The nutrient-sensing GCN2 signaling pathway is essential for circadian clock function by regulating histone acetylation under amino acid starvation

Abstract

Circadian clocks are evolved to adapt to the daily environmental changes under different conditions. The ability to maintain circadian clock functions in response to various stresses and perturbations is important for organismal fitness. Here, we show that the nutrient-sensing GCN2 signaling pathway is required for robust circadian clock function under amino acid starvation in Neurospora. The deletion of GCN2 pathway components disrupts rhythmic transcription of clock gene frq by suppressing WC complex binding at the frq promoter due to its reduced histone H3 acetylation levels. Under amino acid starvation, the activation of GCN2 kinase and its downstream transcription factor CPC-1 establish a proper chromatin state at the frq promoter by recruiting the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5. The arrhythmic phenotype of the GCN2 kinase mutants under amino acid starvation can be rescued by inhibiting histone deacetylation. Finally, genome-wide transcriptional analysis indicates that the GCN2 signaling pathway maintains robust rhythmic expression of metabolic genes under amino acid starvation. Together, these results uncover an essential role of the GCN2 signaling pathway in maintaining the robust circadian clock function in response to amino acid starvation, and demonstrate the importance of histone acetylation at the frq locus in rhythmic gene expression.

Editor's evaluation

This fundamental work is important in demonstrating that the general amino acid control response to amino acid limitation in Neurospora, which includes the key nutrient-controlled protein kinase Gcn2, is crucial to maintain circadian rhythmic cell growth and transcription of the FRQ gene, the master regulator of rhythmicity. There is an abundance of compelling evidence supporting the conclusions, with rigorous molecular and genetic assays of key mutants impaired for general amino acid control or transcriptional cofactors. The work will be of broad interest to geneticists and molecular biologists, and will be particularly valuable to researchers interested in circadian rhythm or nutrient control of gene expression.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.85241.sa0Introduction

Circadian clocks enable organisms to adapt to the daily environmental changes caused by the earth’s rotation (Bell-Pedersen et al., 2005; Dunlap and Loros, 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; Takahashi, 2017). Rhythmic gene expression allows different organisms to regulate their daily molecular, cellular, behavioral, and physiological activities. The ability to maintain circadian clock function in response to various stresses and perturbations is an important property of living systems (Bass, 2012; Hogenesch and Ueda, 2011). Although gene expression is sensitive to temperature changes, temperature compensation is a key feature of circadian clocks to maintain circadian period length at different physiological temperatures (Hu et al., 2021; Narasimamurthy and Virshup, 2021; Ode and Ueda, 2018). DNA damage and translation stress are known to reset the circadian clock through the checkpoint kinase 2 signaling pathway in Neurospora and the ATM signaling pathway in mammalian cells (Diernfellner et al., 2019; Oklejewicz et al., 2008; Pregueiro et al., 2006). Cellular redox balance, including oxidative stress, regulates the circadian clock by modulating CLOCK and NPAS2 activity (Nakahata et al., 2008; Rutter et al., 2001). Nutritional stress, such as a high-fat diet, can disrupt the oscillating metabolites and behavioral rhythms in mice (Eckel-Mahan et al., 2013; Kohsaka et al., 2007; Panda, 2016).

Starvation for all or certain amino acids leads to induced transcription followed by derepression of genes in many amino acid biosynthetic pathways, referred as general amino acid control in yeast and cross-pathway control (CPC) in Neurospora (Hinnebusch, 2005). General control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) kinase, called CPC-3 in Neurospora, is a serine/threonine kinase that functions as an amino acid sensor (Battu et al., 2017; Efeyan et al., 2015; Sattlegger et al., 1998). GCN2 is activated by accumulated uncharged tRNAs when intracellular amino acids are limited (Ramirez et al., 1992; Wek et al., 1995). Activated GCN2 phosphorylates the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) to translationally repress protein synthesis (Lyu et al., 2021; Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009). Meanwhile, it also upregulates the transcription activator GCN4, named CPC-1 in Neurospora, which activates amino acid biosynthetic and transport pathways (Ebbole et al., 1991; Hinnebusch, 2005). Recently, it has been shown that circadian clock control of the GCN2-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation is necessary for rhythmic translation initiation in Neurospora (Ding et al., 2021; Karki et al., 2020). Although amino acid starvation is known to activate the GCN2–GCN4 signaling pathway, how nutrient limitation, especially amino acid starvation, affects circadian clock is not known.

Despite evolutionary divergence in eukaryotes, circadian rhythms are controlled by the conserved transcription/translation-based negative feedback loops (Bell-Pedersen et al., 2005). Neurospora crassa has been established as one of the best studied model systems for analyzing the molecular mechanism of eukaryotic circadian clocks (Cha et al., 2015; Dunlap and Loros, 2017; Heintzen and Liu, 2007). In the Neurospora core circadian negative feedback loop, two PAS-domain-containing transcription factors, White Collar-1 (WC-1) and WC-2 form a complex (WCC) and bind to the C-box of the frq promoter to activate its transcription (Cheng et al., 2001b; Crosthwaite et al., 1997; Froehlich et al., 2002). FRQ protein is translated from frq mRNA in the cytosol and progressively phosphorylated at about 103 phosphorylation sites, which plays a major role in determining circadian periodicity by regulating the FRQ–CK1 interaction (Baker et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2023; Larrondo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2009). To close the negative feedback loop, FRQ forms a complex with its partner FRQ-interacting RNA helicase (FRH) to inhibit the activity of the WCC by promoting WCC phosphorylation mediated by CK1 and CK2 (He et al., 2006; He and Liu, 2005; Schafmeier et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019).

Chromatin structure and histone modification changes play important roles in regulating the transcription of circadian clock genes (Papazyan et al., 2016; Takahashi, 2017; Zhu and Belden, 2020). In mammals, rhythmic H3K4me3, H3K9ac, and H3K27ac modifications have been shown to be enriched at the promoter of clock genes and positively correlated with gene expression (Etchegaray et al., 2003; Katada and Sassone-Corsi, 2010; Koike et al., 2012). In Neurospora, rhythmic binding of WCC to the frq promoter is regulated by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factors, such as the SWI/SNF complex, the INO80 complex, the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding-1 (CHD1), and the Clock ATPase (CATP) (Belden et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2013; Gai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). Histone chaperone FACT complex and histone modification enzymes, SET1, SET2, and RPD3 complex, have also been shown to affect frq transcription by regulating rhythmic histone compositions and modifications at the frq locus (Liu et al., 2017; Raduwan et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2016). However, it is still unknown how the chromatin structure is organized to allow rhythmic clock gene expression under nutrient limitation conditions.

In this study, we discovered that the disruption of the GCN2 (CPC-3) signaling pathway abolished robust circadian rhythms under amino acid starvation, which was important for rhythmic expression of metabolic genes. In the GCN2 signaling pathway mutants, amino acid starvation abolished the rhythmic binding of WC-2 at the frq promoter by decreasing its histone H3 acetylation levels. Amino acid starvation activated CPC-3 and CPC-1, which re-established a proper chromatin state at the frq promoter by recruiting the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5 to allow rhythmic frq expression. Furthermore, the inhibition of histone deacetylases could rescue the impaired circadian rhythm phenotypes under amino acid starvation, demonstrating the importance of rhythmic histone acetylation at the frq gene promoter for maintaining robust circadian rhythms of gene expression.

Results

CPC-3 and CPC-1 are required for robust circadian rhythms under amino acid starvation

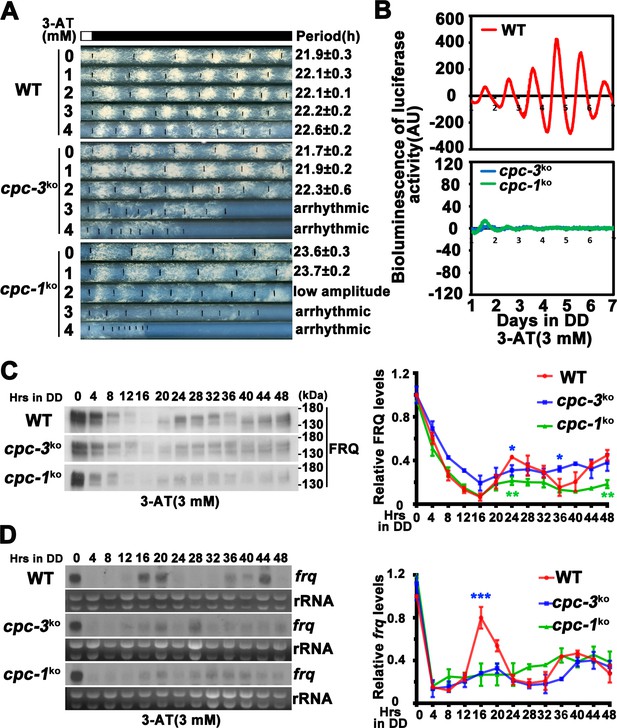

To investigate whether the nutrient-sensing GCN2 pathway is involved in regulating circadian clock function under amino acid starvation, we created the cpc-3 and cpc-1 knockout mutants (see Materials and methods). In Neurospora, cpc-3 and cpc-1 encode for the GCN2 and GCN4 homolog, respectively. As expected, the CPC-3-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation and CPC-1 induction by 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) treatment were completely abolished in the cpc-3KO strain (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). 3-AT is an inhibitor of the histidine synthesis enzyme encoded by his-3 which triggers the amino acid starvation response (Natarajan et al., 2001). On the other hand, CPC-1 expression and its induction by 3-AT were eliminated in the cpc-1KO mutant (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). The circadian conidiation rhythms of the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO mutants were examined by race tube assays. Under a normal growth condition (0 mM 3-AT), cpc-3 deletion had no effect on the circadian period but cpc-1 deletion led to the period lengthening of ~1.7 hr (Figure 1A). The long period of cpc-1KO strain could be rescued by the expression of Myc.CPC-1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C).

CPC-3 and CPC-1 are required for circadian rhythm by regulating rhythmic frq transcription in response to amino acid starvation.

(A) Race tube assay showing that amino acid starvation (3-aminotriazole [3-AT] treatment) disrupted circadian conidiation rhythm of the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains. 0 mM 3-AT is the normal growth condition. (B) Luciferase reporter assay showing that amino acid starvation disrupted rhythmic expression of frq promoter-driven luciferase of the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains. A frq-luc transcriptional fusion construct was expressed in cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains grown on the fructose-glucose-sucrose FGS-Vogel’s medium with the indicated concentrations of 3-AT, and the luciferase signal was recorded using a LumiCycle in constant darkness (DD) for more than 7 days. Normalized data with the baseline luciferase signals subtracted are shown. (C) Western blot showing that amino acid starvation dampened rhythmic expression of FRQ protein of the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains at the indicated time points in DD (n = 3; WT: p = 5.00E−08, cpc-3KO: p = 0.0016, cpc-1KO: p = 0.0004, RAIN; WT vs cpc-3KO: mesor p = 0.1421, amplitude p = 0.0774, phase p = 0.4319; WT vs cpc-1KO: mesor p = 0.0614, amplitude p = 0.1920, phase p = 0.4404, CircaCompare). The left panel showing that protein extracts were isolated from WT, cpc-3KO, and cpc-1KO strains grown in a circadian time course in DD and probed with FRQ antibody. The right panel showing that the densitometric analyses of the results of three independent experiments. (D) Northern blot showing that amino acid starvation dampened rhythmic expression of frq mRNA of the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains at the indicated time points in DD (n = 3; WT: p = 6.56E−05, cpc-3KO: p = 0.0039, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05, RAIN; WT vs cpc-3KO: mesor p = 0.1153, amplitude p = 0.4316, phase p = 0.0788, CircaCompare). The densitometric analyses of the results from three independent experiments were shown on the right panel. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test was used.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

LumiCycle analysis dataset in Figure 1B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig1-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—source data 2

Scan of western blot probed for FRQ protein and quantification dataset in Figure 1C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig1-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—source data 3

Scan of Northern blot probed for frq mRNA and quantification dataset in Figure 1D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig1-data3-v2.zip

To investigate how amino acid starvation affects circadian clock, we treated the wild-type (WT), cpc-3KO, and cpc-1KO strains with different concentrations of 3-AT. As shown in Figure 1A, although treatment with 3 or 4 mM 3-AT resulted in modest inhibition of the WT growth rate, the robust circadian conidiation rhythms were maintained. In the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains, however, addition of 3 or 4 mM 3-AT resulted in severe inhibition of growth rates and the loss of circadian conidiation rhythms. To exclude the effect of 3-AT on other target genes, we examined the circadian rhythm of the his-3− strain, which contained a single mutation in the his-3 gene required for histidine synthesis and could not grow in the medium without histidine. Race tube assays showed that the his-3− strain grew normally and exhibited a robust circadian conidiation rhythm in the presence of histidine (1.0 × 10−2 mg/ml). Although addition of the same amount of histidine could rescue the growth of the cpc-3KO his-3− strain, it could not rescue its circadian conidiation rhythm (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D), indicating that CPC-3 is required for robust circadian rhythms under histidine starvation stress.

To confirm the loss of circadian rhythms at the molecular level, we introduced a frq promoter-driven luciferase reporter into the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains. As shown in Figure 1B and Figure 1—figure supplement 2A, B, the robust circadian rhythms of luciferase activity seen in the WT strain were severely dampened or arrhythmic in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains upon 3 mM 3-AT treatment. Consistent with these results, western blot analysis showed that, after the initial light/dark transition, rhythms of FRQ levels and its phosphorylation were dampened in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains in the presence of 3-AT (WT: p = 5.00E−08, cpc-3KO: p = 0.0016, cpc-1KO: p = 0.0004) (Figure 1C and Figure 1—figure supplement 2C). The statistical tests of circadian rhythms were performed using a circadian statistical analysis tool CircaCompare (Parsons et al., 2020) (see Materials and methods). Northern blot analysis showed that the circadian rhythms of frq mRNA in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains were also dampened in the presence of 3-AT (WT: p = 6.56E−05, cpc-3KO: p = 0.0039, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) and the levels of frq mRNA were constantly low in DD (Figure 1D and Figure 1—figure supplement 2D). Together, these results suggest that the GCN2 pathway is required for a functional clock by regulating rhythmic frq transcription in response to amino acid starvation.

CPC-3 and CPC-1 are required for rhythmic WCC binding in response to amino acid starvation

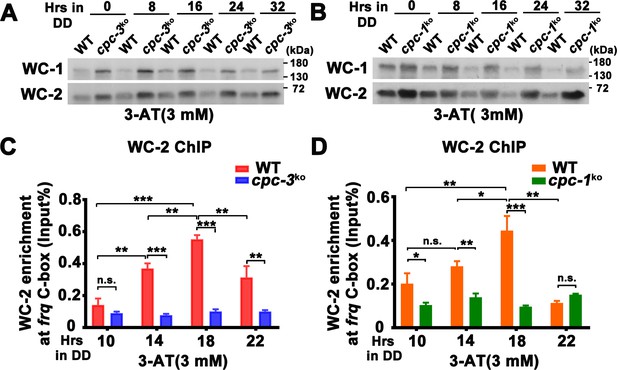

Since 3-AT treatment resulted in low frq mRNA levels in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains (Figure 1D), we first examined the protein levels of WC-1 and WC-2 and found that their levels were higher in the mutants than those in the WT strain at different time points (Figure 2A, B). We then performed WC-2 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to examine whether the WCC binding to the frq promoter was affected. As shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 1A, WC-2 rhythmically bound to the frq C-box in the WT, cpc-3KO, and cpc-1KO strains without 3-AT treatment (WT: p = 2.60E−07, cpc-3KO: p = 0.0016, cpc-1KO: p = 1.06E−05). However, 3-AT treatment resulted in constant low levels of WC-2 binding to the frq C-box during a circadian cycle in both cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains (Figure 2C, D). These results indicate that the loss of circadian rhythms in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains under amino acid starvation is caused by loss of rhythmic frq transcription, due to impaired WCC binding at the frq promoter.

CPC-3 and CPC-1 are required for rhythmic WCC binding in response to amino acid starvation.

Western blot assay showing that WCC protein levels were elevated in the cpc-3KO (A) and cpc-1KO (B) strains after 3 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) treatment. Protein extracts were isolated from WT, cpc-3KO, and cpc-1KO strains grown in the indicated time points in DD and probed with WC-1 and WC-2 antibodies. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showing that amino acid starvation disrupted rhythmic WC-2 binding at the promoter of frq gene in the cpc-3KO (n = 3; WT: p = 1.84E−05, cpc-3KO: p > 0.05) (C) or cpc-1KO strains (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0025, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) (D). Samples were grown for the indicated number of hours in DD prior to harvesting and processing for ChIP using WC-2 antibody. Occupancies were normalized by the ratio of ChIP to Input DNA. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test was used.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Scan of western blot probed for WC-1 and WC-2 proteins in WT and cpc-3KO strains with 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) in Figure 2A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig2-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Scan of western blot probed for WC-1 and WC-2 proteins in WT and cpc-1KO strains with 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) in Figure 2B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig2-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 3

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 2C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig2-data3-v2.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 4

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 2D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig2-data4-v2.zip

Because WCC phosphorylation inhibited its transcriptional activation activity (He et al., 2006; He and Liu, 2005; Lee et al., 2000; Schafmeier et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019), we also examined WCC phosphorylation profiles and found that 3-AT treatment resulted in hypophosphorylation of WC-1 and WC-2 (which is usually associated with WCC activation) in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO strains (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B, C). Thus, their reduced WCC binding at the frq promoter is not caused by WCC hyperphosphorylation. It should be noted that the overall phosphorylation status of WCC does not always reflect its activity in driving frq transcription, which is possibly due to the unknown function of multiple key phosphosites on WCC (Wang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018).

CPC-1 is required for the maintenance of chromatin structure in response to amino acid starvation

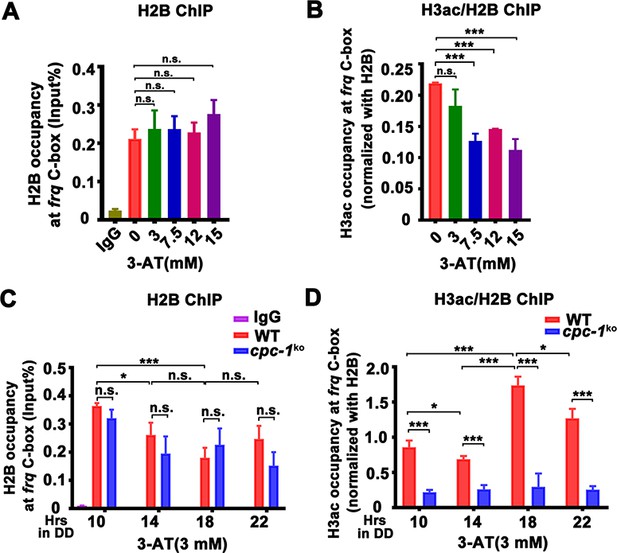

The low WC-2 binding at the frq promoter prompted us to examine the chromatin structure of the frq promoter. We first performed ChIP assay to examine the histone and its acetylation levels at the frq promoter in the WT strain. Although amino acid starvation had little effect on the histone H2B levels (Figure 3A), it led to significantly decreased histone H3 acetylation levels (H3 acetylated at the N-terminus) at the frq promoter at high concentrations of 3-AT (Figure 3B). These results suggest that amino acid starvation can affect frq transcription by reducing the histone acetylation levels at the frq promoter.

CPC-1 is required for the maintenance of chromatin structure in response to amino acid starvation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showing that amino acid starvation slightly increased histone H2B levels (A) and dramatically decreased histone H3ac levels (B) at the promoter of frq gene in the WT strain at DD18 at the indicated concentration of 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). Relative H3ac levels were normalized with H2B levels. (C, D) ChIP assay showing that amino acid starvation slightly increased histone H2B levels (n = 3; WT: p = 3.85E−04, cpc-1KO: p = 0.0364, RAIN; WT vs cpc-1KO: mesor p = 0.0312, amplitude p = 0.2155, phase p = 0.2995, CircaCompare) (C) and dramatically decreased histone H3ac levels (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0168, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) (D) at the promoter of frq gene in the cpc-1KO strain at the indicated time points in DD. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test was used.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 3A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig3-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 3B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig3-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 3

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 3C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig3-data3-v2.zip

-

Figure 3—source data 4

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 3D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig3-data4-v2.zip

We then examined whether the CPC-3 and CPC-1 signaling pathway was involved in regulating chromatin structure at the frq promoter in response to amino acid starvation. Histone H2B and H3ac ChIP assays at different circadian time points showed that the relative histone H3ac levels were slightly decreased in the cpc-1KO strain compared to the WT strain under normal condition (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D). H2B levels were not markedly different between the WT and cpc-1KO strains in the presence of 3 mM 3-AT (Figure 3C). However, the relative histone H3ac levels were very different in these two strains in the presence of 3 mM 3-AT: it was rhythmic with a peak at DD18 in the WT strain but was dramatically reduced and arrhythmic in the cpc-1KO strain at different time points in DD (WT: p = 0.0168, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) (Figure 3D). These results indicate that CPC-1 is required for maintaining the proper histone acetylation status at the frq promoter under amino acid starvation. The low H3ac levels at the frq promoter, which is critical for transcription activation, results in constant low WCC binding and arrhythmic frq transcription in the cpc-1KO strain.

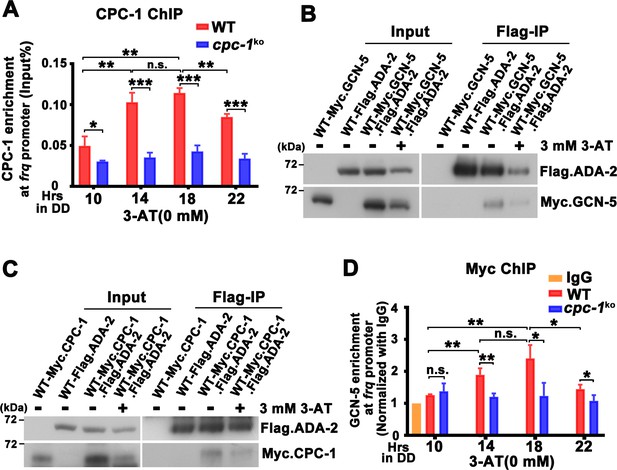

CPC-1 recruits GCN-5 to activate frq transcription in response to amino acid starvation

To determine how CPC-1 is involved in regulating histone acetylation levels at the frq locus, we examined the occupancy of CPC-1 at the frq promoter by ChIP assays using CPC-1 antibody. As shown in Figure 4A and Figure 4—figure supplement 1A, CPC-1 was found to be rhythmically enriched at the frq promoter in the WT strain but not in the cpc-1KO strain under normal (WT: p = 8.37E−06, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) or amino acid starvation (WT: p = 7.64E−05) conditions in DD, peaking at ~DD14, a time point corresponding to the peak of frq mRNA levels. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay showed that CPC-1 did not associate with WC-1 or WC-2 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1B), suggesting that CPC-1 and WCC bind independently to the frq promoter.

CPC-1 recruits GCN-5 to activate frq transcription in response to amino acid starvation.

(A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showing that CPC-1 rhythmically bound at the promoter of frq gene (n = 3; WT: p = 8.37E−06, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05). WT and cpc-1KO strains grown for the indicated number of hours in DD. Samples were crosslinked with formaldehyde and harvested for ChIP using CPC-1 antibody. CPC-1 ChIP occupancies were normalized by the ratio of ChIP to Input DNA. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay showing that Flag.ADA-2 interacted with Myc.GCN-5 with or without 3 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). Flag.ADA-2 and Myc.GCN-5 were co-expressed in the WT strain and immunoprecipitation was performed using Flag antibody. (C) Co-IP assay showing that Flag.ADA-2 interacted with Myc.CPC-1 with or without 3 mM 3-AT. Flag.ADA-2 and Myc.CPC-1 were co-expressed in the WT strain and immunoprecipitation was performed using Flag antibody. (D) ChIP assay showing that rhythmic GCN-5 binding at the promoter of frq gene was dampened in the cpc-1KO strain (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0006, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05). Samples were grown for the indicated number of hours in DD prior to harvesting and processing for ChIP as described in (A). Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test was used.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 4A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig4-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 4—source data 2

Scan of western blot probed for Flag.ADA-2 and Myc.GCN-5 proteins in Figure 4B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig4-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 4—source data 3

Scan of western blot probed for Flag.ADA-2 and Myc.CPC-1 proteins in Figure 4C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig4-data3-v2.zip

-

Figure 4—source data 4

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 4D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig4-data4-v2.zip

How does the GCN2 signaling pathway regulate histone acetylation in response to amino acid starvation? The yeast GCN4 was previously shown to recruit the histone acetyltransferase GCN5 containing (Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase) SAGA complex to selective gene promoters, likely through its physical interaction with the ADA2 subunit (Barlev et al., 1995; Drysdale et al., 1998; Kuo et al., 2000). To test this possibility, we performed Co-IP assay to check the interaction between CPC-1 and the SAGA complex in Neurospora in strains expressing the epitope-tagged Neurospora SAGA homologs. As shown in Figure 4B, Myc-tagged GCN-5 was efficiently immunoprecipitated by the Flag-tagged ADA-2, indicating the existence of an SAGA complex in Neurospora. Although the Myc.GCN-5, MYC.CPC-1 or Flag.ADA-2 protein levels were repressed by 3 mM 3-AT treatment (potentially due to global translational inhibition by eIF2α phosphorylation) (Karki et al., 2020), the interaction between GCN-5 and ADA-2 was almost the same under either normal or amino acid starved conditions (IP was normalized with Input). Importantly, Myc.CPC-1 was also found to associate specifically with Flag.ADA-2 with/without 3-AT treatment (Figure 4C), suggesting that CPC-1 can recruit the SAGA complex to the frq promoter through its ADA-2 subunit to regulate histone acetylation levels at the frq locus under normal or amino acid starvation conditions. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation assays showed that WC-1 and WC-2 also interacted with Myc.GCN-5 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1C). These results suggest that CPC-1 can regulate histone acetylation by recruiting the SAGA complex to the frq promoter.

To further confirm if CPC-1 can recruit GCN5 to the frq promoter, we performed ChIP assay to examine the occupancy of GCN-5 at the frq promoter. As shown in Figure 4D, Myc-tagged GCN-5 rhythmically bound at the frq promoter in DD in the WT strain but its binding was constantly low and arrhythmic in the cpc-1KO strain (WT: p = 0.0006, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05), suggesting that CPC-1 recruits the GCN-5 containing SAGA complex to the frq promoter to allow rhythmic histone acetylation levels, which maintain rhythmic WC-2 binding and thus rhythmic frq transcription.

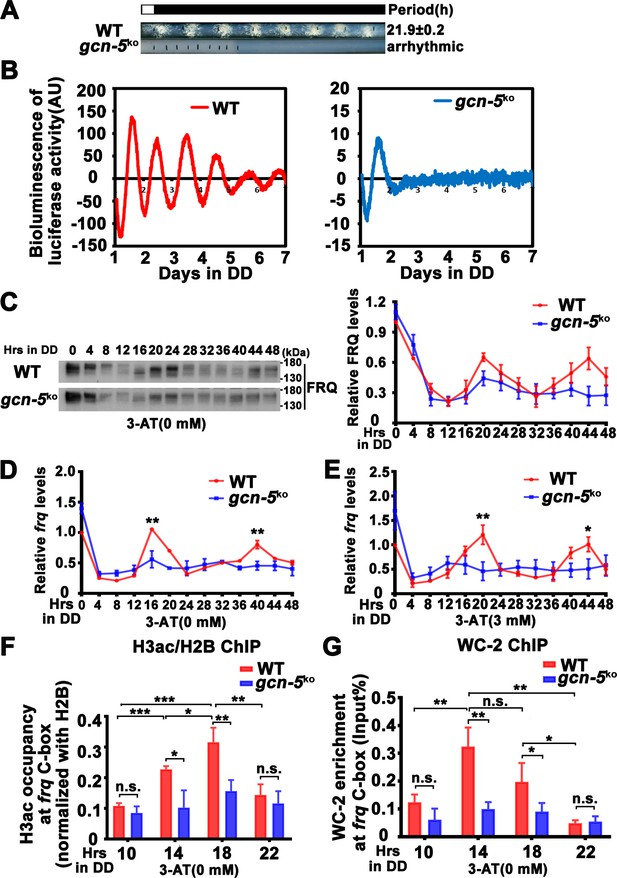

GCN-5 is required for rhythmic H3ac at the frq promoter

GCN-5 has been shown to regulate light induction and oxidative stress response in Neurospora (Grimaldi et al., 2006; Qi et al., 2018), but its role in the circadian clock remains unclear. To determine the function of GCN-5 in the circadian clock, we created the gcn-5 knockout mutant, and found that it exhibited slow growth and lacked a conidiation rhythm (Figure 5A). To determine its circadian clock at the molecular level, we introduced the FRQ-LUC reporter (luciferase fused at the C terminus of the FRQ protein) into the gcn-5KO strain (Larrondo et al., 2015). As shown in Figure 5B and Figure 5—figure supplement 1B, a robust circadian rhythm of luciferase activity was observed in the WT strain, but it was quickly dampened after 1 day in DD and became arrhythmic in the gcn-5KO strain. Western blot analysis showed that, after the initial light/dark transition, the rhythmic FRQ abundance and phosphorylation were significantly dampened in the gcn-5KO mutant (WT: p = 5.00E−8, gcn-5KO: p = 0.0016) (Figure 5C). Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR RT-qPCR analysis showed that the circadian rhythms of frq mRNA were also severely dampened in the gcn-5KO strain without (WT: p = 8.37E−06, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05) or with 3 mM 3-AT (WT: p = 5.39E−12, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05) (Figure 5D, E). Together, these results indicate that GCN-5 is critical for maintaining the function of circadian clock.

GCN-5 is required for rhythmic chromatin structure changes at the frq promoter.

(A) Race tube assay showing that the conidiation rhythm in gcn-5KO strain was lost compared with WT strain. (B) Luciferase assay showing that the luciferase activity rhythm was impaired in the gcn-5KO strain after 1 day transition from light to dark. A FRQ-LUC translational fusion construct was expressed in WT and gcn-5KO strains, and the luciferase signal was recorded in DD for more than 7 days. Normalized data with the baseline luciferase signals subtracted are shown. (C) Western blot assay showing that rhythmic expression of FRQ protein was dampened in the gcn-5KO strain (n = 3; WT: p = 5.00E−08, gcn-5KO: p = 0.0016, RAIN; WT vs gcn-5KO: mesor p = 0.1421, amplitude p = 0.0774, phase p = 0.4319, CircaCompare). RT-qPCR analysis showing that rhythmic expression of frq mRNA was dampened in the gcn-5KO strain without 3-aminotriazole (3-AT; n = 3; WT: p = 8.37E−06, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05) (D) or with 3-AT (n = 3; WT: p = 5.39E−12, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05) (E). (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showing decreased histone H3ac levels at the promoter of frq gene in the gcn-5KO strain at the indicated time points in DD (n = 3; WT: p = 8.10E−05, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05). Relative H3ac levels were normalized with H2B levels. (G) ChIP assay showing decreased WC-2 levels at the promoter of frq gene in the gcn-5KO strain at the indicated time points in DD (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0003, gcn-5KO: p = 0.0459, RAIN; WT vs gcn-5KO: mesor p = 0.2939, amplitude p = 0.0010, phase p = 0.6933, CircaCompare). Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test was used.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

LumiCycle analysis dataset in Figure 5B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 5—source data 2

Scan of western blot probed for FRQ protein and quantification dataset in Figure 5C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 5—source data 3

RT-qPCR analysis dataset in Figure 5D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data3-v2.zip

-

Figure 5—source data 4

RT-qPCR analysis dataset in Figure 5E.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data4-v2.zip

-

Figure 5—source data 5

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 5F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data5-v2.zip

-

Figure 5—source data 6

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis dataset in Figure 5G.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig5-data6-v2.zip

ChIP assay results showed that the H3ac levels were significantly decreased at the frq promoter, and their rhythmic occupancies were severely dampened in the gcn-5KO strain compared with the WT strain (WT: p = 8.10E−05, gcn-5KO: p > 0.05) (Figure 5F). Furthermore, the rhythmic WC-2 binding at the frq C-box of the WT strain was dramatically reduced in the gcn-5KO strain in DD (WT: p = 0.0003, gcn-5KO: p = 0.0459) (Figure 5G). These results indicate that GCN-5 is critical for circadian clock function by regulating rhythmic chromatin structure changes to allow rhythmic WC-2 binding at the frq promoter to drive rhythmic frq transcription.

Since ADA-2 interacts with GCN-5 and it is a subunit of the SAGA complex, we also created the Neurospora ada-2 knockout mutant and examined the function of ADA-2 in the circadian clock. As expected, we found that the circadian phenotypes and frq expression of the ada-2KO strain were very similar to those of the gcn-5KO strain (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A–F). Together, these results demonstrate the importance of GCN-5 and ADA-2 in the Neurospora circadian clock function.

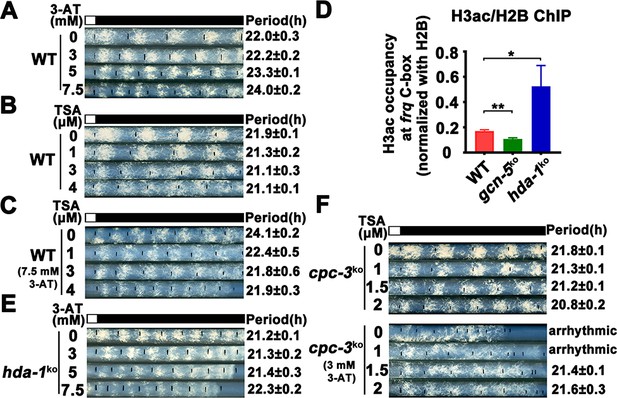

Elevated histone acetylation partially rescues circadian clock defects caused by amino acid starvation

Our results above suggest that amino acid starvation results in low histone acetylation levels at the frq promoter, which impairs the WC-2 binding and rhythmic frq transcription in the cpc-3KO and cpc-1KO mutants. To further confirm this conclusion, we hypothesized that the circadian clock defects under amino acid starvation should be rescued by increasing the histone acetylation levels. Trichostatin A (TSA) is a histone deacetylase (HDACs) inhibitor, which can inhibit HDACs activity and increase the histone acetylation levels in Neurospora (Selker, 1998). We treated the WT strain with different concentrations of 3-AT and TSA, and found that high concentrations of 3-AT lengthened the circadian period of the WT strain to ~24 hr (Figure 6A), but high concentrations of TSA resulted in a slight period shortening to 21 hr (Figure 6B). When TSA was used together with a high concentration of 3-AT (7.5 mM), the long period phenotype can be gradually rescued by increasing TSA concentrations (Figure 6C), which is consistent with our conclusion that the histone acetylation levels changes are responsible for the circadian clock defects caused by amino acid starvation.

Elevated histone acetylation partially rescues impaired circadian rhythm caused by amino acid starvation stress.

(A) Race tube assay showing that high concentrations of 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) treatment elongated circadian conidiation period of WT strain. (B) Race tube assay showing that the high concentrations of Trichostatin A (TSA) treatment shortened circadian conidiation period of WT strain. (C) TSA treatment rescued prolonged circadian period of WT strain caused by 3-AT treatment. WT strain was grown on the race tube medium containing 7.5 mM 3-AT and indicated concentrations of TSA in DD. (D) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showing that H3ac levels were decreased in gcn-5KO strains and increased in hda-1KO strains at the promoter of frq gene. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; Student’s t test was used. (E) The hda-1KO strain exhibited near normal circadian period in the presence of 3-AT. hda-1KO strains were grown on the race tube medium containing the indicated concentrations of 3-AT in DD. (F) TSA treatment rescued the impaired circadian rhythm of cpc-3KO strain caused by 3-AT treatment. cpc-3KO strains were grown on the race tube medium containing 3 mM 3-AT and indicated concentrations of TSA in DD.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

RT-qPCR analysis dataset in Figure 6D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig6-data1-v2.zip

GCN-5 is the major histone acetyltransferase responsible for histone acetylation at the frq locus in response to amino acid starvation. On the other hand, the histone deacetylase HDA-1 was previously reported as a major histone deacetylase that can antagonize and compete with GCN-5 for recruitment to promoters to deacetylate H3 (Islam et al., 2011; Vogelauer et al., 2000). ChIP assays showed that H3ac levels were indeed significantly decreased in the gcn-5KO strain and were markedly increased in the hda-1KO strain at the frq promoter region (Figure 6D), indicating that HDA-1 is responsible for histone deacetylation at the frq locus. Race tube assays showed that in contrast to period lengthening in the WT strain by 3-AT (Figure 6A), the hda-1KO strain exhibited nearly normal circadian period even in the presence of high 3-AT concentrations (Figure 6E), suggesting that reduced histone deacetylation can partially rescue the circadian clock defects in response to amino acid starvation. To further confirm our conclusion, we treated the cpc-3KO strains with different concentrations of TSA and found that the arrhythmic circadian conidiation rhythm caused by 3-AT treatment could be partially rescued by TSA treatments (Figure 6F). Together, these results strongly suggest that the amino acid starvation induced clock defects in the GCN2 signaling pathway mutants are largely due to the decreased histone acetylation at the frq promoter, which prevents efficient WC-2 binding and disrupts the rhythmic frq transcription.

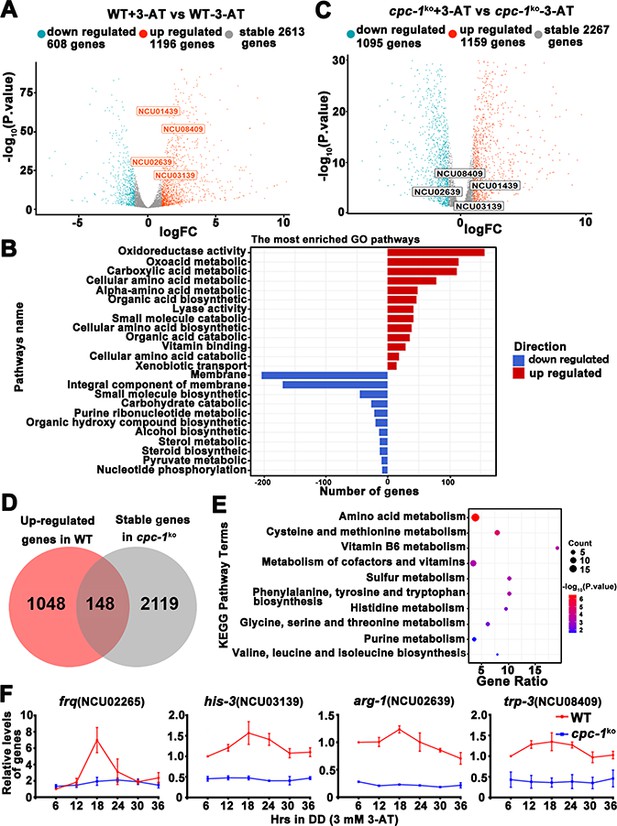

Rhythmic expression of CPC-1 activated metabolic genes under amino acid starvation

Circadian clock has been shown to control metabolic processes and rhythmic transcription of metabolic genes (Baek et al., 2019; Hurley et al., 2014; Hurley et al., 2018). To determine the role of the GCN2 pathway in controlling gene expression under amino acid starvation, we performed RNA-seq experiments to analyze the genome-wide mRNA levels in the WT and cpc-1KO strains in the presence of 3-AT (12 mM). As shown in Figure 7A, 22.1% of genes were found to be upregulated and 11.2% of genes were downregulated in the WT strain after 3-AT treatment compared with normal condition. Specifically, those genes involved in the regulation of oxidoreductase and amino acid metabolism were particularly enriched and were mostly upregulated during the amino acid starvation (Figure 7B). However, the differential expression of the 148 upregulated and 127 downregulated genes found in the WT strain was abolished in the cpc-1KO strain after 3-AT treatment, suggesting that these genes were regulated by CPC-1 under amino acid starvation (Figure 7D and Figure 7—figure supplement 1A, B). Similar to those in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Natarajan et al., 2001), genes of amino acid biosynthetic pathways, vitamin biosynthetic enzymes, peroxisomal components, and mitochondrial carrier proteins were also identified as CPC-1 targets. Among them, the genes involved in amino acid and vitamin metabolism were particularly enriched and were mostly upregulated during the amino acid starvation (Figure 7E). For example, amino acid synthesis genes his-3 (NCU03139), arg-1 (NCU02639), trp-3 (NCU08409), and ser-2 (NCU01439) were upregulated in the WT strain, but unchanged in the cpc-1KO strain under amino acid starvation (Figure 7A, C).

Circadian clock control of CPC-1-activated metabolic genes under amino acid starvation.

(A) Comparison of the transcript expression profiles of the WT strains with and without 12 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) treatment. (B) Gene functional enrichment analysis based on the mRNA levels changes for the up- and downregulated genes in the WT strains with and without 12 mM 3-AT treatment. (C) Comparison of the transcript expression profiles of the cpc-1KO strains with and without 12 mM 3-AT treatment. (D) Pie charts showing the overlaps of upregulated genes in the WT strain, but stable genes in the cpc-1KO strains after 12 mM 3-AT treatment. (E) Gene functional enrichment analysis based on the mRNA levels changes for the overlaps of upregulated genes in the WT strain, but stable genes in the cpc-1KO strains after 12 mM 3-AT treatment. (F) RT-qPCR analysis showing that amino acid synthetic genes his-3 (NCU03139) (n = 3; WT: p = 2.21E−05, cpc-1KO: p>0.05), arg-1 (NCU02639) (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0097, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05), and trp-3 (NCU08409) (n = 3; WT: p = 0.0009, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) were activated by CPC-1 and were rhythmic expressed with 3 mM 3-AT treatment. The primers used for RT-qPCR are shown in Key Resources Table.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Raw dataset of RNA-seq analysis in Figure 7A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig7-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 2

Raw dataset of RNA-seq analysis in Figure 7C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig7-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 3

RT-qPCR analysis dataset in Figure 7F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/85241/elife-85241-fig7-data3-v2.zip

To examine whether these CPC-1 activated genes were controlled by circadian clock, we re-analyzed and compared our identified CPC-1 target genes with previously published RNA-seq data of rhythm samples (Hurley et al., 2014; Hurley et al., 2018). As shown in Supplementary file 1, we summarized the rhythmic expression of 79 upregulated and 67 downregulated CPC-1 target genes based on the eJTK Cycle results of Hurley et al., 2018 (its Supplemental Datasets 1 and 2). We re-analyzed the rhythmicity of CPC-1-targeted genes (148 upregulated and 127 downregulated) using CircaSingle (Parsons et al., 2020), and added the p-values in Supplementary file 1. There were 146 rhythmic genes based on the eJTK Cycle, and 132 rhythmic genes based on the CircaSingle. As expected, there were 106 overlapping genes between these two sets of data, confirming the results using eJTK Cycle. Thus, we performed further analysis based on the data from eJTK Cycle. There were about 146/275 (53%) of the CPC-1 up- and downregulated genes under amino acid starvation exhibiting rhythmicity, indicating a highly significant enrichment of CPC-1 regulated genes as clock-controlled genes (p = 3.341905e−06, hypergeometric distribution test). Furthermore, we performed ChIP experiments to examine whether CPC-1 directly activates the expression of amino acid synthetic genes. As shown in Figure 7—figure supplement 1C, CPC-1 was found to be constitutively enriched at the promoters of his-3 (NCU03139), trp-3 (NCU08409), and ser-2 (NCU01439) genes (WT (0 mM 3-AT): p > 0.05, WT (3 mM 3-AT): p > 0.05, cpc-1KO (0 mM 3-AT): p > 0.05), and the enrichment was enhanced by 3-AT treatment. Because the CPC-1 binding was not rhythmic, we performed RT-qPCR experiments to re-analyze whether those genes were rhythmically transcribed in DD. Consistent with the published RNA-seq analysis results, we found that frq and the amino acid synthetic genes such as his-3 (NCU03139) (WT: p = 2.21E−05, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05), arg-1 (NCU02639) (WT: p = 0.0097, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05), and trp-3 (NCU08409) (WT: p = 0.0009, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) were rhythmically expressed in the WT but not cpc-1KO strain under amino acid starvation (Figure 7F). In addition, we also found that ser-2 (NCU01439) (WT: p = 2.25E−05, cpc-1KO: p > 0.05) exhibited rhythmic expression in the WT but not in the cpc-1KO strain under amino acid starvation (Figure 7—figure supplement 1D), even though it was not previously shown to be rhythmic in the published RNA-seq analysis study. These results suggest that many CPC-1-activated metabolic genes under amino acid starvation are regulated by circadian clock. Next, we performed RT-qPCR experiments to detect the mRNA levels of amino acid synthesis genes under normal condition (0 mM 3-AT), and found that arg-1 (NCU02639) (WT: p = 0.0353), trp-3 (NCU08409) (WT: p = 0.0436), and ser-2 (NCU01439) (WT: p = 0.0008) genes, but not the his-3 (NCU03139) (WT: p > 0.05) gene, were rhythmic in the WT strain in DD (Figure 7—figure supplement 1E). Together, these results suggest that the GCN2 signaling pathway functions to maintain the robust circadian clock and rhythmic expression of metabolic genes under amino acid starvation.

Discussion

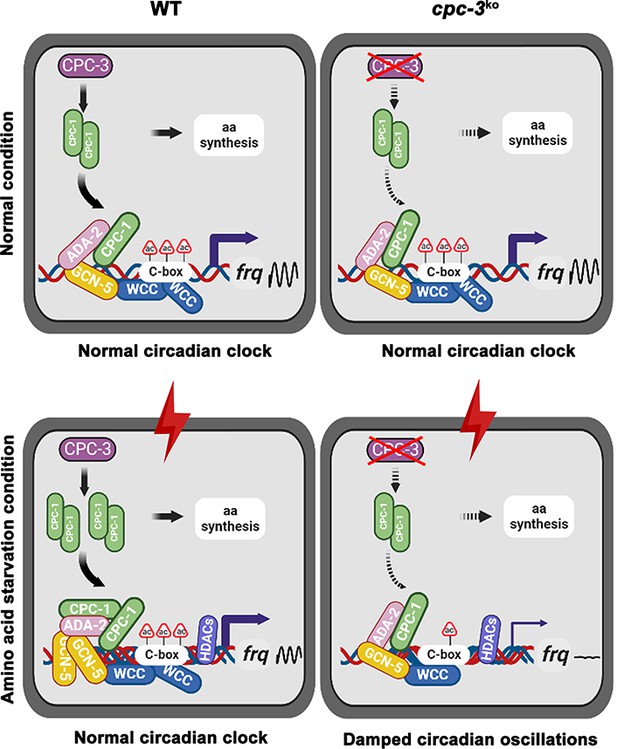

Circadian clock drives robust rhythmic gene expression and activities in different environmental and nutritional conditions. Here, we demonstrate that the nutrient-sensing GCN2 pathway plays an unexpected role in maintaining the Neurospora circadian clock in response to amino acid starvation stress. Under normal conditions, CPC-1 is expressed at its basal levels in the WT or cpc-3KO strain, which is required for rhythmic expression of frq gene by recruiting the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5 containing SAGA complex to the frq promoter. However, amino acid starvation resulted in compact chromatin structure (due to decreased H3ac) in the frq promoter in the WT strain (Figure 3B), likely due to activation of the histone deacetylases or inhibition of histone acetyltransferases. The circadian clock-controlled CPC-3 and CPC-1 signaling pathway (Karki et al., 2020) is activated by amino acid starvation, and the elevated CPC-1 protein efficiently recruits the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5 containing SAGA complex to the frq promoter to increase the histone acetylation levels and loosen the chromatin structure, which permits rhythmic WC-2 binding. Therefore, under amino acid starvation, the disruption of the CPC-3 and CPC-1 signaling pathway results in decreased histone acetylation levels, reduced WC-2 binding at the frq promoter and the loss of robust rhythmic frq transcription (Figure 8).

Model showing the role of CPC-3 and CPC-1 in maintaining the Neurospora circadian rhythm in response to amino acid starvation.

Under normal conditions, CPC-1 is expressed at its basal levels in the WT (Left) or cpc-3KO (Right) strain, which is required for rhythmic expression of frq gene by recruiting the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5 containing SAGA complex to the frq promoter. Under amino acid starvation conditions, the chromatin in the frq promoter of the WT strain is constitutively compacted (due to decreased H3ac), likely due to activation of histone deacetylases or inhibition of histone acetyltransferases. CPC-3 and CPC-1 signaling pathway was activated by amino acid starvation and the elevated CPC-1 protein would efficiently recruit the histone acetyltransferase GCN-5 containing SAGA complex to promote the histone acetylation levels, which permitted rhythmic WCC binding at the frq promoter (Left). Disruption of the CPC-3 and CPC-1 signaling pathway resulted in decreased histone acetylation levels of the frq gene promoter, reduced WCC binding and damped circadian oscillations in response to the amino acid starvation stress (Right).

Maintaining robust rhythmic gene expression and circadian activities in response to various environmental and nutritional stresses is important for the health or survival of different organisms. Circadian clock synchronizes metabolic processes and systemic metabolite levels, while nutrients and energy signals also feedback to circadian clocks to adapt their metabolic state (Bass, 2012; Hurley et al., 2014; Klemz et al., 2017; Reinke and Asher, 2019). Amino acid starvation is known to inhibit the global translation efficiency through activating GCN2-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation, which conserves energy and allows cells to reprogram gene expression to relieve stress damage. It was recently shown that circadian clock control of GCN2-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation was necessary for rhythmic translation initiation in Neurospora (Ding et al., 2021; Karki et al., 2020). However, it was previously unknown whether circadian clock would be affected by amino acid starvation stress. After activation of the GCN2-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation by amino acid starvation, a subset of transcripts containing overlapping upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in their 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) are efficiently translated, including the yeast transcription factor GCN4, the Neurospora CPC-1 and their mammalian ortholog ATF4, which activate the transcription of various amino acid biosynthetic genes (Hinnebusch, 1984; Paluh et al., 1988; Vattem and Wek, 2004). Our ChIP results showed that CPC-1 could rhythmically bind to the region close to C-box at the frq promoter to activate frq transcription (Figure 4A). WCC binding at the frq C-box region was slightly decreased under normal condition (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), and dramatically decreased under amino acid starvation in the cpc-1KO strain (Figure 2D), suggesting that CPC-1 cooperates with WCC to promote frq transcription in response to amino acid starvation. Although CPC-1 rhythmically bound at the frq promoter, ChIP experiments showed that CPC-1 binding at several selected amino acid biosynthetic genes did not appear to be rhythmic (Figure 7—figure supplement 1C). However, our RT-qPCR results (Figure 7F and Figure 7—figure supplement 1) and the previous RNA-seq data showed that many CPC-1-targeted metabolic genes were rhythmic expressed (Hurley et al., 2018). It is possible that the binding of CPC-1 to these promoters is still rhythmic but with low amplitudes. As a result, the limited sensitivity of our ChIP assays failed to detect these rhythms. Alternatively, the rhythmic transcription of these genes might be controlled by the rhythmic transcriptional activation activity of CPC-1 rather than its binding. In addition, the rhythmic binding of WCC or WCC-controlled transcription factors (Hurley et al., 2014) might also contribute to their rhythmic transcription.

Amino acid starvation was able to affect gene expression by regulating chromatin modifications. Mammalian transcription factor ATF2 was reported to promote the modification of the chromatin structure in response to amino acid starvation to enhance the transcription of numbers of amino acid-regulated genes (Bruhat et al., 2007). Amino acid starvation was also shown to induce reactivation of silenced transgenes and latent HIV-1 provirus by downregulation of histone deacetylase 4 in mammalian cells (Palmisano et al., 2012). Here, we found that amino acid starvation suppressed frq expression by decreasing the histone acetylation levels likely through activation of histone deacetylases or inhibition of histone acetyltransferases (Figure 3B). The activated GCN2 signaling pathway resulted in recruitment of the histone acetyltransferase SAGA complex to the frq promoter through its interaction with CPC-1 to re-establish a proper histone acetylation state to relieve the repression (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Although histone acetylation and deacetylation rhythms have been reported in mammalian cells (Papazyan et al., 2016; Takahashi, 2017), SAGA complex has also been reported to be involved in circadian regulation through interaction with the CLOCK complex in Drosophila (Mahesh et al., 2020), their function in circadian clock is unclear in Neurospora. Here we demonstrated the important role of GCN-5 in regulating the rhythmic histone acetylation and WC-2 binding at the frq promoter (Figure 5). Our study unveiled an unsuspected link between nutrient limitation and circadian clock function mediated by the GCN2 signaling pathway. These results provide key insights into the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of circadian gene expression during amino acid starvation.

The nutrient-sensing GCN2 signaling pathway is highly conserved in eukaryotic cells from yeast to mammals. In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae and the filamentous fungus N. crassa, the GCN2 kinase responds to nutrient deprivation, whereas it phosphorylates eIF2α and upregulates the master transcription factors GCN4 or CPC-1, respectively, which binds target DNA as a dimer to activate amino acid biosynthetic genes (Ebbole et al., 1991; Hinnebusch, 2005; Hope and Struhl, 1987). In mammalian cells, several GCN2-related kinases can phosphorylate eIF2α in response to various stress conditions, triggering the integrated stress response (Costa-Mattioli and Walter, 2020; Donnelly et al., 2013). Interestingly, different from the normal circadian period of cpc-3KO strain in Neurospora without amino acid starvation (Figure 1A, Figure 1—figure supplement 1 and Figure 1—figure supplement 2), it was reported that GCN2 modulated circadian period by phosphorylation of eIF2α in mammals under normal condition, but it was unknown whether GCN2 was involved in circadian regulation of metabolism under nutrient limitation (Pathak et al., 2019). Our results suggest that the GCN2 signaling pathway is required for maintaining circadian clock under amino acid starvation, which is important for robust rhythmic expression of metabolic genes (Figure 7). Because GCN2 signaling pathway is important for nutrient sensing, it may also be important for nutritional compensation (Kelliher et al., 2023) and plays a role in maintaining the robustness of rhythms in a range of nutritional conditions. Time-restricted feeding prevents obesity and metabolic syndrome through circadian-related mechanisms (Chaix et al., 2019), but how eating pattern affects circadian regulation is unclear. The conservation of the GCN2 signaling pathway and our results here suggest that GCN2 may play an important role in mediating circadian regulation of metabolism during nutrient limitation caused by feeding restrictions in mammals. Together, our studies suggest a conserved role of the GCN2 signaling pathway in maintaining the robustness of circadian clock under nutrient starvation in eukaryotes.

Materials and methods

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | 87-3 (ras-1bd, a) | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | 301-6 (ras-1bd, his-3-, A) | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;cpc-3KO | Fungal Genetics Stock Center | NCU01187 | |

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;cpc-1KO | Fungal Genetics Stock Center | NCU04050 | |

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;gcn-5KO | Fungal Genetics Stock Center | NCU10847 | |

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;ada-2KO | Fungal Genetics Stock Center | NCU04459 | |

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;hda-1KO | Fungal Genetics Stock Center | NCU01525 | |

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;cpc-1KO, cpc-1-Myc.CPC-1 | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | 301-6, cfp-Myc.CPC-1, cfp-Flag.ADA-2 | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | 301-6, cfp-Myc.GCN-5, cfp-Flag.ADA-2 | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | frq-luc | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;cpc-3KO, frq-luc | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;cpc-1KO, frq-luc | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | FRQ-LUC | Dr. Luis Larrondo’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;gcn-5KO, FRQ-LUC | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Strain, strain background (Neurospora crassa) | ras-1bd;ada-2KO, FRQ-LUC | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ||

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-Histone H2B | Abcam | Cat# ab1790 | 1:3000 |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-Histone H3ac | Millipore | Cat# 06-599 | 1:3000 |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc | TransGen | Cat# HT101 | 1:3000 |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag | Sigma | Cat# F1804 | 1:3000 |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-P-eIF2α | Abcam | Cat# ab32157 | 1:3000 |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-CPC-1 | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | 1:3000 | |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-FRQ | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | 1:3000 | |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-WC-1 | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | 1:4000 | |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-WC-2 | Dr.Yi Liu’s Laboratory | 1:8000 | |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | GCAGTGTCATTGACGACTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | CCTCCAACTCACGTTTCTTTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | his-3-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | CCTCGTTCGTCAAGCACATTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | his-3-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | CTCCTCAACCTTAGCCAACTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | trp-3-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | ACCTATATCCTTCAGAACCAATACG |

| Sequence-based reagent | trp-3-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | GCTCGGTATCCTTCCAGTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | ser-2-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | GCTGCTAACGGTGACTACTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | ser-2-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | GGTGAGGATGATGTTGTTGAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | arg-1-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | CCCATCATTGCCCGTGCCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | arg-1-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | TGACGACCCTGGAAGCGAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | β-tubulin-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | GCGTATCGGCGAGCAGTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | β-tubulin-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | RT-qPCR | CCTCACCAGTGTACCAATGCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq C-box-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | GTCAAGCTCGTACCCACATC |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq C-box-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | CCGAAAGTATCTTGAGCCTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq promoter-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | GTTGCCGTGACTCCCCCTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq promoter-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | CCGAAAGTATCTTGAGCCTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | his-3 ChIP-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | TTTTCATAAAGCCCGAGTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | his-3 ChIP-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | CAGGTATTGTGCTGTTCCCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | trp-3 ChIP-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | AATCGGGTGAGTCAAAGGCG |

| Sequence-based reagent | trp-3 ChIP-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | CGAGCAAGAGGGAGAGGTGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | ser-2 ChIP-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | GGGACAAAAGCAGTGATTCTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | ser-2 ChIP-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | ChIP-qPCR | CGATTTACATCCATCTGAGA |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq northern-F | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | Northern blot | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCTTCGTTGGATATCCATCATG |

| Sequence-based reagent | frq northern-R | Dr.Xiao Liu’s Laboratory | Northern blot | GAATTCTTGCAGGGAAGCCGG |

| Software, algorithm | ImageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ | ||

| Software, algorithm | LumiCycle | https://actimetrics.com/products/lumicycle/ | ||

| Software, algorithm | CircaCompare | https://github.com/RWParsons/circacompare/; Parsons et al., 2020 |

Strains, culture conditions, and race tube assay

Request a detailed protocolThe 87-3 (ras-1bd, a) and 301-6 (ras-1bd, his-3−, A) strain was used as the wild-type (WT) strain in this study. Knockout mutants were all generated based on the ras-1bd background (Belden et al., 2007). cpc-3KO (NCU01187), cpc-1KO (NCU04050), gcn-5KO (NCU10847), ada-2KO (NCU04459), and hda-1KO (NCU01525) strains were obtained from the Fungal Genetic Stock Center (FGSC) and were crossed with a ras-1bd strain to create the ras-1bd;cpc-3KO, ras-1bd;cpc-1KO, ras-1bd;gcn-5KO, ras-1bd;ada-2KO, and ras-1bd;hda-1KO strains (Colot et al., 2006). Constructs with the cpc-1 promoter driving expression of Myc.CPC-1 were introduced into the cpc-1KO strains at the his-3 (NCU03139) locus by homologous recombination. Constructs with the cfp promoter driving expression of Flag.ADA-2 were introduced into the 301-6, cfp-Myc.CPC-1 or 301-6, cfp-Myc.GCN-5 strains by random insertion with nourseothricin selection (He et al., 2020). Positive transformants were identified by western blot analyses, and homokaryon strains were isolated by microconidia purification with 5 µm filters.

Liquid cultures were grown in minimal media (1× Vogel’s, 2% glucose). For rhythmic experiments, Neurospora was cultured in petri dishes in liquid medium for 2 days. The Neurospora mats were cut into discs and transferred into medium-containing flasks and were harvested at the indicated time points.

The medium for race tube assay contained 1× Vogel’s salts, 0.1% glucose, 0.17% arginine, 50 ng/ml biotin, and 1.5% agar. After entrainment of 24 hr in the constant light condition, race tubes were transferred to constant darkness conditions and marked every 24 hr. The circadian period of the Neurospora strain could be calculated according to the ratio between the distance of marked conidia band positions and the distance of conidiation bands.

Luciferase reporter assay

Request a detailed protocolThe luciferase reporter assay was performed as reported previously (Gooch et al., 2008; Larrondo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). The luciferase reporter construct (frq-luc) containing the luciferase gene under the control of the frq promoter, was introduced into 301-6, cpc-3KO or cpc-1KO strains by transformation. The luciferase reporter construct (FRQ-LUC) containing a luciferase fused to the C terminus of the FRQ protein, was introduced into gcn-5KO or ada-2KO strains by crossing. Firefly luciferin (final concentration of 50 μM) was added to autoclaved FGS-Vogel’s medium containing 1× FGS (0.05% fructose, 0.05% glucose, 2% sorbose), 1× Vogel’s medium, 50 μg/l biotin, and 1.8% agar. Conidia suspension was placed on autoclaved FGS-Vogel’s medium and grown in constant light overnight. The cultures were then transferred to constant darkness, and luminescence was recorded in real time using a LumiCycle after 1 day in DD. The data were then normalized with LumiCycle analysis software by subtracting the baseline luciferase signal, which increases as cell grows.

Protein analysis

Request a detailed protocolProtein extraction, quantification, and western blot analyses were performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2017). Briefly, tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and suspended in ice-cold extraction buffer (50 mM Hydroxyethylpiperazine Ethane Sulfonic Acid HEPES (pH 7.4), 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) with protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml Pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml Leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride PMSF). After centrifugation, protein concentrations were measured using protein assay dye (Bio-Rad). For western blot analyses, equal amounts of total protein (40 μg) were loaded in each protein lane of 7.5% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) gels containing a ratio of 37.5:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, and western blot analyses using FRQ, WC-1, WC-2, P-eIF2α (Abcam, ab32157), and CPC-1 antibodies were performed. Western blot signals were detected by X-ray films and scanned for quantification.

To detect the phosphorylation levels of WC-1 and WC-2, PPase inhibitors (25 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7·10H2O, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid EDTA) were made fresh and added to the protein extraction buffer. Proteins were loaded in each protein lane of 7.5% SDS–PAGE gels containing a ratio of 149:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide.

RNA analysis

Request a detailed protocolRNA was extracted with Trizol and further purified with 2.5 M LiCl as described previously (Liu et al., 2017). For Northern blot analysis, equal amounts of total RNA (20 μg) were loaded onto agarose gels. After electrophoresis, the RNA was transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with [32P] UTP (PerkinElmer)-labeled RNA probes specific for frq. RNA probes were transcribed in vitro from PCR products by T7 RNA polymerase (Invitrogen, AM1314M) with the manufacturer’s protocol. The frq primers used for the template amplification are shown in Key Resources Table.

For RT-qPCR, the cultures of WT and cpc-1KO strains were collected at the indicated time points in constant darkness in liquid growth medium (1× Vogel’s, 2% glucose). RT-qPCR were performed as previously described (Cui et al., 2020). Each RNA sample (1 μg) was subjected to reverse transcription with HiScript II reverse transcriptase (Vazyme, R223), and then amplified by real-time PCR (Bio-Rad, CFX96). For RT-qPCR, primers target the coding genes of frq (NCU02265), his-3 (NCU03139), ser-2 (NCU01439), trp-3 (NCU08409), his-4 (NCU06974), arg-1 (NCU02639), and arg-10 (NCU08162) were designed, and the β-tubulin (NCU04054) was used as an internal control. The primers used for RT-qPCR are shown in Key Resources Table.

Generation of antiserum against CPC-1

Request a detailed protocolTwo CPC-1 peptides (SELDLLDFATFDGG and RDKPLPPIIVEDPS) were synthesized and used as the antigens to generate rabbit polyclonal antisera (ABclonal) as described previously (Cui et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2013).

Co-IP analysis

Request a detailed protocolImmunoprecipitation analyses were performed as previously described (Cao et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2001b). Briefly, Neurospora proteins were extracted as described above. For each immunoprecipitation reaction, 2 mg protein and 2 μl c-Myc (TransGen, HT101), 2 μl Flag (Sigma, F1804), or 2 μl WC-2 antibody (Cheng et al., 2001a) were used. After incubation with antibody for 3 hr, 40 μl GammaBind G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, 17061801) were added, and samples were incubated for 1 hr. Immunoprecipitated proteins were washed three times using extraction buffer before western blot analysis. IP experiments were performed using cultures harvested in constant light.

ChIP analysis

Request a detailed protocolChIP assays were performed as previously described (Cui et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2013) with 1 mg protein used for each immunoprecipitation reaction. The ChIP reaction was carried out with 2 μl WC-2 (Cheng et al., 2001a), CPC-1, H2B (Abcam, ab1790), or H3ac (Millipore, 06-599) antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by real-time qPCR. Occupancies were normalized by the ratio of ChIP to Input DNA. ChIP was performed using 2 μl c-Myc monoclonal antibody (TransGen, HT101) to examine occupancy of Myc.GCN-5. Occupancies of ChIP were normalized using IgG. The primers used for ChIP-qPCR are shown in Key Resources Table.

RNA-seq analysis

Request a detailed protocolThe WT and cpc-1KO strains were cultured with or without 12 mM 3-AT treatment in constant light. Total RNAs were extracted using Trizol reagents. Libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed using 150 bp paired-end Illumina sequencing (Annoroad Gene Technology, Beijing). After sequencing, the raw data were treated and mapped to the genome of Neurospora crassa and transformed into expression value. The gene expression levels were scored by fragments per kb per million (FPKM) method. The differences in gene expression between samples was compared by comparing FPKM values, and those with fold change more than 1 (False Discovery Rate FDR <0.1) were thought to be differentially expressed genes. The functional category enrichments, including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes KEGG terms, were analyzed. The KEGG pathway enrichment was evaluated based on hypergeometric distribution, and the R package ‘ggplot2’ version 3.3.6 was used to visualize the enrichment results.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolQuantification of western blot data were performed using Image J software. Error bars are standard deviations for ChIP assays from at least three independent technical experiments, and standard error of means for race tube assays from at least three independent biological experiments, unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. Statistical tests for the presence of rhythmicity and differences between two rhythms in parameters, including amplitude, phase, and mesor (the midline estimating statistic of rhythms) were analyzed using CircaSingle and CircaCompare (https://rwparsons.shinyapps.io/circacompare/) (Liu et al., 2021; Parsons et al., 2020). CircaCompare was used to compare the differences between two rhythmic datasets, and CircaSingle was used to re-analyze the rhythmic parameters of the RNA-seq results by eJTK Cycle. Amplitude refers to half of the difference between the peak and trough of a given response variable, phase refers to the time at which the response variable peaks, and mesor refers to the rhythm-adjusted mean level of a response variable around which a wave function oscillates. Statistical tests for the presence of rhythmicity and statistically significant differences between two groups of rhythmic parameters are indicated by p-values. A p-value <0.05 indicates the presence of rhythmicity, but a p-value >0.05 indicates the loss of rhythmicity. The results of the CircaSingle statistical tests are added in Supplementary file 1. The results of the CircaCompare statistical tests are summarized in Supplementary file 2.

Data and materials availability

Request a detailed protocolAll data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files. Our generated RNA sequencing data have been deposited in GEO under accession code GSE220169. RNA sequencing data from Hurley et al., 2014 were previously deposited to the NCBI SRA under accession number SRP046458 (Hurley et al., 2014). Materials are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files. Our generated RNA sequencing data have been deposited in GEO under accession code GSE220169.

-

NCBI Gene Expression OmnibusID GSE220169. The nutrient-sensing GCN2 signaling pathway is essential for circadian clock function by regulating histone acetylation under amino acid starvation.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA250475. Analysis of clock-regulated genes in Neurospora reveals widespread posttranscriptional control of metabolic potential.

References

-

Characterization of physical interactions of the putative transcriptional adaptor, ADA2, with acidic activation domains and TATA-binding proteinThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 270:19337–19344.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.33.19337

-

Circadian rhythms from multiple Oscillators: Lessons from diverse organismsNature Reviews. Genetics 6:544–556.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1633

-

Atf2 is required for amino acid-regulated transcription by orchestrating specific histone acetylationNucleic Acids Research 35:1312–1321.https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm038

-

Time-restricted eating to prevent and manage chronic metabolic diseasesAnnual Review of Nutrition 39:291–315.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-082018-124320

-

Differential regulation of phosphorylation, structure, and stability of circadian clock protein FRQ isoformsThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 299:104597.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104597

-

Nc2 complex is a key factor for the activation of catalase-3 transcription by regulating H2A.Z depositionNucleic Acids Research 48:8332–8348.https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa552

-

The eIF2α kinases: their structures and functionsCellular and Molecular Life Sciences 70:3493–3511.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-012-1252-6

-

The Neurospora crassa white COLLAR-1 dependent blue light response requires acetylation of histone H3 lysine 14 by NGF-1Molecular Biology of the Cell 17:4576–4583.https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e06-03-0232

-

The Neurospora crassa circadian clockAdvances in Genetics 58:25–66.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2660(06)58002-2

-

Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeastAnnual Review of Microbiology 59:407–450.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833

-

Understanding systems-level properties: Timely stories from the study of clocksNature Reviews. Genetics 12:407–416.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2972

-

Timing the day: What makes bacterial clocks tickNature Reviews. Microbiology 15:232–242.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.196

-

The histone methyltransferase MLL1 permits the oscillation of circadian gene expressionNature Structural & Molecular Biology 17:1414–1421.https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1961

-

Reciprocal regulation of carbon monoxide metabolism and the circadian clockNature Structural & Molecular Biology 24:15–22.https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3331

-

Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4P is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeastMolecular and Cellular Biology 21:4347–4368.https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.13.4347-4368.2001

-

Design principles of Phosphorylation-dependent Timekeeping in Eukaryotic circadian clocksCold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 10:a028357.https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a028357

-

Phase Resetting of the mammalian circadian clock by DNA damageCurrent Biology 18:286–291.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.047

-

Genetic and epigenomic mechanisms of mammalian circadian transcriptionNature Structural & Molecular Biology 23:1045–1052.https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3324

-

Methylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 4 by the Lysine Methyltransferase Set1 protein is needed for normal clock gene expressionThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 288:8380–8390.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.359935

-

Crosstalk between metabolism and circadian clocksNature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 20:227–241.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0096-9

-

Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clockNature Reviews. Genetics 18:164–179.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.150

-

Molecular regulation of circadian chromatinJournal of Molecular Biology 432:3466–3482.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2020.01.009

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170092)

- Xiao Liu

National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970079)

- Xiao Liu

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0911300)

- Xiao Liu

Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA28030402)

- Xiao Liu

Beijing Natural Science Foundation (5202020)

- Xiao Liu

CAS Interdisciplinary Innovation Team

- Xiao Liu

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200056)

- Xiao-Lan Liu

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0900500)

- Qun He

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170560)

- Qun He

National Institutes of Health (R35 GM118118)

- Yi Liu

Welch Foundation (I-1560)

- Yi Liu

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Luis Larrondo for providing the translational fused FRQ-LUC plasmid and strain, and Dr. Shaojie Li for providing Neurospora mutant strains. We thank Dr. Jay Dunlap and Dr. Jennifer Hurley for providing Neurospora RNA-seq information. We also thank Dr. Linqi Wang, Dr. Wenbing Yin, and members of our lab for assistance and discussions. This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170092, 31970079), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0911300), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA28030402), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (5202020), and CAS Interdisciplinary Innovation Team to Xiao Liu; National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200056) to Xiaolan Liu; National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0900500) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170560) to Qun He; National Institutes of Health (R35 GM118118) and the Welch Foundation (I-1560) to Yi Liu. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Copyright

© 2023, Liu, Yang et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,174

- views

-

- 271

- downloads

-

- 10

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 10

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.85241