variants (Arlow et al., 2013). In additional to functional characterization, yeast models of human disease enable screens for genetic interactions, thereby uncovering new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, for example, is due to mutations in WAS, the human homolog of LAS17. Using a temperature-sensitive lethal allele of las17, Filteau et al. isolated compensatory mutations in two yeast strains. The authors identified both common and background-specific mechanisms of compensation, including LOF of CNB1 (Calcineurin B), which is phenocopied by inhibition with cyclosporin A (Filteau et al., 2015).

Here, we use experimental evolution to identify mechanisms of genetic compensation in humanized yeast models of PMM2-CDG. We evolved 96 replicate populations for 1000 generation in rich glucose medium using strains carrying wild-type SEC53 (the yeast homolog of PMM2) and two human-disease-associated alleles (sec53-V238M and sec53-F126L). We show that compensatory mutations arose throughout the evolution experiment. Fitness gains were greater for populations with the pACT1-sec53-V238M allele compared to the pACT1-sec53-F126L allele, which showed modest gains in fitness (Figure 1C). This indicates that the number of compensatory mutations and/or the ameliorative effects of compensatory mutations are greater for the pACT1-sec53-V238M allele compared to the pACT1-sec53-F126L allele. Our sequencing and reconstruction experiments show that both explanations are true. While the pACT1-sec53-V238M populations showed several unique targets of selection, the pACT1-sec53-F126L populations mostly acquired mutations in targets of selection observed in other evolution experiments (Figure 2A). In addition, the genetic reconstruction experiments show that some of the pgm1 mutations are recessive suppressors of sec53-F126L, whereas all five pgm1 mutations are dominant suppressors of sec53-V238M (Figure 4). The latter is unsurprising given that each pgm1 mutation arose as a heterozygous mutation in a sec53-V238M autodiploid background.

Twenty-four genes have been associated with Type 1 CDG in humans (Aebi et al., 1999). All but two Type 1 CDG genes have at least one functional homolog in yeast, and most map one-to-one (Figure 2—source data 3). We find an overrepresentation of mutations in Type 1 CDG homologs in the evolved pACT1-sec53-V238M populations (Figure 2B). This enrichment is striking considering that we observe a significant depletion of mutations in these same genes aggregated across evolution experiments with wild-type SEC53, which suggests that they are normally under purifying selection. Specifically, we find five mutations in PGM1, two in ALG9, and one in ALG12. In addition, one ALG7 mutation was identified in a single pACT1-sec53-F126L population. Of these four, only PGM1 is a known SEC53 genetic interactor, and none are known Sec53 physical interactors. ALG7 encodes an acetylglucosaminephosphotransferase responsible for the first step of lipid-linked oligosaccharide synthesis, downstream of SEC53 in the N-linked glycosylation pathway (Barnes et al., 1984; Kukuruzinska and Robbins, 1987). ALG9 and ALG12 act downstream of SEC53 and encode mannosyltransferases, responsible for transferring mannose residues from dolichol-phosphate-mannose to lipid-linked oligosaccharides (Burda et al., 1999; Burda et al., 1996; Cipollo and Trimble, 2002; Frank and Aebi, 2005). This oligosaccharide is eventually transferred to a polypeptide. Each of the evolved mutations in these genes is predicted to have deleterious effects on protein function based on PROVEAN scores (Supplementary file 1; Choi and Chan, 2015). This suggests that prodding steps in N-linked glycosylation alleviates the deleterious effect of sec53 disease-associated alleles, perhaps by altering pathway flux to match lowered M1P availability. Evidence from human studies supports the idea of downstream genetic modifiers affecting PMM2-CDG phenotypes. For example, there is not a direct correlation between clinical phenotypes and biochemical properties of PMM2 (Citro et al., 2018; Freeze and Westphal, 2001). One such modifier is a variant of the glucosyltransferase ALG6, which has been implicated in worsening clinical outcomes of PMM2-CDG individuals (Bortot et al., 2013; Westphal et al., 2002).

In addition to Type 1 CDG homologs, we identify several other classes of putative genetic suppressors. Both the sec53-V238M and sec53-F126L mutations retain partial functionality and Lao et al., 2019 showed that increasing expression of these alleles improves growth. We, therefore, expected to find CNVs and aneuploidies as compensatory mutations. Though we do identify several strains that show evidence of CNVs at the HO locus on Chromosome IV, where the sec53 alleles reside in our strains, karyotype changes are not a major route of adaptation (Figure 2—source data 1). Reduced function of mutant Sec53 could be due to destabilization and degradation of the protein. We identify recurrent mutations in the 26S proteasome lid subunit RPN5 in the pACT1-sec53-V238M background, in the E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR1 in the pACT1-sec53-F126L background, and in the ubiquitin-specific protease UBP3 in both pACT1-sec53 backgrounds (Figure 2). In addition, we identify a mutation in the ubiquitin-specific protease UBP15 in a single pACT1-sec53-V238M clone. And finally, we observe multiple independent mutations in the known SEC53-interactors RPN5, SRP1, and YNL011C in sec53 populations, which could have positive genetic interactions with sec53 (Figure 2).

We find a high probability that the mutational spectrum of PGM1 (five missense mutations, 0 frameshift/nonsense) resembles selection for non-LOF (posterior probability = 0.96). However, PGM1 LOF (pgm1Δ) provides a fitness benefit indistinguishable from two evolved mutations (pgm1-R64C and pgm1-D295N) and higher than one evolved mutation (pgm1-T231A). Likewise, the pgm1Δ allele restores invertase and CPY glycosylation and growth in the tetrad analyses, albeit recessively. It is not immediately clear, therefore, why we do not observe frameshift/nonsense mutations in PGM1 in the evolution experiment. We have previously shown that genetic interactions between evolved mutations are not always recapitulated by gene deletion (Vignogna et al., 2021). Given that most of the evolved clones containing pgm1 mutations are more fit than the reconstructed strains, it is possible that other evolved mutations interact epistatically only with non-LOF pgm1 mutations. However, there are no shared mutational targets (genes or pathways) among the evolved clones with pgm1 mutations and only one evolved pgm1 clone contains a mutation in a known PGM1 interactor (FRA1). These suggest any putative genetic interactions with our evolved pgm1 mutations are allele specific.

Using tetrad dissections, we show that each evolved pgm1 mutation and the catalytically dead pgm1-S120A mutation are dominant suppressors of sec53-V238M. pgm1Δ is not a dominant suppressor based on the tetrad analyses, contrary to the fitness assays where the heterozygous pgm1Δ allele confers a fitness benefit comparable to several evolved mutations. This discrepancy likely results from differences in ploidy or growth medium of the two experiments—diploids in liquid culture versus haploids on agar plates. We also find that several pgm1 mutations (T521K, D295N, pgm1Δ, and S120A) are recessive suppressors of the sec53-F126L allele in the tetrad dissections, whereas we were unable to detect any improvement using fitness assays. Three of these four mutations have no detectable enzymatic activity. However, the R64C allele, which also does not have detectable enzymatic activity does not suppress.

To test specific hypotheses for the mechanism of suppression of sec53 disease alleles by mutation of pgm1, we characterized the biochemical properties of purified recombinant Pgm1 mutant proteins. We find that phosphoglucomutase activity ranges from non-detectable activity (R64C and D295N) to near wild-type (T231). Based on well-characterized human and rabbit PGM1 structures, R64C and D295N mutations likely affect active-site integrity (Liu et al., 1997; Stiers et al., 2016). R64 helps hold the catalytic serine (S120) in place and D295 coordinates a catalytically essential Mg2+ ion. The T231A mutation, which occurs in a residue near the metal-binding loop, shows the highest activity levels among our mutant Pgm1 enzymes. The other two mutations with low but detectable activity, G514C and T521K, both occur in the phosphate-binding domain of Pgm1, a region important for substrate binding (Beamer, 2015; Stiers et al., 2017a; Stiers et al., 2017b; Stiers and Beamer, 2018). Comparing pgm1 fitness effects versus their corresponding enzyme Vmax we find an inverted U-shaped curve, where reducing phosphoglucomutase activity improves fitness, but complete loss of activity overshoots the optimum (Figure 5D). Plotting fitness versus kcat/Km results in a qualitatively similar trend, although comparing kcat/Km between mutant enzymes may not be appropriate (Eisenthal et al., 2007).

We tested several hypotheses involving Pgm1 alteration-of-function. First, the evolved Pgm1 proteins could directly complement the loss of Sec53 phosphomannomutase activity by switching epimer specificity from glucose to mannose. However, we do not observe increased phosphomannomutase activity in the Pgm1 mutant proteins, nor is this hypothesis consistent with our genetic data: direct complementation would be expected to suppress both the sec53-V238M and sec53-F126L alleles.

A second possible mechanism of suppression is increasing the production of G16P. G16P is an endogenous activator and stabilizer of Pmm2 (Sec53). Compounds that raise G16P levels by increasing its production and/or slowing its degradation show promise as candidates for treatment of PMM2-CDG (Iyer et al., 2019; Monticelli et al., 2019). Whereas higher eukaryotes and some bacteria have a dedicated G16P synthase, in yeast G16P is produced as a dissociated intermediate of the phosphoglucomutase reaction (Maliekal et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2021). We hypothesized that evolved mutations in PGM1 may increase the rate of G16P dissociation. Recent work has shown that a mutation affecting Mg2+ coordination in L. lactis β-phosphoglucomutase can increase dissociation of β-G16P in vitro (Wood et al., 2021). While we did not directly measure G16P synthase activity of Pgm1, we find that intracellular levels of G16P are increased in strains with pgm1-T521K or pgm1-D295N. We cannot, however, determine if the observed increase in G16P is sufficient to rescue glycosylation. There may be other metabolic changes caused by the pgm1 mutations that impact Sec53 activity and glycosylation.

A third possible mechanism of compensation is the indirect increase of G16P by increasing the relative flux of the reverse (G6P to G1P) reaction relative to the forward (G1P to G6P) reaction. This would create a futile cycle of G1P/G6P interconversion, which is expected to result in higher intracellular G16P. This hypothesis is attractive in that it accounts for three observations regarding the evolved pgm1 mutations: (1) the observation of only missense (not nonsense or frameshift) mutations in the evolution experiment, (2) the dominance of suppressors in our genetic assay, and (3) greater extent of suppression for the stability mutant (V238M) of SEC53. Nevertheless, the observation that complete loss of Pgm1 enzymatic activity improves growth of sec53 mutants suggests that there are multiple mechanisms of suppression through PGM1.

There is truth to the saying that ‘a selection is worth a thousand screens’. Experimental evolution takes what would otherwise be a screen—looking for larger colonies on a field of smaller ones—and turns it into a selection. Here, we demonstrate the power of yeast experimental evolution to identify genetic mechanisms that compensate for the molecular defects of PMM2-CDG disease-associated alleles. This general approach is applicable to other human disease alleles that affect core and conserved biological processes including protein glycosylation, ribosome maturation, mitochondrial function, and RNA modification. Mutations that impinge upon these processes are often highly pleiotropic. In humans, salient phenotypes may be neurological or developmental, but in yeast, these disease alleles invariably lead to slow growth. With a population size of 105, evolution can act on differences as small as 0.001%, far below the ability to resolve on plates. Even our best fluorescence-based assays can only resolve differences of ~0.1% (Lang and Botstein, 2011). With a genome size of 107 bp, a mutation rate of 10−10 per bp per generation, and with continuous selective pressure exerted over thousands of generations, each population will sample hundreds of thousands of coding-sequence mutations. Over longer time scales, experimental evolution can be used to identify rare suppressor mutations, suppressor mutations with modest fitness effects, and/or complex compensatory interactions involving multiple mutations, which are largely absent from current genetic interaction networks.

Methods

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pTC416-SEC53 | Lao et al., 2019 | Wild-type SEC53 plasmid (CEN-ARS) | Plasmid map: https://bit.ly/3nBYllD |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pML104-NatMx3 | Addgene (83477) | Cas9 plasmid | Modified plasmids available upon request |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pAG25 | Addgene (35121) | Integrating plasmid | Modified plasmids available upon request |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pGEX-2T | Cytiva Life Sciences (28954653) | Bacterial expression plasmid | Modified plasmids available upon request |

| Antibody | anti-carboxypeptidase rabbit polyclonal antibody | Abcam (ab181691) | (1:1000) | |

| Antibody | anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technologies (5127) | (1:2000) | |

| Antibody | anti-invertase goat polyclonal antibody | Novus Biologicals (NB120-20597) | (1:1000) | |

| Antibody | anti-goat IgG HRP-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody | Rockland Immunochemicals (18-8814-33) | (1:2000) |

Experimental evolution

The haploid strains used in the evolution experiment are S288c derivatives and were described previously (Lao et al., 2019). Each strain maintains a URA3-marked plasmid encoding wild-type SEC53 (pTC416-SEC53 described in Lao et al., 2019). Strains with the pSEC53-sec53-F126L allele grew too slowly to keep up with a 1:210 dilution every 24 hr.

To initiate the evolution experiment, strains were struck to synthetic defined media (complete supplement mixture [CSM] minus arginine, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% dextrose) containing 5-Fluoroorotic Acid (5FOA) (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) to isolate cells that spontaneously lost pTC416-SEC53. A single colony was chosen for each strain and used to inoculate 10 ml of YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) plus ampicillin and tetracycline. These cultures grew to saturation then were distributed into 96-well plates. Every 24-hr populations were diluted 1:210 using a BiomekFX liquid handler into 125 μl of YPD plus 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml tetracycline to prevent bacterial contamination. Plates were then left at 30°C without shaking. The dilution scheme equates to 10 generations of growth per day at an effective population size of ~105. Every 100 generations, 50 μl of 60% glycerol was added to each population and archived at −80°C.

OD600 was measured every 50 generations over the course of the evolution experiment. After daily dilutions were completed, populations were resuspended by orbital vortexing at 1050 rpm for 15 s then transferred to a Tecan Infinite M200 Pro plate reader for sampling.

Whole-genome sequencing

Benomyl assays were performed by spotting 5 μl of populations onto YPD plus 20 μg/ml benomyl (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) and incubating at 25°C. Ploidy was then inferred by visually comparing growth of evolved populations to control haploid and diploid strains.

Single clones were isolated for sequencing by streaking 5 μl of cryo-archived populations to YPD agar. One clone from each population was randomly chosen and grown to saturation in 5 ml YPD, pelleted, and frozen at −20°C. Genomic DNA was harvested from frozen cell pellets using phenol–chloroform extraction and precipitated in ethanol. Total genomic DNA was used in a Nextera library preparation as described previously (Buskirk et al., 2017). Pooled clones were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer by the Sequencing Core Facility at the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University.

Sequencing analysis

Raw sequencing data were concatenated and then demultiplexed using a dual-index barcode splitter (https://bitbucket.org/princeton_genomics/barcode_splitter/src/master/). Adapter sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014). Modified S288c reference genomes were constructed using reform (https://github.com/gencorefacility/reform; Khalfan, 2021) to correct for strain-construction-related differences between our strains and canonical S288c. Trimmed reads were aligned to these modified S288c reference genomes using BWA and mutations were called using FreeBayes (Garrison and Marth, 2012; Li and Durbin, 2009). VCF files were annotated with SnpEff (Cingolani et al., 2012). All calls were confirmed manually by viewing BAM files in IGV (Thorvaldsdóttir et al., 2013). Clones were predicted to be diploids if two or more mutations were called at an allele frequency of 0.5. CNVs and aneuploidies were called via changes in sequencing coverage using Control-FREEC (Boeva et al., 2012). CNVs and aneuploidies were confirmed by visually inspecting coverage plots.

Yeast strain construction

Evolved mutations were reconstructed via CRISPR/Cas9 allele swaps. For mutations that fall within a Cas9 gRNA site (alg9-S230R, pgm1-T231A, and pgm1-G514C), repair templates were produced by PCR-amplifying 500–2000 bp fragments centered around the mutation of interest from evolved clones. Commercially synthesized dsDNA fragments (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) were used as repair templates for all other mutations (pgm1-R64C, pgm1-S120A, pgm1-D295N, pgm1-T521K, and pgm1Δ). These 500 bp fragments contained our mutation of interest as well as one to two synonymous mutations in the Cas9 gRNA site to halt cutting. The pgm1Δ repair template was a dsDNA fragment consisting of 250 bp upstream then 250 bp downstream of the ORF. Repair templates were cotransformed into haploid ancestral strains with a plasmid encoding Cas9 and gRNAs targeting near the mutation site (Addgene #83476) (Laughery et al., 2015).

Heterozygous mutant strains were constructed by mating haploid mutants to MATα versions of their respective ancestral strains. Homozygous mutant strains were constructed by reconstructing mutations in MATα versions of the ancestral strains and mating them to the respective MATa mutant strain. Successful genetic reconstructions were confirmed via Sanger sequencing (Psomagen, Rockville, MD, USA).

Linked PGM1 strains used for tetrad dissections were constructed by transforming strains with a linearized integrating plasmid (Addgene #35121) containing wild-type PGM1 (Goldstein and McCusker, 1999). Successful integration of the plasmid next to the endogenous PGM1 locus was confirmed via PCR. Strain information in Supplementary file 2.

Competitive fitness assays

We measured the fitness effect of evolved mutations using competitive fitness assays described previously with some modifications (Buskirk et al., 2017). Query strains were mixed 1:1 with a fluorescently labeled version of the pACT1-SEC53-WT ancestral diploid strain. Each pACT1-sec53-F126L strain was outcompeted immediately by the reference at this ratio, so we also tried mixing at a ratio of 50:1. Cocultures were propagated in 96-well plates in the same conditions in which they evolved for up to 50 generations. Saturated cultures were sampled for flow cytometry every 10 generations. Each genotype assayed was done so with at least 24 technical replicates (competitions) of 4 biological replicates (2 clones isolated each from 2 isogenic but separately constructed strains). Analyses were performed in Flowjo and R.

LOF/non-LOF Bayesian analysis

From reconstruction data from previously published evolution experiments (Fisher et al., 2018; Lang et al., 2013; Marad et al., 2018), we identified ten genes where selection is acting on LOF (ACE2, CTS1, ROT2, YUR1, STE11, STE12, STE4haploids, STE5, IRA1, and IRA2) and six genes where selection is for non-LOF (CNE1, GAS1, KEG1, KRE5, KRE6, and STE4autodiploids). These data established prior probabilities that selection is acting on LOF (0.625) or non-LOF (0.375). We then determined the conditional probabilities of missense and frameshift/nonsense mutations given selection for LOF and non-LOF using 240 mutations across these 16 genes as well as 414 5FOA-resistant mutations at URA3 and 454 canavanine-resistant mutations at CAN1 (Lang and Murray, 2008). From these data, we can estimate the log likelihood and posterior probabilities that selection is acting on LOF or non-LOF given the observed mutational spectrum for any given gene (Supplementary file 3).

CPY and invertase blots

Strains were grown in 5 ml YPD plus 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml tetracycline until saturated, then pelleted, and frozen at −20°C. Cell pellets were lysed in Ripa lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 25 mM Tris [pH 7.4]) with protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), incubated for 30 min on ice, sonicated five times briefly, incubated for a further 10 min on ice, and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was quantified by Micro BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher). 30 μg of each lysate were prepared in Lamelli buffer and were incubated at 95°C for 5 min and chilled at 4°C. Lysates were separated on a 6% or 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) gel. Protein was transferred to 0.2 µm pore nitrocellulose at 100 V for 100 min at 4°C in Towbin buffer. The membrane was rinsed and stained with Ponceau S for normalization. The membranes were blocked with 5% milk/TBST for 1 hr at room temperature.

CPY blots were incubated with an anti-carboxypeptidase antibody at 1:1000 overnight at 4°C and washed three times with TBST. The blots were then incubated with anti-rabbit IgG HRP diluted 1:2000 in milk/TBST for 1 hr, washed three times and developed with ECL reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Invertase blots were prepared similarly with an anti-invertase antibody and anti-goat IgG HRP. All images were captured on the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Analysis was done with Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad). Raw images of blots and Ponceau stain controls are available in Figure 3—source data 1.

Tetrad dissection and inference of genetic interactions

Heterozygous yeast strains (i.e., SEC53/sec53 PGM1/pgm1) were sporulated by resuspending 1 ml of overnight YPD culture in 2 ml of SPO++ (1.5% potassium acetate, 0.25% yeast extract, 0.25% dextrose, 0.002% histidine, 0.002% tryptophan) and incubated on a roller-drum for ~7 days at room temperature. Ten tetrads per strain were dissected on YPD agar and then incubated for 48 hr at 30°C. We performed a log-likelihood test to determine if patterns of segregation are indicative of suppression (Figure 4—source data 1). Note that in order to calculate conditional probabilities we had to include an error term (0.01) to account for biological noise in the real data. Our inference of suppression, however, is robust to our choice of error value.

Bacterial growth and lysis

Wild-type and mutant PGM1 alleles were cloned into the expression vector pGEX-2T. Cloned vectors were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Bacteria were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium plus 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin. Each PGM1 allele was expressed by induction at 0.1 OD with 0.1 mg/ml IPTG for 16 hr at 15°C. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stored at −80°C. Bacterial lysis was accomplished in 25 mM Tris buffer (pH 8) containing 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), by adding 1 mg/ml lysozyme and 2.5 µg/ml DNase. Clear extract was then obtained by centrifugation.

Protein purification

Protein purification was accomplished using Glutathione Sepharose High Performance resin (GSTrap by Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) and Benzamidine Sepharose 4 Fast Flow resin (HiTrap Benzamidine FF by Cytiva). Cleavage of the GST-tag was conducted on-column by adding thrombin. All the procedures were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, clear extract obtained from 50 ml of bacterial culture was loaded onto the GSTrap column (5 ml), previously equilibrated with 25 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 2 mM DTT and 5% glycerol. Unbound protein was eluted, then the column was washed with 20 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 1 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5% glycerol (buffer A). Thrombin (30 units in 5 ml of buffer A) was loaded and the column was incubated for 14–16 hr at 10°C. GSTrap and HiTrap Benzamidine columns were connected in series, and elution of the untagged protein was accomplished with buffer A. Fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and activity assays. Active fractions were finally collected and concentrated by ultrafiltration. A yield spanning 1.0–4.6 mg of protein per liter of bacterial culture was obtained.

Each protein was obtained in a pure, monomeric form as judged by SDS–PAGE and gel filtration analyses, with a single band observed at the expected molecular weight (63 kDa). Gel filtration analysis was performed on BioSep-SEC-S 3000 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 1 ml/min. The eluent was 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 1 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl.

Activity assays

Phosphoglucomutase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm and 29°C by following the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH in a 0.3 ml reaction mixture containing 25 mM Tris (pH 8), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.25 mM NADP+, and 2.7 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in the presence of 0.3 mM G1P and 0.02 mM G16P. Additional experiments were performed with the addition of M1P (10, 50, and 200 μM). Km were evaluated by measuring activity in the presence of G1P ranging from 0 mM to 0.6 mM. Analyses were performed in R using the drc package (Ritz et al., 2015). Bisphosphatase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 340 nm and 29°C in the presence of 0.1 mM G16P, 0.25 mM NADP+, and 2.7 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Activity expressed as the number of micromoles of substrate transformed per minute per mg of protein under the standard conditions.

Thermostabilities of Pgm1 were determined by incubating purified protein for 5 or 10 min at different temperatures (30, 35, 40, and 45°C) in 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 1 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA. After cooling on ice, residual activity was measured under standard conditions.

31P-NMR spectroscopy

Phosphoglucomutase and phosphomannomutase activity were measured by 31P-NMR spectroscopy (Citro et al., 2017). This assay allows us to exclude the effects on the change in absorbance due to impurities that could be substrates for the ancillary enzymes required for the assay. This is of utmost importance when the activity is particularly low and measuring the rate of change in absorbance requires long incubation times, as it is the case of phosphomannomutase activity for Pgm1. A discontinuous assay was performed. Appropriate amounts of proteins were incubated at 30°C with 1 mM G1P or M1P in 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, in the presence of 20 μM G16P for up to 60 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 mM EDTA on ice and heat inactivation. The content of the residual substrate (M1P or G1P) and/or the product (M6P or G6P) were measured recording 31P-NMR spectra. Creatine phosphate was added as an internal standard for the quantitative analysis. The 1H-decoupled, one-dimensional 31P spectra were recorded at 161.976 MHz on a Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer 400 MHz, equipped with a BBO BB-H&F-D CryoProbe Prodigy fitted with a gradient along the z-axis, at a probe temperature of 27°C. Spectral width 120 ppm, delay time 1.2 s, and pulse width of 12.0 μs were applied. All the samples contained 10% 2H2O for internal lock.

Similarly, forward (G1P to G6P) and reverse (G6P to G1P) phosphoglucomutase activities were measured following the same procedure described above, with 1 mM G1P or G6P as the substrate.

Quantification of G16P abundance

Yeast metabolite extraction was performed as described previously (Gonzalez et al., 1997). Briefly, five replicate cultures per genotype were grown in 5 ml YPD plus 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml tetracycline at 30°C. 107 cells of mid-log culture were collected on nylon filters, washed with 10 ml cold PBS, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized. Cells were then treated with an ice-cold solution containing 14% HClO4 and 91 mM imidazole, frozen and thawed five times (dry ice/acetone followed by 40°C bath) with vigorous shaking between each cycle, then centrifuged at 13,500 × g at 4°C. Supernatant was neutralized with 3 M K2CO3 and centrifuged again at 13,500 × g at 4°C to eliminate salt precipitate.

G16P in the metabolite extracts was measured through stimulation of rabbit muscle phosphoglucomutase as described previously (Veiga-da-Cunha et al., 2008). Phosphoglucomutase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm, in a mixture containing 87 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 5.6 mM MgCl2, 0.11 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 0.048 mM NADP+, 0.48 mM G1P, 0.26 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, at 36°C. G1P had previously been purified from G16P through anionic exchange chromatography on AG1x8 Hydroxide Form column in step gradient of triethylammonium bicarbonate from 0.01 M to 1 M (Monticelli et al., 2019). Three technical replicates for each of the five biological replicates were assayed. 0.0–0.15 µM commercial G16P (Merck & Co, Rahway, NJ, USA) was used as the standard.

Data availability

The short-read sequencing data reported in this study have been deposited to the NCBI BioProject database, accession number PRJNA784975.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA784975. Experimentally-evolved Saccharomyces cerevisiae clones.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA205542. The sequencing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA422100. Evolved Autodiploid Clones.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA668346. Evolved S. cerevisiae population sequencing.

References

-

Asparagine-Linked glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: genetic analysis of an early stepMolecular and Cellular Biology 4:2381–2388.https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.4.11.2381-2388.1984

-

Mutations in hereditary phosphoglucomutase 1 deficiency map to key regions of enzyme structure and functionJournal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 38:243–256.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-014-9757-9

-

Genetic control of phosphoglucomutase variants in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeJournal of Bacteriology 98:532–535.https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.98.2.532-535.1969

-

Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence dataBioinformatics 30:2114–2120.https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

-

Insight on molecular pathogenesis and pharmacochaperoning potential in phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency, provided by novel human phosphomannomutase 2 structuresJournal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 45:318–333.https://doi.org/10.1002/jimd.12461

-

Congenital disorders of glycosylationAnnals of Translational Medicine 6:477.https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.10.45

-

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae alg12delta mutant reveals a role for the middle-arm alpha1,2man- and upper-arm alpha1,2manalpha1,6man- residues of glc3man9glcnac2-PP-dol in regulating glycoprotein glycan processing in the endoplasmic reticulum and golgi apparatusGlycobiology 12:749–762.https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwf082

-

Catalytic efficiency and kcat/Km: a useful comparator?Trends in Biotechnology 25:247–249.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.03.010

-

Recognizable phenotypes in CDGJournal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 41:541–553.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-018-0156-5

-

Identification and functional analysis of a defect in the human ALG9 gene: definition of congenital disorder of glycosylation type ILAmerican Journal of Human Genetics 75:146–150.https://doi.org/10.1086/422367

-

The benefits of humanized yeast models to study Parkinson’s diseaseOxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2013:760629.https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/760629

-

Comparative study of the properties of the purified internal and external invertases from yeastThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 243:1573–1577.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)93580-5

-

The functional basis of adaptive evolution in chemostatsFEMS Microbiology Reviews 39:2–16.https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12082

-

Biosynthesis of the vacuolar yeast glycoprotein carboxypeptidase YEuropean Journal of Biochemistry 85:599–608.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12275.x

-

Gene loss predictably drives evolutionary adaptationMolecular Biology and Evolution 37:2989–3002.https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa172

-

Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type 1A: expression and characterisation of wild type and mutant PMM2 in E. coliEuropean Journal of Human Genetics 7:884–888.https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200398

-

Yeast models of phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency, a congenital disorder of glycosylationG3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 9:413–423.https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.118.200934

-

Efforts to make and apply humanized yeastBriefings in Functional Genomics 15:155–163.https://doi.org/10.1093/bfgp/elv041

-

Structure of rabbit muscle phosphoglucomutase refined at 2.4 A resolutionActa Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography 53:392–405.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444997000875

-

Phosphoglucomutase kinetics with the phosphates of fructose, glucose, mannose, ribose, and galactoseThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 244:910–916.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)91872-7

-

Molecular identification of mammalian phosphopentomutase and glucose-1,6-bisphosphate synthase, two members of the alpha-D-phosphohexomutase familyThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 282:31844–31851.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M706818200

-

Altered access to beneficial mutations slows adaptation and biases fixed mutations in diploidsNature Ecology & Evolution 2:882–889.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0503-9

-

β-glucose-1,6-bisphosphate stabilizes pathological phophomannomutase2 mutants in vitro and represents a lead compound to develop pharmacological chaperones for the most common disorder of glycosylation, PMM2-CDGInternational Journal of Molecular Sciences 20:E4164.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174164

-

Identification and quantification of protein glycosylationInternational Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry 2012:1–10.https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/640923

-

The X-ray crystal structures of human alpha-phosphomannomutase 1 reveal the structural basis of congenital disorder of glycosylation type 1AThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 281:14918–14926.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M601505200

-

Induced structural disorder as a molecular mechanism for enzyme dysfunction in phosphoglucomutase 1 deficiencyJournal of Molecular Biology 428:1493–1505.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.032

-

Asp263 missense variants perturb the active site of human phosphoglucomutase 1The FEBS Journal 284:937–947.https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.14025

-

Biology, mechanism, and structure of enzymes in the α-D-phosphohexomutase superfamilyAdvances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology 109:265–304.https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apcsb.2017.04.005

-

The genomic landscape of compensatory evolutionPLOS Biology 12:e1001935.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001935

-

Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and explorationBriefings in Bioinformatics 14:178–192.https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbs017

-

Gene identification in the congenital disorders of glycosylation type I by whole-exome sequencingHuman Molecular Genetics 21:4151–4161.https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds123

-

Mammalian phosphomannomutase PMM1 is the brain IMP-sensitive glucose-1,6-bisphosphataseThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 283:33988–33993.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M805224200

-

Exploring a local genetic interaction network using evolutionary replay experimentsMolecular Biology and Evolution 38:3144–3152.https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab087

-

Protein glycosylation: new challenges and opportunitiesThe Journal of Organic Chemistry 70:4219–4225.https://doi.org/10.1021/jo050278f

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01GM127420)

- Gregory I Lang

National Institutes of Health (P20GM139769)

- Richard Steet

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Andreotti Lab and members of the Lang Lab for comments on the manuscript. We thank M Kathryn Iovine for sharing the pGEX-2T plasmid. We thank Lesa Beamer for useful discussions. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health: R01GM127420 to GIL and P20GM139769 to RS (Trudy Mackay PI/PD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by DiSTABiF, University of Campania 'Luigi Vanvitelli' (fellowship POR Campania FSE 2014/2020 'Dottorati di Ricerca Con Caratterizzazione Industriale' to MA) and the Short Term Mobility Program 2022, CNR to GA. Portions of this research were conducted on Lehigh University’s Research Computing infrastructure partially supported by the National Science Foundation (Award 2019035). Perlara PBC provided funding support for reagents and personnel time.

Copyright

© 2022, Vignogna et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,527

- views

-

- 201

- downloads

-

- 12

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 12

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79346