Evolution: ANP32B, or not to be, that is the question for influenza virus

Every year, the influenza A virus causes flu epidemics around the world, and is also responsible for deadly pandemics like that of 1918. Like most viruses, it must hijack host cells to express its genes, replicate its genome, and produce new virions to infect more cells. Diverse populations of influenza A viruses circulate in birds, their natural reservoir, before emerging in humans and other mammals. As the bird viruses adapt to non-avian species, they face two major barriers: entering the cells of their new hosts, and being able to use their polymerase complex to replicate their genomes (Te Velthuis and Fodor, 2016; Long et al., 2019a). Entry into cells is controlled by receptors that the viruses must bind to, with different species expressing different variants of the receptors. However, the mechanism that blocks the activity of the viral polymerase in a new host, thus preventing the virus from replicating, is less well understood. Looking into the ways that influenza A virus infects new species, and how the hosts fight back, offers a glimpse into complex evolutionary processes in action.

The influenza polymerase is a complex formed of three proteins including one called PB2 (Te Velthuis and Fodor, 2016). Avian-style polymerases work well in bird cells, but poorly in humans. This species-specific restriction is due to the amino acid at position 627 in the PB2 subunit, which is a glutamate in birds and a lysine in humans (Almond, 1977; Subbarao et al., 1993). Changing this glutamate to lysine in an avian polymerase is sufficient to make it active in human cells, but the reasons for this were unclear.

The viral polymerase must recruit proteins from the host in order to transcribe and replicate the viral genome. In 2016, Wendy Barclay of Imperial College and colleagues finally identified ANP32A, the long-sought host co-factor that controls species specificity (Long et al., 2016). There are up to four members of the ANP32 family in vertebrates (A, B, C, and E), all of which have a whip-like shape (Figure 1). Rigorous biochemistry showed that the ANP32 proteins were key co-factors of the viral polymerase in human cells, with ANP32A and ANP32B having redundant roles (Sugiyama et al., 2015). However, just one member of the family in chickens – ANP32A – was able to stimulate avian polymerases; expressing chicken ANP32A in human cells rescued activity of the viral polymerases in an otherwise inhospitable species.

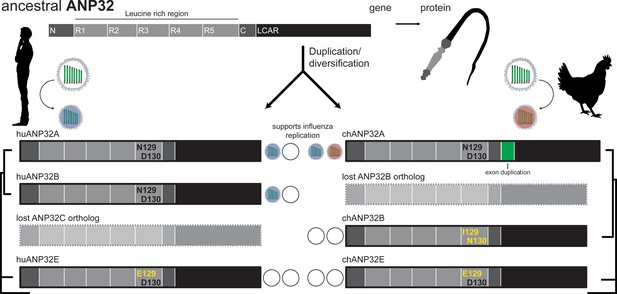

The evolution of ANP32 proteins.

ANP32 proteins have a whip-like shape, with an N-terminal region that is rich in leucine (light gray) and a low-complexity acidic region (LCAR; black). Different species bear different ANP32 proteins. The polymerase of the influenza A virus adapts to the ANP32 proteins that are present in different species so that it can replicate in the cells of a new host. Open circles indicate that an ANP32 protein is unable to support viral replication. In humans, ANP32A, 32B and 32E are present, and the influenza virus can use either ANP32A or ANP32B to support replication (blue circles). Human ANP32C is a pseudogene. In chicken, ANP32A, 32B and 32E are present, and the influenza virus relies exclusively on ANP32A (red circle). Open circles indicate that an ANP32 protein is unable to support viral replication. An exon duplication in ANP32A in chickens (green box) is required for the avian viral polymerase to work. Evolutionary analysis revealed that the avian gene previously identified as ANP32B in chickens is most closely related to ANP32C genes, as indicated by the trees on the outside of the diagram that show species-specific relationships between ANP32 genes. Long et al. and Zhang et al. identified the key residues that must be present in the ANP32 proteins for the viral polymerase to be active: asparagine (N) at site 129 and aspartate (D) at site 130. These amino acids are absent from human ANP32E and from chicken ANP32B and ANP32E.

However, it was not that human cells lacked ANP32A; rather, a duplication and insertion in chicken ANP32A added a unique exon to the gene. The insertion was common to almost all ANP32A proteins across birds and it was sufficient to confer activity to polymerases of avian origin. Subsequent studies began to dissect the activity of ANP32A and identified key features of this insert. In particular, they showed that, in birds, ANP32A is differentially spliced at the insert, creating ANP32A variants with different abilities to support polymerase function (Baker et al., 2018; Domingues and Hale, 2017). Thus, multiple lines of evidence converged on the importance of ANP32 proteins and their potential role in the evolution of influenza viruses. Now, in eLife, Barclay and colleagues at Imperial College, Edinburgh University, St George's in London and the Pirbright Institute – including Jason Long as first author – report, alongside a paper by Xiaojun Wang and colleagues in the Journal of Virology, that ANP32 proteins may have an even more intriguing evolutionary history (Long et al., 2019b; Zhang et al., 2019).

First, the experiments confirmed that ANP32A and ANP32B have a redundant role in helping the influenza virus to replicate in human cells. The double-knockout of ANP32A and ANP32B almost completely eliminated polymerase activity and virus replication, but simply deleting ANP32A had no effect (Long et al., 2019b; Zhang et al., 2019). HoweverIn contrast, removing only ANP32A in chickens was sufficient to stop the viral polymerase from working (Long et al., 2019b). Taken together, these results imply that both ANP32A and ANP32B support infection in humans, but only ANP32A performs this role in chickens, with ANP32B being unable to help the polymerase. Finally, neither human nor chicken ANP32Es played a major role during viral replication.

An in-depth investigation of ANP32B in chicken revealed that everything was not as it seemed. Evolutionary analyses showed that avian ANP32B forms a distinct group, and may actually be more closely related to ANP32C genes (and perhaps should be referred to as such) (Figure 1; Long et al., 2019b). Birds lost or never possessed the ANP32B version found in mammals, while the ANP32C gene that is closely related to avian ANP32B emerged in placental mammals as a non-functional pseudogene. Both Long et al. and Zhang et al. exploited their knockout cells to show that only two amino acid changes in chicken ANP32B eliminate its ability to support the viral polymerase (Figure 1). Avian ANP32A has asparagine and aspartate at residues 129 and 130, whereas avian ANP32B has isoleucine and asparagine at the same sites. These differences control the ability of the protein to interact with and promote the activity of the viral polymerase. Human ANP32A and ANP32B both have asparagine and aspartate at these sites, explaining why either protein supports the activity of the viral polymerase. These studies provide compelling evidence that subtle changes in ANP32 proteins can have large impacts on how viruses can exploit these proteins to replicate.

It is still unclear which evolutionary forces drove the duplication and subsequent diversification of the ANP32 loci, while also fixing the insertion in chicken ANP32A. How ANP32 proteins support the activity of the influenza polymerase also remains to be elucidated. In addition, it is likely that selective pressures on ANP32 proteins were not unique to birds. Mouse ANP32A, for example, only marginally supports polymerase activity (Zhang et al., 2019). In this species, ANP32A has asparagine and alanine at residues 129 and 130, a variation that the current studies would predict to be non-functional for the influenza virus. Instead, the mouse variant of ANP32B that has serine and aspartic acid at these sites is likely the dominant form which supports infection. It is curious that similar changes in ANP32A arise in pangolins, a species whose evolution is very distant from rodents and which has no obvious history with influenza virus. "For who would bear the whips of scorn and time", cries out Hamlet in the eponymous play. And indeed, the whip-like ANP32 proteins bear the telltale signs of mutation and diversification that suggest a long history of viruses exploiting these proteins.

References

-

Host and viral determinants of influenza A virus species specificityNature Reviews Microbiology 17:67–81.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0115-z

-

A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host rangeJournal of Virology 67:1761–1764.

-

Influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesisNature Reviews Microbiology 14:479–493.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.87

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2019, Baker and Mehle

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,470

- views

-

- 198

- downloads

-

- 14

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 14

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.48084