Gene Regulation: Blocking the blocker

Genes that code for proteins account for less than 2% of the human genome: what does the rest of the genome do? Some of it is given over to genes for RNA molecules that have vital roles in cellular processes, such as ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs and small regulatory RNAs. However, the roles of other RNA molecules – notably molecules called long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) – are not fully understood, although many lncRNAs are known to be involved in the regulation of gene transcription (Statello et al., 2021).

The non-coding part of the genome also contains regions called cis-regulatory DNA elements that orchestrate the precise timing, location and extent of gene expression (Oudelaar and Higgs, 2021). These elements include chromatin boundary elements, also known as insulators, that associate with insulator proteins to wire the genomic DNA into specific three-dimensional shapes (Phillips-Cremins and Corces, 2013). Insulators also directly regulate gene expression by separating other regulatory elements, such as enhancers and promoters.

Gene regulation means that the different cell types in a multi-cellular organism decode the same genetic information (the genome) in a cell-type-specific manner. One widely studied example of this is the regulation of hox genes, which have an important role during animal development (Hubert and Wellik, 2023). However, the precise mechanisms governing the spatial and temporal expression of hox genes are still under investigation. Now, in eLife, Airat Ibragimov, Paul Schedl and colleagues at Princeton University and the Russian Academy of Sciences report the results of experiments on Drosophila which reveal an unexpected role for lncRNAs in the regulation of hox genes (Ibragimov et al., 2023).

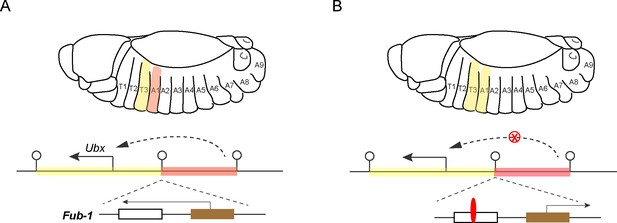

Focusing on the regulation of a hox gene called Ubx (which is short for Ultrabithorax), the researchers studied the function of Fub-1, an insulator that is positioned between the regulatory domains that determine how Ubx is expressed in two distinct body segments in Drosophila embryos (Figure 1; Castelli-Gair et al., 1992; Maeda and Karch, 2015).

Hox genes, insulators and lncRNAs.

(A) Schematic drawing of a Drosophila embryo showing thoracic and abdominal body segments (top), and the locus of the hox gene called Ubx (bottom); the solid line with the arrowhead indicates the direction of Ubx transcription. The yellow region is the regulatory domain that is responsible for specifying Ubx expression in the T3 body segment, and the orange region is the regulatory domain for the A1 body segment (dashed line with arrowhead). The Fub-1 insulator (lollipop symbol in the middle) that separates these two domains contains two sub-elements: the HS1 sub-element (white rectangle) contains a binding site for an insulator protein called CTCF, and the HS2 sub-element (brown rectangle) contains an element that promotes the transcription of a lncRNA gene (solid line with arrowhead). There is also an insulator at the other end of each regulatory domain. Ibragimov et al. have shown the activity of the Fub-1 insulator is compromised when the lncRNA in HS2 is being actively transcribed. (B) When the direction of lncRNA transcription is reversed, the interaction between the regulatory domain for A1 (orange region) and the Ubx gene is blocked (red X), presumably because the insulator protein CTCF (red) is able to bind to the HS1 element, which results in the A1 segment resembling the T3 segment.

Fub-1 has two parts: a sub-element called HS1 contains a binding site for an insulator protein, and a sub-element called HS2 promotes the transcription of a lncRNA gene (Pease et al., 2013). Ibragimov et al. employed a state-of-the-art gene replacement strategy to generate mutants in which Fub-1 had been deleted, and mutants in which Fub-1 had been modified. Surprisingly, the former appeared morphologically normal (although there were changes to the three-dimensional shapes adopted by the genomic DNA). This was unusual because depleting a classic insulator element typically results in abnormal segmental identity (Gyurkovics et al., 1990).

Further tests using mutant animals with modified Fub-1 revealed that transcription of the lncRNA promoter in HS2 counteracts the insulator activity of Fub-1. In cells where the lncRNA is actively being transcribed, this presumably happens because the presence of the molecular machinery required for transcription disrupts the binding of the insulator protein to HS1. This dual nature explains why deleting Fub-1 did not result in a change of morphology. However, when the direction of transcription is reversed, the insulator activity of Fub-1 is restored. In this case, the regulatory domain for the A1 body segment can no longer interact with the Ubx gene, which leads to defects in segment identity (Figure 1).

One puzzling point remains: why does the deletion of Fub-1 not result in any obvious phenotype? As discussed by Ibragimov et al., this element is conserved in distantly related Drosophila species, suggesting that it may be important in other species or in challenging environments, such as the wild.

While the sequence and location of insulators have been mapped in several genomes, the functions and regulation of these elements await further detailed study. The work of Ibragimov et al. elegantly illustrates the multifaceted role of insulators (and lncRNAs), and the complexity of their function. Moreover, although it was carried out in Drosophila, their work has broader implications as the function, regulation and chromosomal clustering of many hox genes are evolutionarily conserved, so similar mechanisms may be at play in other animal species.

References

-

Positive and negative cis-regulatory elements in the bithoraxoid region of the Drosophila Ultrabithorax geneMolecular & General Genetics 234:177–184.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00283837

-

The relationship between genome structure and functionNature Reviews Genetics 22:154–168.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-00303-x

-

Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functionsNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 22:96–118.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-00315-9

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Dai

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 507

- views

-

- 37

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.