Post-translational Modifications: Reversing ADP-ribosylation

Cells rapidly react to stimuli in their environment by making modifications to proteins that change the way those proteins interact with other molecules (Mann and Jensen, 2003). Once a stimulus has stopped, these 'post-translational modifications' are usually reversed and the cell’s life goes back to normal. For example, when a cell suffers damage to its DNA, the addition of a molecule called ADP-ribose – a process that is known as ADP-ribosylation – to certain proteins sends a signal that leads to the damage being repaired; drugs that inhibit the addition of ADP-ribose are also used in cancer therapy (see Li and Yu, 2015 for a review).

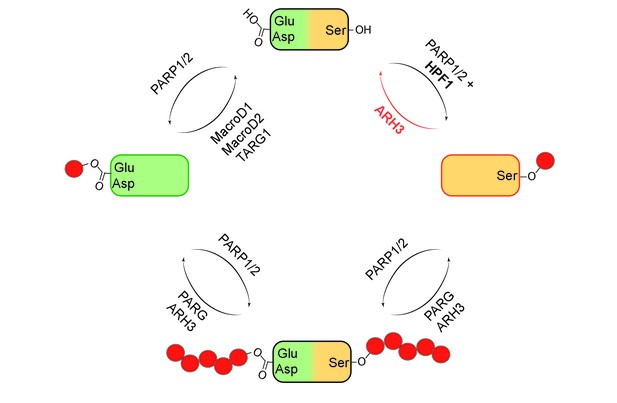

It was discovered in the 1960s that specialized enzymes called PARPs can add one or more units of ADP-ribose (ADPr) to specific amino acids within proteins. Over the decades, it became clear that these enzymes are involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including DNA repair, transcription, chromatin regulation and cell death. The first target sites for ADP-ribosylation to be identified were mostly glutamates, aspartates and lysines, and the enzymes responsible for the removal of the ADPr units were also established (Figure 1)(Barkauskaite et al., 2013).

Mono- and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and their reversal.

When a protein (top) undergoes mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation the ADP-ribose (red circle) can be added to a glutamate (Glu) or aspartate (Asp; left) or a serine (Ser; right). It is also possible for multiple units of ADP-ribose to be added to a protein at a given target site in a process known as poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (bottom). The enzymes PARP1 and PARP2 are involved in ADP-ribosylation of both Glu/Asp and Ser, with a protein called HPF1 acting as a cofactor in the mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation of Ser. The enzymes involved in the reversal of both mono- and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation are shown. Fontana et al. have shown that ARH3 is exclusively responsible for reversing the mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation of Ser, and that it is also involved (with PARG) in reversing the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of Ser.

More recently, it was shown that serines can be target sites for ADP-ribosylation, and that many of the proteins that contain such target sites have important roles in DNA damage repair (Bilan et al., 2017; Bonfiglio et al., 2017; Leidecker et al., 2016; Gibbs-Seymour et al., 2016). However, nothing was known about the enzymes or mechanisms responsible for the removal of the ADPr units from the serines. Now, in eLife, Ivan Ahel of the University of Oxford, Ivan Matic of the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing in Cologne and co-workers – including Pietro Fontana, Juan José Bonfiglio and Luca Palazzo as joint first authors, along with Edward Bartlett – provide new insight into these matters (Fontana et al., 2017).

Using biochemical approaches and a technique called mass spectrometry, Fontana et al. screened a number of proteins that are known to bind to ADPr to find out if they could remove ADPr units that had been added to serines. They discovered that an enzyme called ARH3 could remove ADPr from serine on histone proteins (Figure 1). Previous research has shown that ARH3 and PARG work in similar ways. Both enzymes are able to break the ribose bonds that hold chains of ADPr units together, but ARH3 hydrolyses the chains less efficiently than PARG and also has a different structure (Mueller-Dieckmann et al., 2006; Oka et al., 2006). Fontana et al. discovered that unlike PARG, ARH3 was able to cleave both single ADPr units and chains of ADPr on histones and other proteins.

Since mass spectrometry is a rather expensive and laborious technique, Fontana et al. also used ARH3 in combination with western blotting – a basic technique to detect specific proteins or protein modifications – to track ADP-ribosylation on serines. These experiments confirmed the findings obtained with mass spectrometry, and proved that histone proteins are primarily – if not exclusively – modified on serine. Future studies could build on these findings and use ARH3 as a tool to detect the ADP-ribosylation of serines in proteins.

Despite these new insights, many outstanding questions remain. For example, how does adding ADPr to serine affect the role of a protein? And what happens when two neighboring amino acids experience post-translational modifications? A widely studied post-translational modification that regulates gene expression involves the methylation or acetylation of two lysines (K9 and K27) in histone three (Saksouk et al., 2015). However, these lysines are followed by a serine, which could undergo its own post-translation modification (which could be phosphorylation or ADP-ribosylation). Would these modifications influence each other? Probably, yes. This complex interplay may have far reaching consequences in the regulation of gene expression, and may play an important role in many diseases that depend on ADP-ribosylation pathways.

References

-

The recognition and removal of cellular poly(ADP-ribose) signalsFEBS Journal 280:3491–3507.https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.12358

-

Serine ADP-ribosylation depends on HPF1Molecular Cell 65:932–940.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.003

-

Serine is a new target residue for endogenous ADP-ribosylation on histonesNature Chemical Biology 12:998–1000.https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2180

-

Proteomic analysis of post-translational modificationsNature Biotechnology 21:255–261.https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0303-255

-

Identification and characterization of a mammalian 39-kDa poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolaseJournal of Biological Chemistry 281:705–713.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M510290200

-

Constitutive heterochromatin formation and transcription in mammalsEpigenetics & Chromatin 8:3.https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8935-8-3

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2017, Moeller et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,274

- views

-

- 145

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cancer Biology

Cancer cells display high levels of oncogene-induced replication stress (RS) and rely on DNA damage checkpoint for viability. This feature is exploited by cancer therapies to either increase RS to unbearable levels or inhibit checkpoint kinases involved in the DNA damage response. Thus far, treatments that combine these two strategies have shown promise but also have severe adverse effects. To identify novel, better-tolerated anticancer combinations, we screened a collection of plant extracts and found two natural compounds from the plant, Psoralea corylifolia, that synergistically inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Bakuchiol inhibited DNA replication and activated the checkpoint kinase CHK1 by targeting DNA polymerases. Isobavachalcone interfered with DNA double-strand break repair by inhibiting the checkpoint kinase CHK2 and DNA end resection. The combination of bakuchiol and isobavachalcone synergistically inhibited cancer cell proliferation in vitro. Importantly, it also prevented tumor development in xenografted NOD/SCID mice. The synergistic effect of inhibiting DNA replication and CHK2 signaling identifies a vulnerability of cancer cells that might be exploited by using clinically approved inhibitors in novel combination therapies.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Stem cell differentiation involves a global increase in protein synthesis to meet the demands of specialized cell types. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this translational burst and the involvement of initiation factors remains largely unknown. Here, we investigate the role of eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) in early differentiation of human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs). Using Quick-irCLIP and alternative polyadenylation (APA) Seq, we show eIF3 crosslinks predominantly with 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR) termini of multiple mRNA isoforms, adjacent to the poly(A) tail. Furthermore, we find that eIF3 engagement at 3’-UTR ends is dependent on polyadenylation. High eIF3 crosslinking at 3’-UTR termini of mRNAs correlates with high translational activity, as determined by ribosome profiling, but not with translational efficiency. The results presented here show that eIF3 engages with 3’-UTR termini of highly translated mRNAs, likely reflecting a general rather than specific regulatory function of eIF3, and supporting a role of mRNA circularization in the mechanisms governing mRNA translation.