Mitochondrial protein import clogging as a mechanism of disease

Abstract

Mitochondrial biogenesis requires the import of >1,000 mitochondrial preproteins from the cytosol. Most studies on mitochondrial protein import are focused on the core import machinery. Whether and how the biophysical properties of substrate preproteins affect overall import efficiency is underexplored. Here, we show that protein traffic into mitochondria can be disrupted by amino acid substitutions in a single substrate preprotein. Pathogenic missense mutations in ADP/ATP translocase 1 (ANT1), and its yeast homolog ADP/ATP carrier 2 (Aac2), cause the protein to accumulate along the protein import pathway, thereby obstructing general protein translocation into mitochondria. This impairs mitochondrial respiration, cytosolic proteostasis, and cell viability independent of ANT1’s nucleotide transport activity. The mutations act synergistically, as double mutant Aac2/ANT1 causes severe clogging primarily at the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex. This confers extreme toxicity in yeast. In mice, expression of a super-clogger ANT1 variant led to neurodegeneration and an age-dependent dominant myopathy that phenocopy ANT1-induced human disease, suggesting clogging as a mechanism of disease. More broadly, this work implies the existence of uncharacterized amino acid requirements for mitochondrial carrier proteins to avoid clogging and subsequent disease.

Editor's evaluation

This manuscript describes important insight into the molecular mechanism by which destabilized mitochondrial proteins 'clog' import channels and contribute to the pathologic mitochondrial and cellular dysfunction implicated in human disease. The evidence supporting this conclusion is convincing, utilizing yeast, mammalian cell culture, and mouse models. This work, which defines an interesting mechanism of disease pathogenesis, will be of broad interest to researchers in the fields of mitochondrial biology, protein quality control and proteostasis.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.84330.sa0eLife digest

Inside our cells, compartments known as mitochondria generate the chemical energy required for life processes to unfold. Most of the proteins found within mitochondria are manufactured in another part of the cell (known as the cytosol) and then imported with the help of specialist machinery. For example, the TOM and TIM22 channels provide a route for the proteins to cross the two membrane barriers that separate the cytosol from the inside of a mitochondrion.

ANT1 is a protein that is found inside mitochondria in humans, where it acts as a transport system for the cell’s energy currency. Specific mutations in the gene encoding ANT1 have been linked to degenerative conditions that affect the muscles and the brain. However, it remains unclear how these mutations cause disease.

To address this question, Coyne et al. recreated some of the mutations in the gene encoding the yeast equivalent of ANT1 (known as Aac2). Experiments in yeast cells carrying these mutations showed that the Aac2 protein accumulated in the TOM and TIM22 channels, creating a ‘clog’ that prevented other essential proteins from reaching the mitochondria. As a result, the yeast cells died. Mutant forms of the human ANT1 protein also clogged up the TOM and TIM22 channels of human cells in a similar way.

Further experiments focused on mice genetically engineered to produce a “super-clogger” version of the mouse equivalent of ANT1. The animals soon developed muscle and neurological conditions similar to those observed in human diseases associated with ANT1.

The findings of Coyne et al. suggest that certain genetic mutations in the gene encoding the ANT1 protein cause disease by blocking the transport of other proteins to the mitochondria, rather than by directly affecting ANT1’s nucleotide trnsport role in the cell. This redefines our understanding of diseases associated with mitochondrial proteins, potentially altering how treatments for these conditions are designed.

Introduction

Mitochondria are essential organelles responsible for a wide range of cellular functions. To carry out these functions, they are equipped with a proteome of 1,000–1,500 proteins (Sickmann et al., 2003; Pagliarini et al., 2008; Morgenstern et al., 2017; Morgenstern et al., 2021). The vast majority of these proteins are encoded by the nuclear genome, synthesized in the cytosol, and sorted into one of the four mitochondrial sub-compartments, namely the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), intermembrane space (IMS), inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), and the matrix (Neupert and Herrmann, 2007; Endo and Yamano, 2009; Chacinska et al., 2009; Wiedemann and Pfanner, 2017). The entry gate by which >90% of mitochondrial proteins enter mitochondria is the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex. Therefore, proper function of the TOM complex is paramount for mitochondrial function and cell viability.

After passage through the TOM complex, specialized protein translocases transport preproteins into the mitochondrial sub-compartments (Neupert and Herrmann, 2007; Endo and Yamano, 2009; Chacinska et al., 2009; Wiedemann and Pfanner, 2017; de Marcos-Lousa et al., 2006). The import of mitochondrial carrier proteins to the protein-dense IMM is particularly challenging. Molecular chaperones like Hsp70 and Hsp90 target these highly hydrophobic proteins through the cytosol to the Tom70 receptor, which is associated with the TOM complex on the mitochondrial surface (Young et al., 2003; Bhangoo et al., 2007). After transport through the channel-forming Tom40 subunit of the TOM complex, the heterohexameric small TIM chaperones (i.e. the Tim9-Tim10 complex) transport the preprotein to the carrier translocase of the inner membrane (TIM22 complex) (Koehler et al., 1998; Sirrenberg et al., 1998; Wiedemann et al., 2001; Truscott et al., 2002; Webb et al., 2006; Weinhäupl et al., 2018; Ellenrieder et al., 2019). The carrier translocase is a multisubunit complex that inserts carrier proteins into the IMM in a membrane potential (Δψ)-dependent manner (Sirrenberg et al., 1996; Kerscher et al., 1997; Kovermann et al., 2002; Rehling et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2021). The central subunit Tim22 integrates carrier proteins into the IMM (Rehling et al., 2003; Peixoto et al., 2007). It associates with different partner proteins in yeast and human mitochondria. In yeast, Tim18 and Sdh3 are required for assembly and stability of the carrier translocase, whereas Tim54 tethers the small TIM chaperones (Tim9-Tim10-Tim12 complex) to the translocase (Wagner et al., 2008; Gebert et al., 2011). In human cells, TIM22 associates with the acylglycerol kinase (AGK) and TIM29, which are both required for full import capacity (Kang et al., 2016; Callegari et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2017; Vukotic et al., 2017). Human TIM22 also associates with the TIM9-TIM10 complex (Qi et al., 2021).

Several diseases are associated with mutations directly affecting the protein import machinery of the carrier pathway. For example, mutations in TIMM8A have been found in patients suffering Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome/deafness dystonia syndrome (Koehler et al., 1999). Mutations in TOMM70 and TIMM22 have been linked to a devastating neurological syndrome and a mitochondrial myopathy, respectively (Pacheu-Grau et al., 2018; Dutta et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). Mutations in another TIM22 complex subunit, AGK, has been associated with the Senger’s syndrome marked by cataracts, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, and exercise intolerance (Kang et al., 2017; Vukotic et al., 2017; Mayr et al., 2012). Clearly, defective protein import is linked to neurological and musculoskeletal diseases. However, whether protein import defects contribute to diseases not directly related to mutations in the core protein import machinery is unclear.

Here, we show that pathogenic missense mutations in a mitochondrial carrier protein, ADP/ATP translocase 1 (ANT1) or ADP/ATP carrier 2 (Aac2) in yeast, cause arrest of the protein at the translocases during import into mitochondria. This effectively ‘clogs’ the protein import pathway to obstruct general protein import and is associated with muscle and neurological disease in mice. Our findings demonstrate that global protein import is vulnerable to missense mutations in mitochondrial preproteins, and also provide strong evidence that protein import clogging contributes to neurological and muscular syndromes caused by dominant mutations in Ant1 (Kaukonen et al., 2000; Siciliano et al., 2003; Simoncini et al., 2017).

Results

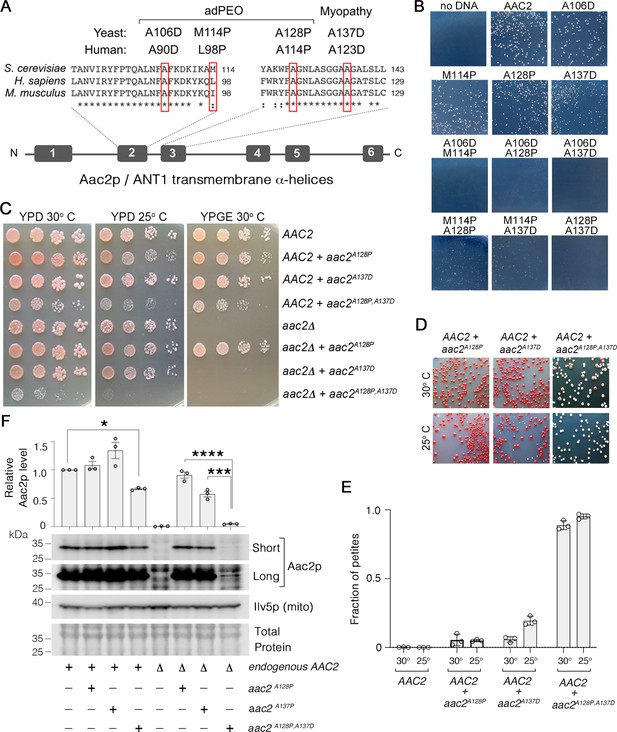

Super-toxic Aac2p mutants dominantly kill cells

We previously showed that four pathogenic ANT1 variants modeled in the yeast Aac2p (Figure 1A) share numerous dominant phenotypes including cold sensitivity, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) instability, a propensity to misfold inside mitochondria, and hypersensitivity to low Δψ conditions (Wang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2015; Coyne and Chen, 2019). We reasoned that if the mutant proteins share a common mechanism of toxicity that drives these phenotypes, then combining mutations into a single protein may enhance toxicity. To test this, we transformed the wild-type M2915-6A yeast strain with centromeric plasmids expressing wild-type, single and double mutant aac2 alleles, and selected for Ura+ transformants on glucose medium. We found that transformants expressing aac2M114P,A128P and aac2M114P,A137D formed smaller colonies on the selective medium at 25°C relative to wild-type AAC2 and single mutant alleles (Figure 1B). Strikingly, transformants expressing aac2A106D,M114P, aac2A106D,A128P, aac2A106D,A137D, and aac2A128P,A137D were unable to form visible colonies at 25°C. Growth of transformants expressing some of the double mutants were improved at 30°C (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). These data suggest that combining missense mutations into a single Aac2 protein increases toxicity, even when expressed from a centromeric vector.

Super-toxic Aac2p mutants dominantly kill cells.

(A) Schematic showing the location of pathogenic mutations in transmembrane α-helices 2 and 3 of the ADP/ATP translocator in human (ANT1) compared with mouse (Ant1) and yeast (Aac2p). adPEO, autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia. (B) Expression of double mutant aac2 alleles is highly toxic. The yeast M2915-6A strain was transformed with the centromeric vector pRS416 (URA3) expressing wild-type or mutant aac2 alleles and transformants were grown on selective glucose medium lacking uracil at 25°C for 3 days. (C) Growth of yeast cells after serial dilution, showing dominant toxicity of aac2A128P,A137D that is integrated into the genome in the W303-1B strain background. YPD, yeast peptone dextrose medium; YPGE, yeast peptone glycerol ethanol medium. (D) The aac2A128P,A137D allele dominantly increases the frequency of ‘petite’ colonies, which are white. This indicates mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) destabilization. (E) ‘Petite’ frequencies of yeast strains expressing the mutant alleles of aac2. The strains were first grown in YPD medium for 24 hr before being plated on YPD medium for scoring ‘petite’ colonies. (F) Immunoblot analysis showing extremely low levels of Aac2pA128P,A137D (lower panels) Ilv5p was used as a loading control for mitochondrial protein. Total protein determined with total protein stain (LI-COR). Short, short exposure; Long, long exposure. Upper panel, quantitation from three independent experiments. Aac2p values were normalized by Ilv5p to control for mitochondrial content, and data were represented as relative to wild-type; * indicates p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 from one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Data represented as mean ± SEM.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Uncropped Western blots from Figure 1F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig1-data1-v2.zip

We integrated a single copy of aac2A128P,A137D into the genome of both AAC2 and aac2Δ strains in the W303-1B background. We chose this strain background for two reasons: first, it is more tolerant of mutant aac2 expression (Wang et al., 2008); and second, mutant aac2 expression is not ρ0-lethal in this background (like it is in M2915-6A and BY4741), meaning that cells expressing mutant aac2 alleles can survive the loss of mtDNA. This allows us to score mtDNA instability via quantitation of smaller white colonies (‘petites’) that form when mtDNA is mutated or depleted (Chen and Clark-Walker, 2000). We found that growth of cells co-expressing aac2A128P,A137D and AAC2 is reduced on glucose medium (Figure 1C), and they form petites at a much higher frequency compared with those expressing the aac2A128P and aac2A137D single mutant alleles (Figure 1D–E). In the aac2Δ background, neither Aac2pA137D nor Aac2pA128P,A137D supported respiratory growth (Figure 1C), consistent with the A123D/A137D mutation eliminating nucleotide transport activity (Palmieri et al., 2005). Cells expressing only aac2A128P,A137D were barely viable, and cell growth was completely inhibited at 25°C even on glucose medium (Figure 1C). This is in sharp contrast to the AAC2-null strain, which strongly supports a dominant effect of aac2A128P,A137D on cell viability.

Interestingly, we found that Aac2pA128P,A137D accumulates to just 4.7% of wild-type Aac2 levels (Figure 1F). We did not observe any accumulation of aggregated Aac2pA128P,A137D (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B–C), indicating that Aac2pA128P,A137D degradation (see below), rather than aggregation, is the likely explanation for low protein recovery. Taken together, the data indicate that aac2A128P,A137D imparts potent toxicity through a mechanism that is independent of nucleotide transport.

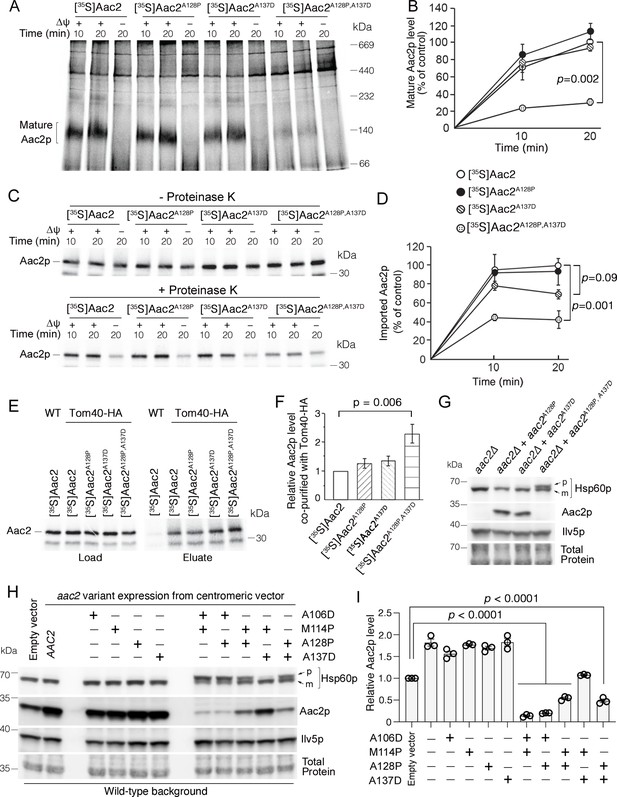

Super-toxic Aac2 proteins clog the TOM complex

We hypothesized that the highly toxic double mutant Aac2p is arrested during mitochondrial protein import thereby clogging protein import. To test this, we imported 35S-labeled Aac2p variants into wild-type mitochondria and analyzed the import reaction by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) followed by autoradiography (Figure 2A; Ellenrieder et al., 2019; Ryan et al., 1999). We did not observe a significant reduction in the amount of IMM-inserted ‘mature’ Aac2pA128P or Aac2pA137D compared with wild-type Aac2p, suggesting no obvious defect for importing into wild-type mitochondria that are fully energized in vitro. In contrast, integration of the double mutant Aac2pA128P,A137D into the IMM was reduced by >70% (Figure 2A–B). To determine whether the mutant preprotein can enter mitochondria, we treated the import reaction with proteinase K to digest non-imported preproteins. We found that a significant portion of mutant Aac2p, particularly Aac2pA128P,A137D, is sensitive to proteinase K digestion (Figure 2C–D). These data suggest that either the Aac2pA128P,A137D preprotein is not transported to the TOM complex, or it fails to fully traverse the TOM complex. To decipher between these possibilities, we imported Aac2p variants into mitochondria containing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Tom40 for affinity purification of the TOM complex. Indeed, Aac2pA128P,A137D had increased association with Tom40-HA compared with wild-type (Figure 2E–F). These observations suggest that a significant fraction of Aac2pA128P,A137D is arrested at the TOM complex during import into fully energized wild-type mitochondria.

Super-toxic ADP/ATP carrier 2 (Aac2) proteins clog the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex.

(A) In vitro protein import assay. 35S-labeled Aac2p and mutant variants were imported into wild-type mitochondria for 10 or 20 min and analyzed by blue native electrophoresis and autoradiography. (B) Quantitation from three independent experiments depicted in (A). p-Value from two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (C) 35S-labeled Aac2p and mutant variants were imported into wild-type mitochondria without (upper) or with (lower panel) subsequent proteinase K treatment to degrade non-imported preproteins. Reaction analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (D) Quantitation from three independent experiments depicted in (C). p-Values were calculated as in (B). (E) Preferential association of mutant Aac2p with Tom40-HA. 35S-labeled Aac2p and mutant variants were imported into Tom40-HA mitochondria, followed by anti-HA immunoprecipitation and analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (F) Quantitation from three independent experiments depicted in (E). p-Value was calculated with a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (G) Immunoblot analysis showing accumulation of the un-cleaved precursor of Hsp60p (p) in cells expressing chromosomally integrated aac2A128P,A137D. Cells were grown in YPD at 30°C. m, mature (i.e. cleaved). (H) Immunoblot analysis showing accumulation of un-cleaved Hsp60p precursor (p) in cells expressing aac2 alleles from a centromeric vector. Cells were grown in yeast nitrogen-based dextrose media with supplemented casamino acids, lacking uracil at 25°C. (I) Quantitation from three replicates of (H). Aac2p values normalized by the mitochondrial protein Ilv5p, and then normalized to vector-transformed samples. p-Values were calculated as in (F). Data represented as mean ± SEM.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Uncropped autoradiographs (Figure 2A,C,E) and Western blots (Figure 2G,H).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig2-data1-v2.zip

Next we wondered whether Aac2pA128P,A137D clogs the TOM complex in vivo. If it does, we would expect the accumulation of unprocessed mitochondrial preproteins that travel through the TOM complex, which would include the vast majority of intramitochondrial proteins including both TIM22 and TIM23 substrates. Indeed, precursor of the mitochondrial matrix protein Hsp60p was readily detectable in cells expressing Aac2pA128P,A137D despite extremely low levels of the mutant protein (Figure 2G). We also acutely expressed aac2 from galactose-inducible GAL10 promoter to limit possible indirect effects on protein import efficiency. As expected, expression of mutant aac2 from the GAL10- promoter was highly toxic (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). Importantly, the timing of Hsp60p precursor accumulation (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B) was coupled with the induction of the mutant Aac2p (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). The data suggest that the mutant Aac2p directly affects the import of other mitochondrial proteins in vivo.

We extended our analysis to include additional single and double mutant aac2 alleles (see Figure 1A). In transformants expressing double mutant aac2 alleles from a centromeric vector, the level of un-cleaved Hsp60p correlated with toxicity (Figure 2H, see also Figure 1B and Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). Moreover, total Aac2p levels were reduced by all double mutant Aac2p variants except the least toxic Aac2pM114P,A137D (Figure 2H–I). This suggests impaired biogenesis of endogenous wild-type Aac2p. The extent of endogenous Aac2 reduction also correlated with cell toxicity. These data further support the idea that protein import clogging underlies the super-toxicity of Aac2p double mutant.

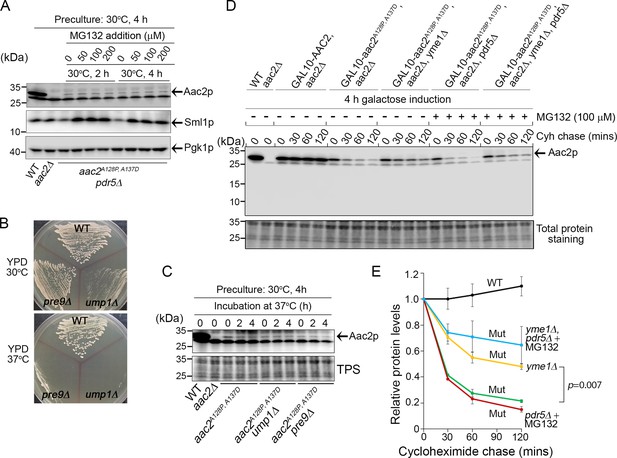

Yme1p, but not the proteasome, contributes substantially to Aac2pA128P,A137D degradation

We hypothesized that the proteasome should degrade Aac2A128P,A137D as it clogs at the TOM complex. To test this, we first generated strains lacking the drug efflux pump Pdr5p, which allows accumulation of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in yeast cells. Proteasome inhibition by MG132 was confirmed by the accumulation of Sml1p, a labile proteasome substrate (Figure 3A; Andreson et al., 2010). The experiment was performed in aac2Δ background to facilitate Aac2pA128P,A137D detection. Interestingly, we found that MG132 failed to increase the steady-state level of Aac2pA128P,A137D (Figure 3A). As an orthogonal approach, we tested whether proteasome dysfunction induced by two temperature-sensitive mutants, ump1Δ and pre9Δ, could increase Aac2pA128P,A137D levels, and observed no effect (Figure 3B–C). Cyclohexamide chase following a galactose-induced Aac2pA128P,A137D synthesis confirmed that the mutant protein is unstable compared with the wild-type Aac2p (Figure 3D–E). Consistently, MG132 failed to stabilize acutely induced Aac2pA128P,A137D. These data suggest that little, if any, Aac2pA128P,A137D is degraded by the proteasome.

Degradation of Aac2pA128P, A137D by Yme1p.

(A) Effect of MG132 on the steady-state level of Aac2A128P, A137D in a strain disrupted of PDR5 and AAC2. Cells were first grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 hr before MG132 was added at the indicated concentrations. Cells were cultured for another 2 or 4 hr before being harvested for western blot analysis. Sml1 was used as a control for proteasome inhibition. (B) Temperature-sensitive phenotype of ump1Δ and pre9Δ cells. Cells were grown at the indicated temperatures for 2 days before being photographed. (C) Western blot analysis showing that ump1Δ and pre9Δ do not affect the steady-state level of Aac2pA128P, A137D. Cells were grown in YPD medium for 2 and 4 hr at the restrictive temperature (37°C) before being analyzed for Aac2pA128P, A137D levels. TPS, total protein staining. (D) Western blot showing the stability of Aac2pA128P, A137D after cycloheximide (Cyh) chase in cells disrupted of YME1 or treated with MG132, following GAL10-induced synthesis of Aac2pA128P, A137D in galactose medium at 30°C for 4 hr. (E) Quantification of data for the turnover rate of Aac2pA128P, A137D (Mut) and its wild-type control (WT) depicted in (D). Aac2 levels were first normalized by total protein stain and then plotted as values relative to time zero. Depicted are mean values ± SEM from three independent experiments. p-Value was calculated with a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to compare genotypes at time = 120 min.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Uncropped Western blots from Figure 3A,C,D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig3-data1-v2.zip

Next we tested whether an intramitochondrial proteolytic system is responsible for Aac2pA128P,A137D degradation. One likely candidate is Yme1p, which is an IMS-facing AAA protease whose genetic deletion is synthetically lethal with single mutant aac2 variants (Wang et al., 2008). Indeed, we found that Aac2pA128P,A137D is significantly but not fully stabilized in cells disrupted of YME1 (Figure 3D–E). Inhibition of proteasomal function with MG132 does not significantly stabilize Aac2pA128P,A137D in yme1Δ cells. These data strongly suggest that Yme1p plays an important role in the degradation of Aac2pA128P,A137D, possibly serving as a quality control mechanism for degrading stalled import substrates in the vicinity of TIM22 and/or the TOM complex (Wu et al., 2018).

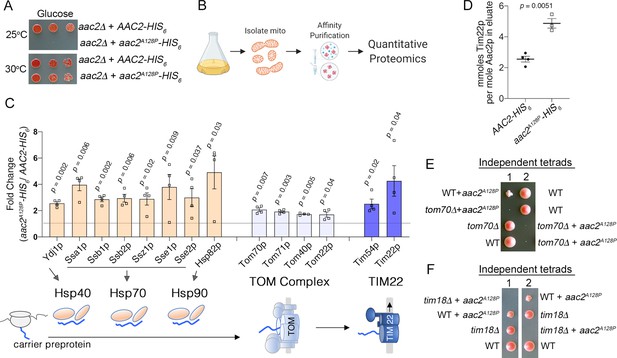

Aac2pA128P accumulates along the carrier import pathway and induces protein import stress

The single mutant Aac2p variants did not show significantly reduced import in vitro and only a mild accumulation at the TOM complex (Figure 2A–B; E-F). However, acute overexpression of the single mutant Aac2pA128P led to accumulation of the precursor form of Hsp60p, consistent with clogging of the translocation apparatus (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). To explore an arrest of Aac2pA128P at protein translocases, we performed affinity purification Aac2p-HIS6 and Aac2pA128P-HIS6 followed by a quantitative proteomic comparison of the co-purified proteins (Figure 4A–B; Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–C). Numerous proteins preferentially co-purify with Aac2pA128P-HIS6 over Aac2p-HIS6 (Figure 4—source data 1), which were enriched for chaperones involved in targeting of mitochondrial preproteins through the cytosol (Figure 4C; Figure 4—figure supplement 1D–F). Aac2pA128P also has increased association with the TOM complex, as well as the translocase of the inner membrane (TIM22) complex that is responsible for the Δψ-dependent insertion of carrier proteins into the IMM (Figure 4C). The association with Tim22p was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 4—figure supplement 1G–H). Expectedly, there is no increased association of Aac2pA128P with Tim23p, which is known to associate with wild-type Aac2p and is not involved in its import (Figure 4—figure supplement 1I; Dienhart and Stuart, 2008). Repeat affinity purification, except with double the ionic strength in the binding buffer, reproduced these data (Figure 4—figure supplement 2A–E, Figure 4—figure supplement 2—source data 1).

Aac2pA128P accumulates along the carrier import pathway and induces protein import stress.

(A) Growth of cells after serial dilution showing that aac2A128P-HIS6 is toxic at 25°C on glucose medium in an M2915-6A-derived strain. (B) Schematic of our approach to identify aberrant protein-protein interactions of Aac2pA128P-HIS6. (C) Co-purified proteins significantly enriched in Aac2pA128P-HIS6 eluate compared with Aac2p-HIS6. See Materials and methods for details on abundance value calculation. FDR-corrected p-values depicted are from multiple t test analysis. Lower panel is a schematic of the mitochondrial carrier protein import pathway. (D) Absolute quantities of Aac2p and Tim22p in Aac2p-HIS6 and Aac2pA128P-HIS6 eluates, as determined by parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) mass spectrometry. p-Value was calculated with Student’s t test. (E–F) Tetrad analysis demonstrating lethality of aac2A128P expression with genetic defects in carrier protein import in the M2915-6A strain background. Cell were grown on YPD at 30°C. Data depicted as mean ± SEM.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Proteins that preferentially interact with Aac2pA128P-HIS6, compare with Aac2-HIS6 in low-salt conditions.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig4-data1-v2.xlsx

To quantitate the increased association of Aac2pA128P to Tim22p relative to the wild-type Aac2p, we performed targeted quantitative proteomics (Figure 4—figure supplement 2F). We found that ~5 mmoles of Tim22p are pulled down per mole of Aac2pA128P-HIS6 (Figure 4D). If 5 mmoles per mole of Aac2pA128P molecules are bound to Tim22p in vivo, this could theoretically occupy ~85% of Tim22p channels, as Aac2p is present at ~188,000 molecules per cell and Tim22p at just 1100 (Morgenstern et al., 2017). Taken together, the data suggest that Aac2pA128P is stalled at both the TOM and TIM22 complexes during import.

Genetic and transcriptional analyses provided additional support for a clogging activity associated with Aac2pA128P. First, we observed that aac2A128P-expressing cells are sensitive to genetic perturbation to the carrier import pathway. TOM70 and TIM18 are two non-essential genes directly involved in the import of mitochondrial carrier proteins such as Aac2, serving as an import receptor at the TOM complex and a component of the TIM22 complex, respectively (Young et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2008). We found that meiotic segregants combining aac2A128P expression with tom70Δ or tim18Δ form barely visible microcolonies at 30°C on glucose medium (Figure 4E–F). It was recently proposed that Tom70p’s primary function is to recruit chaperones to the mitochondrial surface to prevent proteotoxicity in this protein-dense region (Backes et al., 2021). Thus, deletion of TOM70 may affect aac2A128P cells by two mechanisms: first, by further reducing carrier protein import and subsequently by impairing cytosolic proteostasis in the context of mitochondrial preprotein overaccumulation in the cytosol (Wang and Chen, 2015).

Next, we wondered whether the cellular response to acute Aac2pA128P expression could be indicative of protein import stress. To test this, we surveyed expression levels of a panel of genes known to be upregulated by clogging the TOM complex. These experiments were performed in the BY4742 strain background, in which expression of aac2A128P is incompatible with mtDNA loss (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A), thus minimizing any transcriptional effects secondary to mtDNA loss. We found that CIS1 transcript levels are acutely increased upon expression of aac2A128P, but not of AAC2, from a GAL10 promoter (Figure 4—figure supplement 3B). CIS1 upregulation is the hallmark of the mitochondrial compromised protein import response (mitoCPR) (Weidberg and Amon, 2018). We also found that RPN4, HSP82, SSA3, and SSA4 are transiently upregulated (Figure 4—figure supplement 3C–F), consistent with previously published gene activation patterns induced by a synthetic mitochondrial protein import clogger (Boos et al., 2019). Thus, transcriptional responses further suggest that Aac2pA128P clogs the protein import machinery.

Accumulating evidence suggests a functional crosstalk between the mitochondrial protein translocases and phospholipid biosynthesis/trafficking pathways (Hoffmann and Becker, 2022; Garg et al., 2022). Interestingly, we found that aac2A128P,A137D expression renders cells hypersensitive to defects in phospholipid homeostasis. We expressed aac2A128P,A137D in cells impaired in production of cardiolipin (CL) (pel1Δ) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (psd1Δ). Expression of aac2A128P,A137D strongly inhibited the growth of cells in these genetic backgrounds (Figure 4—figure supplement 3G–H). The data are consistent with previous observations that CL and PE facilitate mitochondrial protein import (Becker et al., 2013; Gebert et al., 2009). Alternatively, mitochondrial protein import clogging may affect phospholipid homoeostasis, which synergizes with pel1Δ and psd1Δ to cause cell lethality.

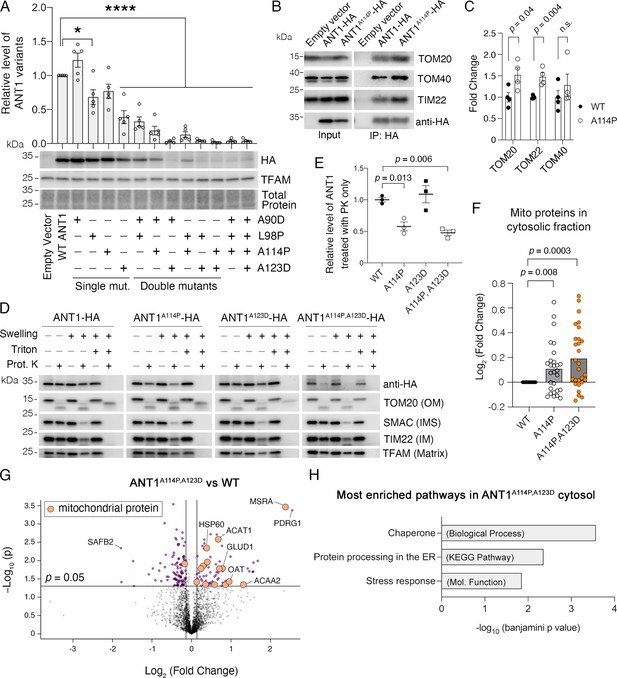

ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D clog mitochondrial protein import in human cells

We introduced equivalent mutations in human SLC25A4 (encoding the ANT1) with a C-terminal HA-tag, and transiently expressed the mutant proteins in HeLa cells (see Figure 1A). Like in yeast, combining missense mutations in Ant1 dramatically reduced steady-state protein levels, suggesting impaired ANT1 biogenesis (Figure 5A). Most strikingly, the level of ANT1A114P,A123D, equivalent to the yeast Aac2pA128P,A137D, is only 2.2% of the wild-type. Three lines of evidence suggest that ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D obstruct protein import into mitochondria. First, immunoprecipitation of ANT1A114P-HA demonstrated that the mutant protein has increased interactions with components of both TOM and TIM22 complexes (Figure 5B–C), as observed with its yeast ortholog Aac2pA128P. A meaningful immunoprecipitation of Aac2pA128P,A137D-HA was precluded by the extremely low-level accumulation of the mutant protein. Second, protease protection assay demonstrated that 42% and 52% of total ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D proteins are exposed on the OMM, whereas the wild-type ANT1 is protected from proteinase K digestion (Figure 5D–E). This is consistent with in vitro import studies of the Aac2p variants in yeast mitochondria (Figure 2A–F). Third, proteomics demonstrated that mitochondrial proteins accumulate in the cytosol of SLC25A4 p.A114P and SLC25A4 p.A114P,A123D -transfected cells, compared with wild-type Ant1-transfected cells (Figure 5F). Moreover, mitochondrial matrix proteins were significantly enriched in the cytosol of ANT1A114P,A123D versus ANT1-expressing cells (FDR<3×10–6) (Figure 5G; Figure 5—source data 1), corroborating that the double mutant Aac2p impairs global protein import. We therefore conclude that ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D clog protein import in human cells, with ANT1A114P,A123D having enhanced clogging activity despite low protein levels.

ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D clog mitochondrial protein import in human cells.

(A) Combining pathogenic mutations in ADP/ATP translocase 1 (ANT1) strongly reduces protein levels, as indicated by immunoblot analysis of ANT1-hemagglutinin (HA) levels 24 hr after transfecting HeLa cells. ANT1 variant levels were normalized by TFAM, then plotted as relative to wild-type level. * indicates p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 from one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (B) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of ANT1-HA and ANT1A114P-HA from transiently transfected HeLa cells followed by immunoblot analysis, showing that ANT1A114P has increased interaction with the protein import machinery like its yeast ortholog Aac2pA128P. (C) Quantitation from four independent IP, one of which is depicted in (B). p-Values were calculated with a Student’s t test. (D) Immunoblot analysis following protease protection assay showing that ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D are sensitive to proteinase K (PK) in isolated mitochondria. Swelling in hypotonic buffer was used to burst the outer membrane, and Triton X-100 was used to disrupt all membranes. OM, outer membrane; IMS, intermembrane space; IM, inner membrane. (E) Quantitation of the wild-type and mutant ANT1 pools that are protected from PK degradation in intact mitochondria. All HA levels were normalized by TFAM, then plotted as relative to its untreated sample. Replicates from three independent transfections. p-Values were calculated with a one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (F) ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D obstruct general mitochondrial protein import. Proteomics of the cytosolic fraction of transfected HeLa cells reveals increase in mitochondrial proteins caused by ANT1A114P-HA and ANT1A114P,A123D-HA expression relative to ANT1-HA. p-Values were calculated with a Student’s t test of the average abundance levels of each mitochondrial protein. (G) Volcano plot comparing the cytosolic proteome of SLC25A4 p.A114P,A123D vs SLC25A4-transfected HeLa cells. Data represented as mean ± SEM. (H) Enrichment analysis of proteins significantly increased in the cytosol of SLC25A4 p.A114P,A123D-transfected HeLa cells. Depicted are the most significant enriched protein groups generated from three different databases: GO: Biological Process (top), KEGG pathway (middle), and GO: Molecular Function (bottom).

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Proteomic comparison of the cytosolic fraction of SLC25A4 p.A114P,A123D- versus SLC25A4-transfected HeLa cells.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig5-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 5—source data 2

Uncropped Western blots from Figure 5A,B,D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig5-data2-v2.zip

Regarding the function of the non-mitochondrial proteins increased in the cytosol of ANT1A114P,A123D-expressing cells, we found that the most significantly enriched Biological Process, Molecular Function, and KEGG pathway were ‘chaperone’, ‘stress response’, and ‘protein processing in the ER’ (Figure 5H). This may represent a stress response directed toward the increased mitochondrial protein burden in the cytosol.

An alternative explanation for reduced protein import in mutant Ant1-transfected cells is general mitochondrial damage and/or apoptosis activation leading to reduced Δψ, which would also cause a reduction in protein import. However, neither ANT1A114P,A123D nor its single mutant counterparts reduced Δψ or significantly increased cell death compared with wild-type (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). Thus, the effect on protein import by ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D is likely due to their physical retention in the import pathway rather than due to reduction of Δψ. It is interesting that ANT1A114P,A123D does not increase apoptosis in the immortalized HeLa cells, despite clearly clogging protein import. This may be related to the transient nature of ANT1 expression or an inherent resistance of the immortalized cells to cell death.

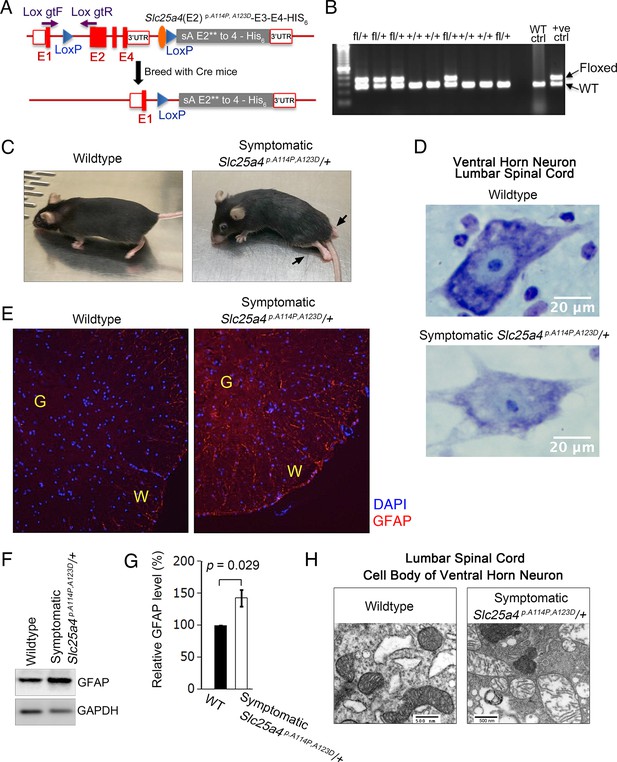

Ant1A114P,A123D causes dominant muscle and neurological disease in mice

We generated a knock-in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ (expressing Ant1A114P,A123D) mouse line to model protein import clogging in vivo (Figure 6A–B). We observed a neurodegeneration phenotype that culminates in paralysis in some Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice (Figure 6C; Video 1; Video 2). This phenotype occurred in only four Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice, with a penetrance of 3.4% among the heterozygous mice that have reached 15 months of age. The presenting symptom is typically altered gait after the age of 11 months, followed by weight loss and death within 2–3 weeks of symptom onset. Histological analysis of the lumbar spinal cord in a symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse demonstrated dissolution of Nissl substance in the cell bodies of ventral horn neurons (Figure 6D), consistent with motor neuron degeneration (Bodian and Mellors, 1945). Neurodegeneration in the spinal cord was also indicated by GFAP accumulation by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting (Figure 6E–G). Transmission electron microscopy of ventral horn neurons revealed loss of cristae density of mitochondria, which suggests defects in mitochondrial biogenesis (Figure 6H).

Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse generation and neurodegeneration.

(A) Schematic of the strategy by which the knock-in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ knock-in mice were generated. E1–E4, exons 1–4 of Slc25a4. In gray is the inserted cDNA containing two missense mutations in exon 2, followed by the endogenous 3’ UTR. Lox gtF and gtR indicate genotyping primers. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR genotyping using genotyping primers indicated in (A). Fl, floxed. (C) Ascending paralytic phenotype of an Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse at 11 months of age, and its wild-type littermate. Arrows point to paralyzed hindlimbs. (D) Nissl-stained lumbar spinal cord neuron of a symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse and wild-type littermate. This neuron shows loss of Nissl substance and blurring of nuclear boundaries, process known as ‘chromatolysis’, which indicates neuron degeneration. (E) Indirect immunofluorescence for the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) indicating spinal cord gliosis in a symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse. G, gray matter; W, white matter. (F) Immunoblot analysis of lumbar spinal cord lysate confirmed increase in GFAP in symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. (G) Quantitation from (F) showing significant increase in GFAP in the spinal cord of a symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse indicating neuroinflammation. p-Value was calculated from Student’s t test. (H) Transmission electron microscopy of a ventral horn neuron of a symptomatic Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse and wild-type littermate control.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Uncropped Western blots from Figure 6F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig6-data1-v2.zip

Paralytic phenotype of an Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse at the age of 12 months.

Paralytic phenotype of an Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse at the age of 16 months.

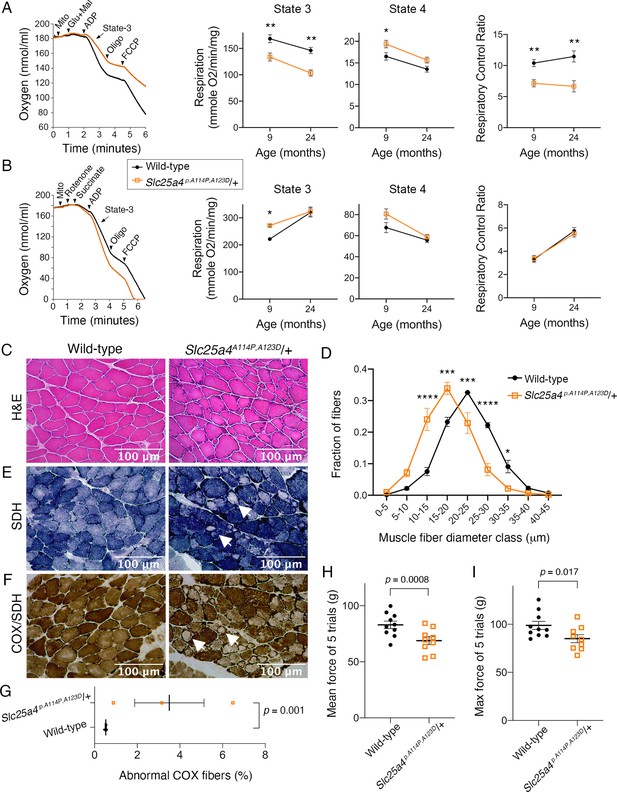

Dominant SLC25A4-induced diseases primarily affect skeletal muscle in addition to low-penetrant neurological involvement (Kaukonen et al., 2000; Siciliano et al., 2003; Simoncini et al., 2017; Kaukonen et al., 1999; Napoli et al., 2001; Deschauer et al., 2005). Key muscle features include mildly reduced mitochondrial respiratory function, COX-deficient muscle fibers, and muscle weakness. Consistent with clinical phenotypes, we found that the maximal respiratory rate (state 3) of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ muscle mitochondria was reduced by ~20% and ~30% when utilizing complex I in 9- and 24-month-old mice, respectively (Figure 7A). The respiratory control ratio, which is the single most useful and sensitive general measure of energy coupling efficiency (Brand and Nicholls, 2011), was reduced by ~31% and ~42% in young and old mice, respectively. Surprisingly, when complex I is inhibited and complex II substrate (succinate) is present, maximal respiration is increased by ~23% in the mutant mice at 9 months of age (Figure 7B). This result is important because it confirms that ATP/ADP transport is not a limiting factor for sustaining a high respiratory rate in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice.

Ant1A114P,A123D (encoded by Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D) causes a dominant mitochondrial myopathy in mice.

(A) Respirometry of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria with complex I stimulated by glutamate (glu) and malate (mal). State 3, maximal respiratory rate after addition of ADP; state 4, oligomycin (oligo)-inhibited respiratory rate; respiratory control ratio = state 3/state 4. N=6 mice/genotype at 9 months of age; n=4 mice per genotype at 24 months of age. Three measurements were taken per mouse. p-Values were derived from repeated measures ANOVA with measurement order as the within-subjects variable. Data from two age groups were analyzed independently. FCCP, trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone. (B) Respirometry of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria with complex II stimulated by succinate and complex I inhibited by rotenone. N=2 mice/genotype at 9 months of age, 4 measurements/mouse; n=4 mice/genotype at 24 months of age, 3 measurements/mouse. Data analyzed as in (A). (C) Soleus muscles stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) showing smaller myofibers in 30-month-old Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. (D) Feret’s diameter analysis of H&E stained soleus in (C) reveals atrophy in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. At least 340 myofibers were measured per soleus. Myofiber diameters were binned into 5 μm ranges and plotted as % of total. N=3 mice/genotype. Data analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) histochemical activity staining of the soleus showing abnormal fibers that stain for SDH peripherally but are pale internally (arrows). (F) Histochemical cytochrome c oxidase (COX) and SDH sequential staining of the soleus shows abnormal fibers that stain for COX peripherally, but do not stain for COX or SDH internally. (G) Quantitation of abnormal COX fibers shown in (F). p-Value was calculated from Student’s t test. (H) Forelimb grip strength is reduced in 30-month-old Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. p-Value from Student’s t test. (I) Maximal forelimb grip strength is reduced in 30-month-old Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. p-Value from Student’s t test. Data represented as mean ± SEM.

In addition to mild bioenergetic defect, we detected significant reduction in myofiber diameter in the skeletal muscle from aged Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice (Figure 7C–D). Sequential COX/SDH histochemical assay failed to detect any COX-negative/SDH-positive fibers in the aged Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ muscles. Instead, we found that ~3.5% of myofibers have reduced COX and SDH activity centrally, but remained COX and SDH-positive in the periphery (Figure 7E–G). Finally, we found that the Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice display muscle weakness (Figure 7H–I). These data demonstrate that Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D induces a dominant myopathic phenotype.

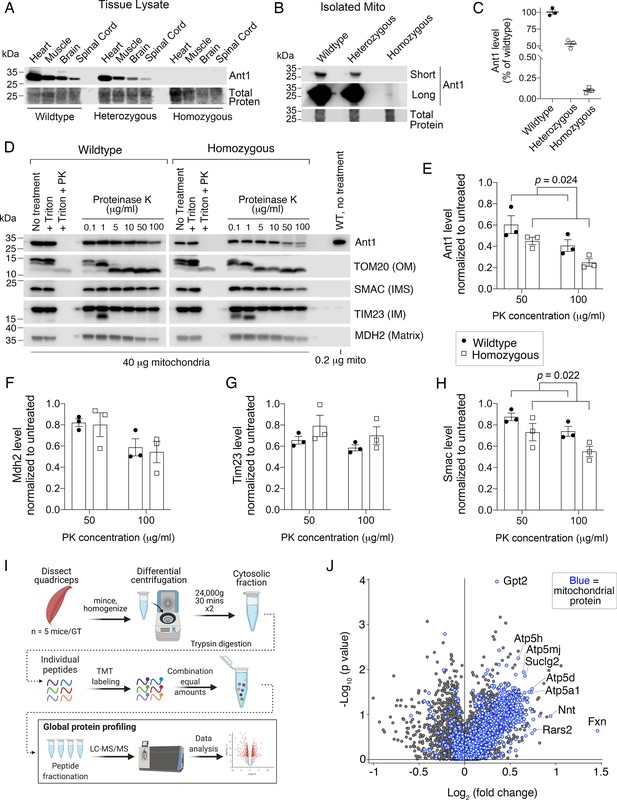

Ant1A114P,A123D clogs protein import in vivo

For biochemical characterization of the mutant protein, we turned to homozygous Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D mice as to eliminate the detection of confounding wild-type Ant1. We found that the Ant1A114P,A123D protein is virtually undetectable in the total lysates of mouse tissues, suggesting a rapid degradation of the mutant protein as observed in yeast and human cells. (Figure 8A). Only in isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria were we able to detect Ant1A114P,A123D, which was present at ~0.1% of wild-type level (Figure 8B–C). Protease protection assay on isolated muscle mitochondria demonstrated that Ant1A114P,A123D is more sensitive to proteinase K digestion compared with wild-type Ant1 (Figure 8D–E), consistent with import clogging in vivo. Moreover, Smac also appears to be more sensitive to proteinase K in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D mitochondria, while Mdh2 and Tim23 do not (Figure 8F–H). While this could indicate instability or partial rupture of the OMM in mutant mitochondria, it could also be a result of clogging and imply that clogging does not affect all mitochondrial preproteins equally. Consistent with this concept, our experiments in yeast showed minimal effects of clogging on Ilv5p, a mitochondrial matrix protein, in contrast to Hsp60p (Figure 1F; Figure 2H–I). This could be explained by the observation that the Tom40 β-barrel pore contains several distinct protein paths (Shiota et al., 2015; Araiso et al., 2019).

Ant1A114P,A123D clogs protein import in vivo.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of tissue lysate showing low Ant1A114P,A123D protein levels in heterozygous and homozygous mice. (B) Immunoblot analysis of isolated muscle mitochondria demonstrating low Ant1A114P,A123D protein levels. (C) Quantitation of Ant1 levels in isolated muscle mitochondria from three mice per genotype, as determined by immunoblotting. Values were normalized to total protein stain and shown as relative to wild-type. (D) Ant1A114P,A123D is more sensitive to proteinase K (PK) than wild-type Ant1 in intact mitochondria. Immunoblot analysis after PK protection assay of isolated muscle mitochondria in isotonic buffer. Ant1A114P,A123D was detected using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (top right panel). (E–H) Quantitation from protease protection assay, as shown in (D). n=3 mice per genotype. p-Values were calculated with a two-way ANOVA, showing significant main effect of genotype. Data represented as mean ± SEM. (I) Schematic of tandem mass tagged (TMT) quantitative proteomic analysis. (J) Volcano plot comparing the cytosolic proteome of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ vs wild-type skeletal muscle, with mitochondrial proteins highlighted in blue.

-

Figure 8—source data 1

Proteomic comparison of the cytosolic fraction of 30-month-old skeletal muscle from Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ versus wild-type mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig8-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 8—source data 2

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/84330/elife-84330-fig8-data2-v2.zip

Finally, to test if Ant1A114P,A123D obstructs general mitochondrial protein import in vivo, we compared the cytosolic proteomes of aged muscle from wild-type and Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice using tandem mass tagged (TMT) quantitative proteomics (Figure 8I). We found a striking global increase in mitochondrial proteins in the cytosol of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ muscle (Figure 8J). Among the 75 proteins increased by at least 25% in the cytosol (p<0.05), proteins assigned to the mitochondrion accounted for 45 of them (Figure 8—source data 1). This enrichment was highly significant (FDR<10–33). Taken together, the data suggest that Ant1A114P,A123D clogs general protein import in vivo. Supporting this is a trend of increase in proteasomal subunits and Hsp70 proteins in the cytosol of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+muscle, which suggests an anti-mPOS response (Figure 8—figure supplement 1A–B).

To evaluate the impact of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D expression on mitochondrial proteostasis, we assessed the assembly state of protein complexes and supercomplexes in the inner membrane with native gel electrophoresis. The respiratory complexes and supercomplexes were minimally affected (Figure 8—figure supplement 1C–D), as was the TIM23 complex (Figure 8—figure supplement 1E). To gain a global view of mitochondrial proteostasis, we performed TMT labeling quantitative proteomics on mitochondrial fractions from skeletal muscle. We found minimal changes in the steady-state levels of mitochondrial proteins, including other Ant isoforms (Figure 8—figure supplement 1F, Figure 8—figure supplement 1—source data 1). This may reflect highly efficient degradation of Ant1A114P,A123D, which is suggested by its steady-state level being 0.1% of wild-type (Figure 8B–C). It is also consistent with the subtle bioenergetic defects and the overall mild neuronal and muscular phenotypes associated with the Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice. Interestingly, a focused analysis on mitochondrial proteases and chaperones suggested a subtle but statistically significant increase in the mitochondrial proteostatic machinery (p=2.7 × 10–14, analyzed with a two-way ANOVA; Figure 8—figure supplement 1G), which supports proteostatic stress inside mitochondria.

Another possible explanation for minimal changes in mitochondrial proteins in the context of protein import clogging could be increased protein import TIM22 pathway. Our mitochondrial proteomics dataset suggested global increase in TIM22 pathway components (Figure 8—figure supplement 1H). Immunoblot validation of Tim22 showed an ~40% increase (Figure 8—figure supplement 1I–J). These data may represent chronic adaptation to carrier protein import clogging, though more work is required to rigorously test this hypothesis.

Transcriptional response induced by Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D expression in mouse muscle

The integrated stress response (ISR) is activated by a diverse range of mitochondrial insults. Surprisingly, we found no evidence of ISR activation downstream of Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D expression. First, eIF2α phosphorylation, a hallmark of the ISR, was not increased in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse skeletal muscle at multiple ages (Figure 8—figure supplement 2A–B). Second, transcriptomic analysis in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ skeletal muscle failed to show induction of ISR target genes (Figure 8—figure supplement 2C). Instead, transcription factor enrichment analysis of significantly upregulated genes (q<0.05) revealed activation of pathways controlled by novel transcriptional factors, including FOXO1 and FOXO3 that are involved in metabolic homeostasis and autophagy (Figure 8—figure supplement 2D–E). It appeared that Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D induces an entirely unique transcriptional signature (Figure 8—figure supplement 2F; Figure 8—figure supplement 2—source data 1), although it remains to be determined whether severe mitochondrial protein import clogging relative to Ant1A114P,A123D induces similar stress responses and/or activates ISR. Among the upregulated genes, Depp1 is known to activate autophagy (Stepp et al., 2014). More importantly, when directly compared to Slc25a4 knockout mice (Morrow et al., 2017), there is very limited overlap in the enrichment profile among significantly altered genes (Figure 8—figure supplement 2G). This indicates that the primary stress in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ skeletal muscle is distinct from that in Ant1 knockout mice.

In summary, we found that Ant1A114P,A123D dominantly causes muscle and low-penetrant neurological disease in mice that recapitulates pathological and molecular phenotypes of dominant Ant1-induced diseases in humans. This corroborates the toxicity of Aac2A128P,A137D in yeast (Figure 1), and supports the idea that mitochondrial protein import clogging by a mutant substrate preprotein is pathogenic.

Discussion

Failure in mitochondrial protein import has severe physiological consequences. In addition to defective mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism, it also causes toxic accumulation and aggregation of mitochondrial preproteins in the cytosol, a process termed mitochondrial Precursor Overaccumulation Stress (mPOS) (Wang and Chen, 2015; Coyne and Chen, 2018; Song et al., 2021). To prevent these consequences, many cellular safeguards have been identified that can maintain protein import efficiency and/or mitigate mPOS (Backes et al., 2021; Weidberg and Amon, 2018; Boos et al., 2019; Izawa et al., 2012; Wrobel et al., 2015; Nargund et al., 2015; Izawa et al., 2017; Hansen et al., 2018; Zurita Rendón et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Mårtensson et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019; Ordureau et al., 2020; Phu et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021; Shakya et al., 2021; Xin et al., 2022; Sam et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2023; Dewar et al., 2022; Krämer et al., 2023). So far, studies on mitochondrial stressors that impair protein import have been mainly focused on mutations that directly affect the core protein import machinery, synthetic clogger proteins, or on pharmacological interventions that reduce Δψ (Song et al., 2021). In this report, we have uncovered the first example of naturally occurring missense mutations in an endogenous mitochondrial protein causing toxic protein import clogging. We showed that a single protein without overexpression is sufficient to clog import, thereby inducing robust protein import stress responses, bioenergetic defects, and cytosolic proteostatic stress. The data supports a model in which import clogging kills yeast cells and contributes to muscle and neurological degeneration in mice.

Mitochondrial protein import can be clogged by a mutant mitochondrial preprotein

The mitochondrial carrier protein family is the largest of the transporter families and has highly conserved domain and sequence features across all eukaryotes. Their import into mitochondria is unique in that they assume partially folded conformations called ‘hairpin loops’ that place adjacent hydrophobic α-helices antiparallel with one another (de Marcos-Lousa et al., 2006; Wiedemann et al., 2001). There are three ‘hairpin loop’ modules per carrier preprotein that transit through the Tom40 β-barrel in a loop-first topology, such that the C- and N-termini initially remain exposed to the cytosol. This leaves little wiggle room for the carrier preprotein considering the Tom40 β-barrel can only accommodate the width of up to two α-helical segments at a time (Wiedemann et al., 2001). To get through the Tom40 β-barrel pore, the hydrophobic hairpin loops are thought to be guided by an array of hydrophobic patches on the inside of the pore (Shiota et al., 2015; Araiso et al., 2019). It is in the hydrophobic α-helices of the ADP/ATP translocase ANT1 (Aac2p in yeast) that dominant pathogenic mutations are found, which introduce either a proline or an aspartic acid (see Figure 1). Here, we show that these mutations cause the protein to arrest at or in the TOM complex, thereby partially obstructing general protein import. There are multiple potential mechanisms. First, as the mutations introduce a proline or aspartic acid into the hydrophobic α-helix, it may simply be loss of the necessary hydrophobic interaction with the inner surface of the Tom40 β-barrel pore. Another possibility is that the hairpin loop structure is disrupted such that it becomes too wide to fit through the narrow pore. This may be particularly relevant for the proline mutants which would introduce a kink into the α-helix. A third possibility is that mutant ANT1/Aac2p is not impaired in transit through the pore, but instead is inefficiently chaperoned by the small TIM chaperones in the IMS, leading to ‘backpressure’ in the pathway. Interestingly, carrier preproteins appear to form partial α-helical secondary structures while bound to the Tim9-Tim10 chaperone (Weinhäupl et al., 2018). Future work will be essential to rigorously decipher between these potential mechanisms of clogging.

The data strongly suggest that double mutant Aac2p preferentially clogs the TOM complex (Figure 2). In contrast, co-immunoprecipitation of single mutants Aac2pA128P and ANT1A114P showed increased association with both the TOM and TIM22 complexes. We interpret these data with caution, as it would be unexpected that single mutants would clog at multiple locations. However, it is possible that hairpin loops and/or hydrophobic α-helices are crucial for interaction with both complexes. As the precise mechanism of import and IMM insertion by the TIM22 complex remains unresolved, it would be premature to speculate on potential clogging mechanisms.

One of the most surprising observations of this study was the extreme toxicity of the double mutant clogger proteins that arrest at the TOM complex. The deleterious stressors downstream of clogging are likely to be multifactorial and include respiratory defects and cytosolic protestatic stress via mPOS. While it is possible that general proteostasis is perturbed by Aac2pA128P,A137D saturating proteolytic machinery, our data suggest this is unlikely. The IMM-associated AAA protease Yme1p (and not the proteasome) appears to be a major proteolytic pathway for clogged Aac2pA128P,A137D. That genetic deletion of YME1 is well tolerated in yeast cells suggests that loss of Yme1-based proteolysis does not underlie toxicity of aac2A128P,A137D expression. We propose that clogging of the TOM complex is the primary mechanism of Aac2pA128P,A137D-induced protein import defects and the ensuing cell stress. Importantly, the former is strongly supported by in vitro experiments showing that Aac2pA128P,A137D is defective in translocating through the TOM complex in fully energized, wild-type mitochondria.

In the context of low Aac2pA128P,A137D levels in cells (just 4.7% of wild-type), it is important to note that the ADP/ATP carrier is one of the most abundant proteins in mitochondria, outnumbering the Tom40 pore-forming protein by almost an order of magnitude (Morgenstern et al., 2017; Pfanner et al., 2019). Thus, if ~70% of the reduced level of Aac2pA128P,A137D is actively clogging TOM complexes, this would still occupy ~30% of the Tom40 channels, which may have a considerable effect on general protein import. This reflects the central importance of proper TOM complex function to mitochondrial and cell homeostasis, and also provides physiological justification for the existence of multiple pathways dedicated to unclogging the TOM complex (Weidberg and Amon, 2018; Mårtensson et al., 2019).

It will be interesting to determine whether and how Yme1 plays a general role in quality control of the TIM22 import pathway. Yme1 degradation of Aac2pA128P,A137D could occur at the TOM complex, in association with the small TIMs or at the TIM22 complex. A functional crosstalk between Yme1p and the TIM22 complex has been proposed (Hwang et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2023). Detailed mechanistic studies are required.

Mitochondrial protein import clogging as a mechanism of disease

A long-standing mystery in the mitochondrial disease field is how dominant mutations in SLC25A4 (encoding adenine nucleotide translocase 1 [Ant1]) cause such a wide spectrum of clinical and molecular phenotypes that are not observed in patients with homozygous null SLC25A4 (Kaukonen et al., 2000; Siciliano et al., 2003; Simoncini et al., 2017; Palmieri et al., 2005; Napoli et al., 2001; Deschauer et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2016; Echaniz-Laguna et al., 2012; Tosserams et al., 2018; Kashiki et al., 2022). The implication is that the dominant pathogenic ANT1 proteins must have an unknown gain-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Similarly, the phenotypes observed in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice cannot be explained by haploinsufficiency or a dominant negative effect on ADP/ATP transport for the following reasons. First, as in humans, the neurological and muscle phenotypes in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice have never been reported in heterozygous Slc25a4 knockout mice despite 25 years of characterization by Doug Wallace and colleagues. Second, mitochondria from Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mouse muscle are able to exceed the maximal respiration rate of wild-type mitochondria when complex II is stimulated (Figure 6B), indicating that one functional copy of Ant1 is sufficient to support high respiratory rates without compensatory increase in other Ant isoforms (see Figure 8—figure supplement 1F; Figure 8—figure supplement 1—source data 1; Figure 8—figure supplement 2—source data 1; Figure 8—figure supplement 2F). This is in stark contrast to Slc25a4 knockout, which displays a >30% reduction in complex II-based respiration (Graham et al., 1997). Third, the transcriptional profile in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ skeletal muscle is entirely distinct from that in Slc25a4 knockout mice, suggesting different underlying mechanisms of muscle dysfunction (Morrow et al., 2017). Fourth, Ant1 likely functions as a monomer, making a dominant-negative mechanism of adenine nucleotide transport unlikely (Pebay-Peyroula et al., 2003; Ruprecht et al., 2019; Kunji and Ruprecht, 2020). Finally, the yeast equivalent of Ant1A114P,A123D, Aac2pA128P,A137D, is catalytically inactive yet clearly exerts toxicity even in conditions where aac2Δ cells are healthy (Figure 1C). Taken together, the evidence is clear that dominant SLC25A4 mutations cause gain-of-function phenotypes in patients, Slc25a4 p. A114P,A123D/+ mice and yeast models.

In this study, we elucidated a candidate molecular mechanism of dominant Ant1-induced disease using yeast, human cells, and a novel mouse model. We found that pathogenic ANT1 mutations modeled in yeast’s Aac2p cause the protein to clog global mitochondrial protein import leading to respiratory defects, cytosolic proteostatic stress (Wang and Chen, 2015), and loss of cell viability. Combining two mutations into a single Ant1 protein drastically enhanced clogging activity, which tightly correlated with toxicity. We extensively characterized one such ‘super-clogger’ variant, Aac2pA128P,A137D, and found that the main clogging site shifted to the TOM complex, providing an explanation for the increased toxicity. Protein import clogging was strikingly consistent in transfected human cells, as ANT1A114P and ANT1A114P,A123D (ortholog of yeast Aac2pA128P,A137D) physically associated with the TOM and TIM22 complexes, was exposed on the outside of intact mitochondria, and caused mitochondrial protein retention in the cytosol. Even in mice, Ant1A114P,A123D expression correlated with retention of mitochondrial proteins in the cytosol despite minute levels of the mutant protein, presumably due to degradation. Finally, we found that Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice phenocopy ANT1-induced autosomal dominant progressive external opthalmoplegia (adPEO) patients, as Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice exhibit mild OXPHOS defects, partially COX-deficient myofibers, moderate myofiber atrophy, and muscle weakness (Kaukonen et al., 1999; Komaki et al., 2002). The low-penetrant neurodegeneration in Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D/+ mice may also reflect human disease process, as a neurodegenerative phenotype has been reported in an adPEO patient carrying the SLC25A4 p.A114P allele (Simoncini et al., 2017). Taken together, these data strongly argue that protein import clogging contributes to adPEO in humans, despite Slc25a4 p.A114P,A123D not directly genocopying a particular clinical condition. We do note, however, that additional contributory mechanisms and even SLC25A4 deficiency cannot be completely excluded without in vivo rescue experiments.

In summary, we demonstrate that pathogenic mutations in a mitochondrial carrier protein can cause clogging of the protein import pathway, which induces multifactorial cellular stress and correlates with cell toxicity and disease in mice. These findings uncovered a vulnerability of the mitochondrial protein import machinery to single amino acid substitutions in mitochondrial inner membrane preproteins. There are 53 carrier proteins in human mitochondria that have highly conserved domain organization both within and across species (Palmieri et al., 2011). Mutations altering conformational elements involved in protein import, such as hairpin loops, are likely strongly selected against during evolution. Those persisting in the human population would affect protein import and cause disease, as exemplified by the dominant pathogenic mutations in SLC25A4.

Our work provides just a first glimpse into the amino acid requirements of mitochondrial carrier proteins to maintain compatibility with the mitochondrial protein import machinery. Future work will be crucial to systematically evaluate the amino acid requirements first within ANT1/Aac2p, and then across entire carrier protein family. It will also be important to determine which specific interactions with protein import components are affected by different mutations. Overall, these efforts may enable the prediction of pathogenic mechanisms of future variants of uncertain significance as they arise with more exome sequencing of human patients.

Materials and methods

Key resources table - see Appendix 1.

Yeast growth conditions and genetic manipulation

Request a detailed protocolYeast cells were grown using standard media. Genotypes and sources of yeast strains are listed in Key resources table. To generate the AAC2 expression plasmids, we amplified the gene from total genomic DNA and inserted it into pFA6a-ScAAC2-URA3-HIS3/2. The missense mutations were introduced using QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis (Stratagene) and mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Mutant genes were then cloned into pRS416 for expression (Figure 1B) and pFA6a-KanMX6 for placing next to the KAN selection marker. The aac2A128P,A137-KAN cassette was then amplified for integration into the LYS2 locus of the W303-1B strain background. All strains in Figure 1C–E were derived from this strain by standard genetic crosses. All combinations of aac2 mutations were expressed by transforming an equal number of M2915-6A yeast with freshly prepared pRS416-based vectors (URA3) expressing wild-type or mutant aac2. Equal fractions of the transformant culture were plated on selective medium lacking uracil and grown at 25°C or 30°C for 3 days before being photographed (, Figure 1B and S1A ). tom70Δ and tim18Δ strains were generated by amplification of the knockout cassette from genomic DNA of tom70Δ and tim18Δ strains from BY4741 knockout library, followed by transformation into M2915-6A by selecting for G418R. The disruption of the genes was confirmed by PCR using an independent primer pair surrounding the native genomic locus. PRE9 and UMP1 were disruption in strains of W303 background by the insertion of kan. These alleles were then introduced into strains expressing aac2A128P, A137D by genetic crosses. For galactose-induced expression, AAC2 and its mutant alleles were placed under the control of the GAL10 promoter in the integrative vector pUC-URA3-GAL. The resulting plasmids were then linearized by cutting with StuI within the URA3 gene, before being integrated into the ura3-1 locus by selecting for Ura+ transformants. Correct chromosomal integration was confirmed by examining the stability of the Ura+ phenotype and PCR amplification of the URA3 locus. The yme1Δ and pdr5Δ alleles were introduced into these strains either by direct gene disruption or by genetic crosses.

Cell lysis, western blotting, and signal quantitation

Request a detailed protocolUnless otherwise noted, yeast cells were lysed and prepared for SDS-PAGE as previously described (Chen, 2001). HeLa cells and mouse tissues were lysed with RIPA buffer containing 1× HALT Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher) and prepared for SDS-PAGE with Laemmli buffer. Standard procedures were used for chemiluminescent western blot detection of proteins. Membranes were imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey imager and signals quantitated in the associated ImageStudio software.

Detergent extraction of potential insoluble protein

Request a detailed protocolWe took two approaches to detecting potentially aggregated Aac2pA128P,A137D. First, spheroplasts were generated using zymolyase followed by lysis in sample buffer (containing 8 M urea+5% SDS) with or without 2% Sarkosyl. Second, the insoluble material from our typical lysis procedure (see above) was treated with different detergents. For formic acid, pellet was resuspended in 100% formic acid, incubated at 37°C for 70 min, followed by speed-vac drying of the sample and resuspension in sample buffer for SDS-PAGE. For guanidine dissociation, pellet was resuspended in 8 M guanidine HCl, incubated at 25°C for 70 min, then sodium deoxycholate was added to a final concentration of 1%. Protein was then precipitated with TCA, washed with acetone at –20°C, and resuspended in sample buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Affinity chromatography

Request a detailed protocolHis-tagged Aac2p affinity purification was performed on 1 mg mitochondria per replicate. Yeast mitochondria were isolated as previously described (Diekert et al., 2001). Mitochondria were lysed in ‘lysis buffer’ (10% glycerol, 1.5% digitonin, 50 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and a protease inhibitor cocktail) including 100 mM NaCl (‘low salt’) or 200 mM NaCl (‘high salt’) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Lysate was centrifuged at 21,000×g for 30 min. Imidazole was added to supernatant for a final concentration of 4 mM, which was applied to preequilibrated Ni-NTA agarose beads (QIAGEN) and rotated at 4°C for 2 hr. Beads were then washed three times with ‘lysis buffer’ (including the corresponding NaCl) but with 0.1% digitonin. Protein was eluted from the beads with 300 mM imidazole, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol in 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4). For mass spectrometry, samples were briefly run into an SDS-PAGE gel. Whole lanes were excised, and protein was subject to in-gel trypsin digestion. To ensure reproducibility, the eluate used for mass spectrometry was derived from two independent mitochondrial preparations per strain, and affinity chromatography was performed on 2 separate days.

HA-tagged ANT1 affinity purification was performed on whole-cell lysate. Each replicate was from an independent transfection of a 10 cm dish of HeLa cells. Briefly, 24 hr after transfection, cells were collected, washed twice in cold PBS, and then lysed in 0.5 mL lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 1% digitonin, 1 mM PMSF, and 1× HALT Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher)) for 30 min on ice. Lysate was cleared for 30 min at 16,000×g, and supernatant applied to preequilibrated Pierce anti-HA agarose beads (Thermo Fisher) and incubated overnight with gentle agitation. Beads were subsequently washed five times with lysis buffer, except containing 0.1% digitonin, followed by elution with 6% SDS and 10% glycerol, in 50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4.

Sample processing for mass spectrometry

Request a detailed protocolThe excised lanes of yeast eluate (see above) were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion (Shevchenko et al., 2006). Briefly, gel pieces were washed with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Acros) in 50% acetonitrile (ACN) (Fisher), reduced with dithiothreitol (Acros) and alkylated with iodoacetamide (Sigma), washed again, and impregnated with 75 µL of 5 ng/µL trypsin (trypsin gold; Promega) solution overnight at 37°C. The resulting peptides were extracted using solutions of 50% and 80% ACN with 0.5% formic acid (Millipore), and the recovered solution dried down in a vacuum concentrator. Dried peptides were dissolved in 60 µL of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, Sigma), and desalted using 2-core MCX stage tips (3 M) (Rappsilber et al., 2003). The stage tips were activated with ACN followed by 3% ACN with 0.1% TFA. Next, samples were applied, followed by two washes with 3% ACN with 0.1% TFA, and one wash with 65% ACN with 0.1% TFA. Peptides were eluted with 75 µL of 65% ACN with 5% NH4OH (Sigma), and dried.

Cytosolic fractions from HeLa cells were processed using the FASP method (Wiśniewski et al., 2009). Briefly, in-solution proteins were reduced and denatured with DTT and SDS, mixed with urea to 8 M, and concentrated on a 10 kDa MWCO membrane filter (Pall, OD010C34). Cysteine residues were alkylated using iodoacetamide (Sigma) at room temperature in a dark location for 25 min. The proteins were rinsed with urea and ammonium bicarbonate solutions and digested overnight at 37°C using trypsin gold (Promega) at a ratio of 1:100. The resulting peptides were recovered from the filtrate and a 10 µg aliquot was desalted on 2-core MCX stage tips as above.

LC-MS methods

Request a detailed protocolSamples were dissolved in 20–35 µL of water containing 2% ACN and 0.5% formic acid to 0.25 µg/µL. Two µL (0.5 µg) were injected onto a pulled tip nano-LC column with 75 µm inner diameter packed to 25 cm with 3 µm, 120 Å, C18AQ particles (Dr. Maisch). The column was maintained at 45°C with a column oven (Sonation GMBH). The peptides were separated using a 60 min gradient from 3–28% ACN over 60 min, followed by a 7 min ramp to 85% ACN. The column was connected inline with an Orbitrap Lumos via a nanoelectrospray source operating at 2.2 kV. The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent top speed mode with a cycle time of 2.5 s. MS1 scans were collected at 60,000 resolution with AGC target of 6.0E5 and maximum injection time of 50 ms. HCD fragmentation was used followed by MS2 scans in the Orbitrap at 15,000 resolution with AGC target 1.0E4 and 100 ms maximum injection time.

Database searching and label-free quantification

Request a detailed protocolThe MS data was searched using SequestHT in Proteome Discoverer (version 2.4, Thermo Scientific) against the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome from Uniprot, containing 6637 sequences, concatenated with common laboratory contaminant proteins. Enzyme specificity for trypsin was set to semi-tryptic with up to two missed cleavages. Precursor and product ion mass tolerances were 10 ppm and 0.6 Da, respectively. Cysteine carbamidomethylation was set as a fixed modification. Methionine oxidation was set as a variable modification. The output was filtered using the Percolator algorithm with strict FDR set to 0.01. Label-free quantification was performed in Proteome Discoverer with normalization set to total peptide amount.

Label-free quantitation data processing

Request a detailed protocolFor analysis, label-free quantitation with Proteome Discoverer software generated protein abundances for each sample. Protein abundances were then analyzed using Metaboanalyst software (Pang et al., 2020). First, we refined the protein list to include only proteins whose fold-change is >1.5 (p<0.1) in Aac2p-HIS6 eluate compared with the null control. Then, to eliminate any bias introduced by mutant bait protein Aac2pA128P-HIS6 being present at ~50% the level of Aac2-HIS6 (see Figure 4—figure supplement 1C; Figure 4—figure supplement 2A), we normalized each prey protein abundance by that sample’s bait protein level (i.e. Aac2p level). Finally, we performed multiple t testing on these values, which generated the FDR-corrected p-values and were ultimately normalized to wild-type level for presentation in Figure 4C, Figure 4—figure supplement 1I, Figure 4—figure supplement 2B and E. Gene Ontology (GO) and other enrichment analyses were performed using STRING version 11.0 (Szklarczyk et al., 2019).

For the analysis shown in Figure 5F, the protein list was manually curated to include only proteins that had a GO Cellular Component term for ‘mitochondrion’, and not that of any other organelle. Proteins with missing values were excluded. The levels of each protein were averaged within an experimental group and those average values were normalized to the average value for wild-type SLC25A4-transfected samples. It is these wild-type-normalized average values for each protein that were subject to Student’s t test to probe for a significant difference in mitochondrial protein levels present in the cytosol of mutant compared with wild-type SLC25A4-transfected HeLa cells.

Targeted quantitative proteomics

Request a detailed protocolUnused yeast peptides from the label-free quantification experiment were used for absolute quantification using parallel reaction monitoring on the instrument described above. The instrument method consisted of one MS scan at 60,000 resolution followed by eight targeted Orbitrap MS2 scans at 30,000 resolution using quadrupole isolation at 1.6 m/z and HCD at 35%.

Two heavy-labeled proteotypic peptides for Aac2p and Tim22p were purchased from New England Peptide. Their sequences were TATQEGVISFWR and SDGVAGLYR; and VYTGFGLEQISPAQK and TVQQISDLPFR, respectively, each with N-terminal 13C6 15N4 arginine or 13C6 15N2 lysine. An equal portion of the peptides contained in each gel band was combined with a mixture of proteotypic peptides resulting in an on-column load of 1 fmol of each Tim22p heavy peptide and 250 fmol of each Aac2p heavy peptide. Assays were developed for the doubly charged precursor and the four or five most intense singly charged product y-ions. The data was analyzed in Skyline (version 20.2) (MacLean et al., 2010).

qRT-PCR

Request a detailed protocolTotal RNA was isolated from ~1.5×107 yeast cells using Quick-RNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (Zymo Research). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was executed using 50 ng RNA in Power SYBR Green RNA-to-Ct 1-step Kit (Applied Biosystems). A CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) was used with the following cycling parameters: 48°C 30 min, 95°C 10 min, followed by 44 cycles of 95°C 15 s, 60°C 1 min. TFC1 was used as reference, as its mRNA level was previously established as stable across culture conditions (Teste et al., 2009). The specificity of each primer pair was validated using RNA extracted from knockout strains. Ct values were determined using CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad) and analyzed manually using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

In vitro mitochondrial protein import assays

Request a detailed protocolThe AAC2 variants were cloned into pGEM4z plasmids. The constructs were used for coupled in vitro transcription and translation, using a cell-free system based on reticulocyte lysate. The wild-type strains YPH499 and BY4741 and yeast expressing Tom40-HA were grown in YPG (1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] bacto-peptone, and 3% [vol/vol] glycerol) at 30°C. Mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation. The import of the Aac2p variants were performed as described (Ellenrieder et al., 2019). Isolated mitochondria were incubated for different time periods with radiolabeled Aac2p variants in the presence of 4 mM ATP and 4 mM NADH in import buffer (3% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin; 250 mM sucrose; 80 mM KCl; 5 mM MgCl2; 5 mM methionine; 2 mM KH2PO4; 10 mM MOPS/KOH, pH 7.2). The import reaction was stopped by addition of 8 µM antimycin A, 1 µM valinomycin, and 20 µM oligomycin (AVO; final concentrations). In control reactions, the membrane potential was depleted by addition of the AVO mix. Subsequently, mitochondria were washed with SEM buffer (250 mM sucrose; 1 mM EDTA; 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2), lysed with 1% (wt/vol) digitonin in lysis buffer (0.1 mM EDTA; 50 mM NaCl; 10% [vol/vol] glycerol; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) for 15 min on ice analysis and protein complexes were separated on blue native gels. To remove non-imported preproteins, mitochondria were treated with 50 µg/mL proteinase K for 15 min on ice. The protease was inactivated by addition of 1 mM PMSF for 10 min on ice. To study the accumulation of Aac2p variants at the TOM translocase, the Aac2p variants were imported into Tom40-HA mitochondria followed by affinity purification via anti-HA beads (Roche) (Ellenrieder et al., 2019). After the import reaction, mitochondria were lysed with 1% (wt/vol) digitonin in lysis buffer for 15 min on ice. After removing insoluble material, the mitochondrial lysate was incubated with anti-HA matrix for 60 min at 4°C. Subsequently, beads were washed with an excess amount of 0.1% (wt/vol) digitonin in lysis buffer and bound proteins were eluted under denaturing conditions using SDS sample buffer (2% [wt/vol] SDS; 10% [vol/vol] glycerol; 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue; 0.2% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol; 60 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8).

Pulse-chase analysis of Aac2pA128P, A137D