Kinetochore inactivation by expression of a repressive mRNA

Abstract

Differentiation programs such as meiosis depend on extensive gene regulation to mediate cellular morphogenesis. Meiosis requires transient removal of the outer kinetochore, the complex that connects microtubules to chromosomes. How the meiotic gene expression program temporally restricts kinetochore function is unknown. We discovered that in budding yeast, kinetochore inactivation occurs by reducing the abundance of a limiting subunit, Ndc80. Furthermore, we uncovered an integrated mechanism that acts at the transcriptional and translational level to repress NDC80 expression. Central to this mechanism is the developmentally controlled transcription of an alternate NDC80 mRNA isoform, which itself cannot produce protein due to regulatory upstream ORFs in its extended 5’ leader. Instead, transcription of this isoform represses the canonical NDC80 mRNA expression in cis, thereby inhibiting Ndc80 protein synthesis. This model of gene regulation raises the intriguing notion that transcription of an mRNA, despite carrying a canonical coding sequence, can directly cause gene repression.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.27417.001eLife digest

DNA stores the genetic information needed to make proteins and other molecules inside cells. To make a protein, cells use a particular section of DNA as a template to make molecules of messenger RNA (or mRNA for short), which are then translated into the corresponding protein.

Inside yeast, humans and other eukaryotic organisms, DNA is organized into structures called chromosomes. When these cells divide to make sex cells, such as egg cells and sperm, they undergo a process known as meiosis to make four daughter cells with only half as many chromosomes as the parent cell. During meiosis the parent cell’s chromosomes need to be separated twice in quick succession. Large assemblies of proteins known as kinetochores are essential for this process. At the beginning of meiosis the kinetochores are inactive, which prevents the chromosomes from being separated too soon. Later on, the kinetochores are activated to allow the chromosomes to be separated. In budding yeast cells, control of kinetochore activity is achieved by regulating the levels of a single protein within the kinetochore known as Ndc80. It was not clear, however, how this regulation occurs.

Chen, Tresenrider et al. show that two yeast mRNAs with opposing activities are the key to regulating when Ndc80 is produced during meiosis. These two mRNAs carry the same protein-coding message but one mRNA is longer and contains an extension that prevents it from being translated into protein. The sole role of the longer mRNA is to prevent the shorter mRNA from being produced. The longer mRNA is only made in early meiosis, which prevents new Ndc80 proteins from being made during this time and results in the kinetochores being inactivated. The chromosomes only separate when production of the shorter mRNA returns later in meiosis and higher levels of Ndc80 protein allow the kinetochores to reform.

These findings demonstrate that even if an mRNA molecule does carry protein-coding information, it may not actually act as a messenger to make that protein, but instead, it can serve a regulatory role by blocking that protein’s production. The key components involved in regulating Ndc80 during meiosis are found in many organisms ranging from yeast to humans, suggesting that similar mechanisms could be used to control proteins involved in other processes in cells.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.27417.002Introduction

Cellular differentiation programs depend on temporally controlled waves of gene activation and inactivation. These waves in turn drive the morphogenetic events that ultimately transform one cell type into another. Differentiation models ranging from Bacillus subtilis sporulation to mouse embryogenesis have elucidated how transcription factor handoffs temporally activate the expression of gene clusters (Errington, 2003; Zernicka-Goetz et al., 2009). In comparison, much less is understood about how gene repression is coordinated with the transcription factor-driven waves of gene expression and how this inactivation is mechanistically achieved.

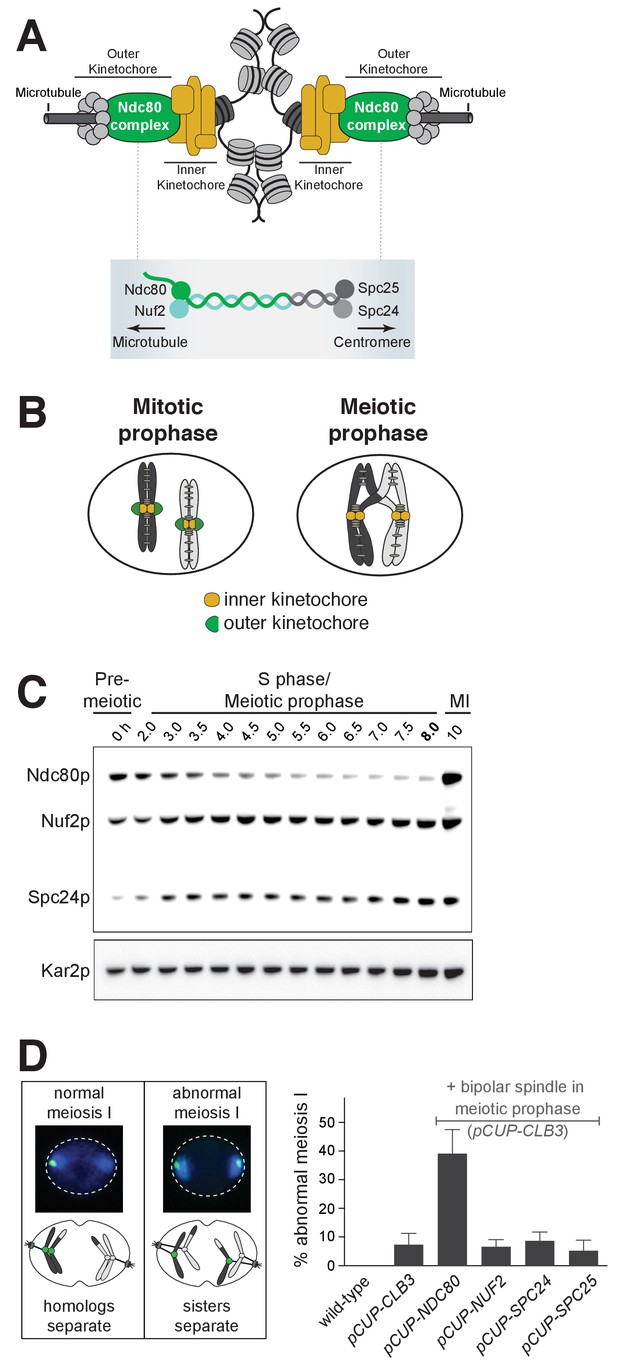

One critical morphogenetic event that relies on inactivation is the loss of kinetochore function during meiotic prophase. The kinetochore is a protein complex that binds to centromeric DNA and serves as the attachment site for spindle microtubules to mediate chromosome segregation (Musacchio and Desai, 2017) (Figure 1A). In multiple systems, it has been shown that kinetochores do not bind to microtubules in meiotic prophase (Asakawa et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2011). Furthermore, this temporal inactivation is achieved through removal of the outer kinetochore, the site where microtubule attachments occur (Asakawa et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2011) (Figure 1B). In the presence of a spindle, cells that fail to disassemble the outer kinetochore undergo catastrophic missegregation of meiotic chromosomes, underlying the essential nature of kinetochore downregulation during meiotic prophase (Miller et al., 2012). Importantly, the kinetochore is reactivated when the outer kinetochore reassembles upon transition from prophase to the meiotic divisions. How the initial removal and subsequent reassembly of the outer kinetochore is coordinated with the meiotic gene expression program is unknown.

Kinetochore function is repressed during meiotic prophase due to limiting levels of Ndc80.

(A–B) Schematics of kinetochore structure and dynamic behavior. (A) Top: kinetochores assembled on the centromere and attached to microtubules. Bottom: the Ndc80 complex. (B) During mitosis, the outer kinetochores are fully assembled, while in meiotic prophase, the outer kinetochores disassemble. (C) Ndc80, Nuf2, and Spc24 protein abundance in meiosis. Anti-V5 immunoblotting was performed at the indicated time points for three epitope-tagged subunits of the Ndc80 complex (Ndc80-3V5, Nuf2-3V5, and Spc24-3V5) in a single strain (UB4361). Using the pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER synchronization method (Carlile and Amon, 2008), cells were arrested in pachytene and then released 8 hr after the cells were transferred to SPO to allow progression into the meiotic divisions. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. (D) Sister chromatid segregation in wild type (UB4432), pCUP-CLB3 (UB4434), pCUP-CLB3 pCUP-NDC80 (UB880), pCUP-CLB3 pCUP-NUF2 (UB4436), pCUP-CLB3 pCUP-SPC24 (UB980), and pCUP-CLB3 pCUP-SPC25 (UB885). A pair of sister chromatids of chromosome V was labeled with the centromeric TetO/TetR-GFP system (CENV-GFP). Left: A schematic depicting CENV-GFP dot localization in normal and abnormal meiosis I. In normal meiosis I, when homologous chromosomes segregate, a single GFP dot is present in one of the two nuclear masses of a binucleated cell. In abnormal meiosis I, when sister chromatids segregate, both nuclear masses of a binucleated cell contain a GFP dot. Right: The average fraction of binucleates that displayed sister chromatid segregation in meiosis I. Expression of Clb3 and each Ndc80 complex subunit (both regulated by the pCUP promoter) were co-induced by addition of CuSO46 hr after the cells were transferred to SPO. Concomitantly, cells were released from pachytene arrest by addition of β-estradiol. Cells were fixed 1 hr and 45 min after the release. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean from three independent experiments. 100 cells were counted per strain, per experiment.

Budding yeast provides a powerful model to address how the dynamic regulation of kinetochore function is integrated into the meiotic gene expression program. Entry into meiosis marks a clear cell-fate transition defined by the induction of Ime1, a master transcription factor. Ime1 activates the expression of genes involved in DNA replication and meiotic recombination (Kassir et al., 1988; van Werven and Amon, 2011). Successful completion of recombination, in turn, induces a second transcription factor Ndt80, which activates the expression of genes involved in meiotic divisions and gamete development (Chu and Herskowitz, 1998; Xu et al., 1995). Thus, the landmark morphogenetic events in budding yeast meiosis are coordinated by the relay between these two transcription factors. Furthermore, a high-resolution map of the gene expression waves that drive meiosis has been generated for budding yeast (Brar et al., 2012). Importantly, analysis of this dataset revealed that, of the 38 genes that encode kinetochore subunits, NDC80 displays the most regulated expression pattern between meiotic prophase and the subsequent division phases (Miller et al., 2012).

Ndc80 is the namesake member of an evolutionarily conserved complex that forms the microtubule-binding interface of the outer kinetochore (Tooley and Stukenberg, 2011) (Figure 1A). Numerous lines of evidence indicate that the tight regulation of NDC80 is essential for the timely function of kinetochores during meiosis. First, the decline of Ndc80 protein in meiotic prophase correlates with the dissociation of the outer kinetochore from the chromosomes (Kim et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012). Second, even though the other outer kinetochore subunits are expressed in meiotic prophase, they do not localize to the kinetochores (Meyer et al., 2015). Third, the subsequent increase in Ndc80 protein coincides with outer kinetochore reassembly (Meyer et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012). Finally, in the presence of a spindle, prophase misexpression of NDC80 disrupts proper meiotic chromosome segregation (Miller et al., 2012). Together, these results indicate that NDC80 regulation is necessary for the proper timing of kinetochore function in meiosis and highlight the importance of controlling Ndc80 protein levels during meiotic differentiation.

Here we uncovered how the timely function of kinetochores is achieved through the regulation of Ndc80 protein synthesis during budding yeast meiosis. This mechanism is based on the use of two NDC80 mRNA isoforms, which have opposite functions and display distinct patterns of expression. In addition to the canonical protein-translating NDC80 mRNA, we found that meiotic cells also expressed a 5’-extended NDC80 isoform. Despite carrying the entire NDC80 open reading frame (ORF), this alternate isoform cannot produce Ndc80 protein due to the presence of regulatory upstream ORFs (uORFs) in its extended 5’ leader. Rather, its transcription plays a repressive role to inhibit transcription of the canonical NDC80 mRNA in cis and thereby inhibit Ndc80 protein synthesis. Furthermore, we found that the expression of the 5’-extended isoform was activated by the meiotic initiator transcription factor Ime1. Upon exit from prophase, the mid-meiotic transcription factor Ndt80 activated the expression of the canonical NDC80 mRNA isoform. Taken together, this study uncovers how NDC80 gene repression is achieved and how inactivation and subsequent reactivation of the kinetochore is coordinated with the transcription factor-driven waves of meiotic gene expression.

Results

Ndc80 is the limiting component for kinetochore function in meiotic prophase

The Ndc80 complex consists of four subunits, namely Ndc80, Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25 (Figure 1A). All the subunits other than Ndc80 persist in meiotic prophase (Meyer et al., 2015). Consistent with this report, we found that even in an extended meiotic prophase arrest, Ndc80 was the only subunit of its complex whose abundance decreased at this meiotic stage (Figure 1C and Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25 were all expressed, though it has been reported that these proteins fail to localize to the kinetochores during meiotic prophase (Meyer et al., 2015).

These observations raised the possibility that Ndc80 could be the limiting kinetochore subunit in meiosis. If correct, then the elevation of Ndc80 protein levels, but not the other subunits, should reactivate kinetochore function in meiotic prophase. To test this prediction, we overexpressed each of the Ndc80 complex subunits (Figure 1—figure supplement 2), in conjunction with the B-type cyclin Clb3, under an inducible CUP1 promoter (pCUP). CLB3 misexpression causes bipolar spindle assembly in meiotic prophase (Miller et al., 2012). In pCUP-CLB3 cells, if kinetochores are functional in meiotic prophase, they attach to the spindle microtubules prematurely. These premature attachments, in turn, cause sister chromatid segregation in meiosis I, essentially disrupting proper meiotic chromosome segregation (Miller et al., 2012). When NDC80 was overexpressed in pCUP-CLB3 cells during meiotic prophase, over 30% of the cells displayed an abnormal segregation pattern in meiosis I. In contrast, misexpression of CLB3 alone resulted in only a 7% segregation defect. Importantly, this defect was not further enhanced by the overexpression of NUF2, SPC24 or SPC25 (Figure 1D). Based on this observation, we conclude that kinetochore function is repressed in meiotic prophase due to limiting levels of Ndc80. Following prophase, Ndc80 becomes highly abundant during the meiotic divisions (Miller et al., 2012) (Figures 1C, 10 h time point), consistent with its role in facilitating chromosome segregation (Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001). Together, these results demonstrate that Ndc80 is the sole subunit of its complex that is tightly regulated during meiotic differentiation and strongly support the notion that NDC80 downregulation and re-synthesis govern kinetochore functionality in meiosis.

Two distinct NDC80 transcript isoforms exist in meiosis

To dissect the molecular mechanism for the strict temporal regulation of the NDC80 gene in meiosis, we first took advantage of the high-resolution RNA-seq and ribosome profiling dataset generated for budding yeast meiosis (Brar et al., 2012). Analysis of this dataset revealed the presence of meiosis-specific RNA-seq reads that extend to ~500 base pairs (bp) upstream of the NDC80 ORF (Figure 2A). These reads appeared after meiotic entry and persisted until the end of meiosis, but were absent during vegetative growth (Figure 2—figure supplement 1, vegetative) or starvation (Figure 2—figure supplement 1, MATa/MATa).

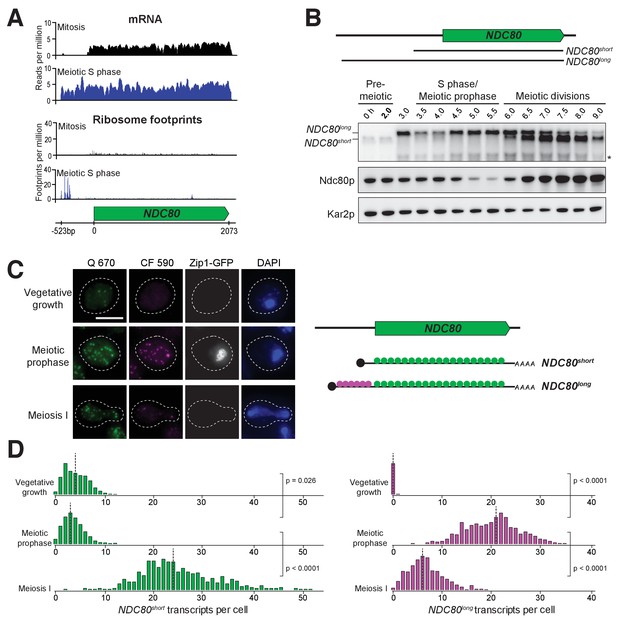

Two distinct NDC80 transcripts are expressed during meiosis.

(A) Ribosome profiling and mRNA-seq reads over the NDC80 locus during vegetative growth (top track) or meiotic S phase (bottom track). Data are derived from (Brar et al., 2012). (B) NDC80 mRNA isoforms and Ndc80 levels in meiosis. NDC80long and NDC80short levels were determined by northern blot, and Ndc80 level was determined by anti-V5 immunoblot at the indicated time points. To induce meiotic entry, IME1 and IME4 expression was induced in the strain UB1337 by addition of CuSO4 2 hr after cells were transferred to SPO. SCR1, loading control for northern blot. Kar2, loading control for immunoblot. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. * indicates a smaller RNA product, which likely represents a truncated form of NDC80long. (C) Representative smFISH images for NDC80long and NDC80short during vegetative growth and meiosis. Vegetative samples were taken when cells (UB8144) were growing exponentially in nutrient rich medium. Meiotic prophase samples were taken 6 hr after cells (UB8144) were transferred to SPO, a time when these cells were arrested in pachytene using the pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER system. Cells were then released by addition of β-estradiol, and meiosis I samples were taken 1.5 hr later. The Q 670 probes (shown in green) hybridize to the common region shared between NDC80long and NDC80short, whereas the CF 590 probes (shown in magenta) hybridize to the unique 5’ region of NDC80long (schematic is shown in the right panel). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Each cell was staged by its Zip1-GFP signal. Vegetative growth: Zip1-GFP negative. Meiotic prophase: Zip1-GFP positive. Meiosis I: Zip1-GFP negative and post NDT80 induction. Images here and throughout are shown as the maximum-intensity projections of z-stacks. Scale bar: 5 µm. (D) Quantification of smFISH data shown in (C), graphed as the relative frequency histograms of cells with a given number of NDC80long and NDC80short transcripts per cell, using data pooled from three independent experiments. The dashed line indicates the median number of NDC80long and NDC80short transcripts per cell. Each histogram here and throughout was normalized so that the maximum bin height is the same across all histograms. A total number of 637 cells were analyzed for vegetative growth, 437 for meiotic prophase, and 491 for meiosis I. Two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was performed between each pair of conditions as indicated by the bracket. Refer to Supplementary file 1F for a summary of the median transcript levels for all the smFISH experiments.

To monitor the different RNA molecules generated from the NDC80 locus, we performed northern blotting. In the absence of meiotic progression, when cells were subject to nutrient poor conditions, we detected only a single NDC80 transcript throughout the starvation regime (no CuSO4, Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). However, in cells undergoing synchronous meiosis, two distinct NDC80 transcript isoforms became evident: a longer, meiosis-specific isoform, and a shorter isoform that was also present under non-meiotic conditions (Figure 2B and Figure 2—figure supplement 2). The longer isoform appeared after meiotic entry, persisted throughout meiotic prophase and gradually disappeared during the meiotic divisions. The shorter isoform was present in vegetative cells prior to meiotic entry, but was weakly expressed during S phase and meiotic prophase. Its abundance dramatically increased during the meiotic divisions (Figure 2B and Figure 2—figure supplements 2B and 3). Interestingly, the Ndc80 protein levels were noticeably higher during the meiotic stages when the shorter transcript was the predominant isoform, but lower when the longer transcript was predominant (Figure 2B).

In addition to northern blotting, we used single molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) to assess the cell-to-cell variability in transcript expression and subcellular localization of these two NDC80 transcript isoforms. With two sets of probes that bind to the same region of NDC80 ORF (odd/even probes), we verified that our smFISH could uniquely pair the FISH spots from these two probe sets with an accuracy of 88% (Figure 2—figure supplement 4), a value similar to what was reported previously (Raj et al., 2008). Furthermore, we confirmed that the number of cells analyzed per sample per experimental repeat (>95 cells) exceeded the minimal number of cells required to achieve a stable sampling average (Figure 2—figure supplement 5), and thus our sample size is large enough to reflect the population mean.

To differentiate between the two NDC80 isoforms, we used another two sets of probes: one set (Q 670), conjugated to Quasar 670, is complementary to the sequences common between the short and the long isoforms. The other set (CF 590), conjugated to CAL Fluor Red 590, is unique to the long isoform. The long isoforms were identified as the spots where the signal from both probe sets colocalized, whereas the short isoforms were identified as the spots with signal only from Q 670 (Figure 2C and D).

The smFISH analysis revealed that the expression of the two NDC80 isoforms was temporally regulated. Vegetative cells expressed only the short NDC80 isoform; fewer than 2% of these cells expressed the long isoform (Figure 2C and D). In meiotic prophase, a stage defined by the presence of the synaptonemal complex component Zip1, 100% of cells expressed the long isoform, and over 50% of them had more than 20 transcripts per cell. During the same stage, the level of the short isoform significantly decreased in comparison to its levels in vegetative growth (p=0.0260, two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, Figure 2D) and pre-meiotic starvation (p=0.0090, Figure 2—figure supplement 6). As cells entered meiosis I, the level of the short isoform dramatically increased while that of the long isoform declined, in comparison to the levels of these isoforms during meiotic prophase (p<0.0001 for both NDC80short and NDC80long mRNAs, Figure 2D). Thus, the two NDC80 isoforms have expression signatures specific to different cellular states.

In addition, the two NDC80 isoforms localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure 2C). We saw no evidence that the NDC80long isoform was solely retained in the nucleus; all of the Zip1-positive cells had at least one NDC80long mRNA localized outside of the DAPI-stained region. This localization pattern was consistent with the possibility that both transcripts were translated, as shown by ribosome profiling (Figure 2A, bottom panel) (Brar et al., 2012).

Altogether, the combined analyses of northern and western blotting, as well as smFISH, reveal two interesting trends: (1) In meiosis, the expression of the long and short NDC80 isoforms are anti-correlated. (2) Ndc80 protein levels positively correlate with the presence of the short isoform and negatively correlate with the long isoform (Figure 2B).

The long NDC80 isoform is unable to produce Ndc80 protein due to translation of its upstream ORFs

The negative correlation between the longer NDC80 isoform and Ndc80 protein levels suggested that this longer isoform was unable to support the synthesis of Ndc80 protein. In addition to the NDC80 ORF, the longer isoform contains nine uORFs, each with an AUG start codon. The first six of these uORFs, those closest to the 5’ end of the mRNA, have ribosome profiling signatures consistent with them being translated in meiosis (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Upstream start codons in transcript leaders can capture scanning ribosomes to alternate reading frames, thereby restricting ribosome access to the main ORF (Arribere and Gilbert, 2013; Calvo et al., 2009; Johnstone et al., 2016).

We mutated the start codon of the first six uORFs (∆6AUG) to test whether translation of the uORFs within the longer NDC80 isoform represses translation of Ndc80 protein from this mRNA. In the ∆6AUG strain, the negative correlation between the long isoform and Ndc80 protein level persisted (Figure 3), potentially because translation of the remaining three uORFs could still repress translation of the ORF. Indeed, when all nine AUGs were mutated, Ndc80 protein became highly abundant during meiotic prophase, even though the long isoform remained the predominant NDC80 transcript in these cells (Figure 3). These results demonstrate that although the longer isoform of NDC80 contains the entire ORF, the presence of the uORFs in its 5’ leader prevents Ndc80 translation from this mRNA.

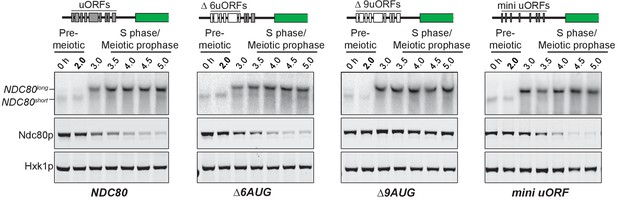

The longer NDC80 mRNA isoform is unable to synthesize Ndc80 protein due to translation of its AUG uORFs.

(A) NDC80short, NDC80long, and Ndc80 abundance during synchronous meiosis (as described in Figure 2B) in wild type (UB6190), Δ6AUG (UB6181), Δ9AUG (UB6183), and mini uORF (UB9243) strains. In the Δ6AUG and Δ9AUG strains, the first 6 or 9 uORF AUGs in the 5’ leader of NDC80long were converted to AUCs, respectively. The mini uORF construct contained all 9 uORF start sites in the NDC80long leader; however, the third codon of each of the 9 uORFs was mutated to a stop codon. One of the two repeated experiments is shown.

Next, we tested whether the repressive role of the uORFs resulted from the act of translation or the peptides encoded by these uORFs. We modified the long isoform, such that it still contained all the upstream AUG start codons, but each start codon was followed by a single amino acid and then immediately by a stop codon (mini uORF). Thus, this construct retained the translation ability of the uORFs but rendered them incapable of producing a peptide chain. We found that Ndc80 levels were still reduced during meiotic prophase in the mini uORF strain (Figure 3). Therefore, translation of the uORFs represses translation of the NDC80 ORF from the long NDC80 isoform, rendering this isoform unable to synthesize Ndc80 protein.

Our analyses so far demonstrate that the two NDC80 mRNA isoforms differ with regards to their size and ORF coding capacity. The shorter isoform is capable of translating NDC80 ORF. In contrast, although the longer isoform contains the entire ORF, it does not support Ndc80 synthesis. The coding information is not decoded from this isoform because uORF translation prevents ribosomes from accessing the actual ORF. To signify the unique features of each NDC80 transcript isoform, we named the short mRNA NDC80ORF, and the longer mRNA NDC80luti for long un-decoded transcript isoform.

NDC80luti expression in cis is necessary and sufficient to downregulate NDC80ORF

Given that NDC80luti does not appear to produce Ndc80 protein, we set out to understand why meiotic cells express this mRNA isoform. Based on the observation that the expression levels of these two isoforms are anti-correlated, we posited that the transcription of NDC80luti represses NDC80ORF. To test this hypothesis, we first eliminated NDC80luti production by deleting its promoter along with different portions of the NDC80luti transcript (∆NDC80luti, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). As shown by northern blotting, NDC80ORF was detected during meiotic prophase in two different ∆NDC80luti mutant strains (Figure 4A and Figure 4—figure supplement 2). Analysis of smFISH also confirmed that the level of NDC80ORF in ∆NDC80luti cells significantly increased during meiotic prophase (Figure 4B and C, p=0.0004), with a median exceeding that of pre-meiotic cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 6). Accordingly, Ndc80 protein levels increased throughout meiotic prophase (Figure 4A).

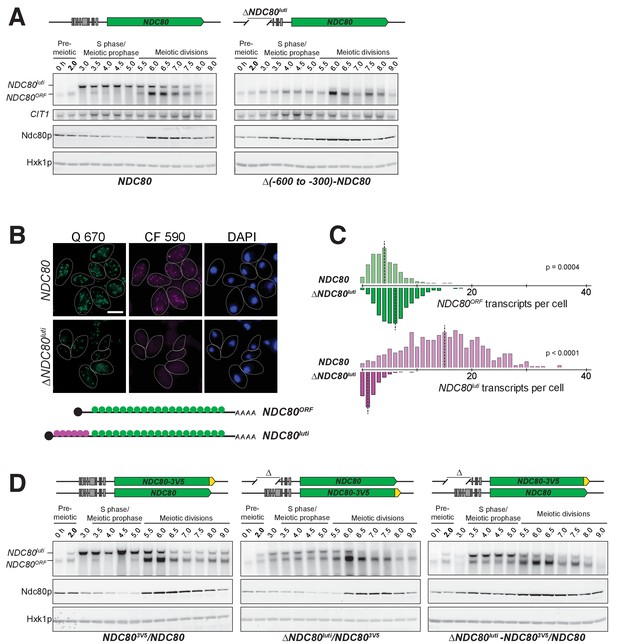

NDC80luti is necessary to downregulate NDC80ORF.

(A) NDC80ORF, NDC80luti, and Ndc80 abundance during synchronous meiosis (as described in Figure 2B) in wild type cells (FW1902) and in ΔNDC80luti cells (FW1871), in which 300–600 bp upstream of the Ndc80 translation start site were deleted. Ndc80 level was determined by anti-V5 immunoblot. CIT1, loading control for northern blot. Hxk1, loading control for immunoblot. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. (B) Representative smFISH images for NDC80luti and NDC80ORF during meiotic prophase in wild type cells (UB6190) and in ΔNDC80luti cells (UB6079), in which 479–600 bps upstream of the Ndc80 translation start site were deleted. This deletion construct was used, as opposed to the (−600 to −300) deletion, because this construct retains all the binding sites for the CF 590 probes (bind to the unique region of NDC80luti). Samples were taken 2 hr after IME1 and IME4 induction in a synchronous meiosis and hybridized with the Q 670 probes (bind to the common region of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF, shown in green) and the CF 590 probes (shown in magenta), as in Figure 2C. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 5 µm. (C) Quantification of smFISH data shown in (B), graphed as the relative frequency histograms of cells with a given number of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF transcripts per cell, using data pooled from three independent experiments. The dashed line indicates the median number of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF transcripts per cell. A total number of 611 cells were analyzed for wild type and 649 for ∆NDC80luti. Two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was performed for NDC80ORF and NDC80luti, respectively, comparing wild type with ∆NDC80luti during meiotic prophase. (D) NDC80luti represses NDC80ORF expression in cis. Meiosis was induced and samples were collected and processed as in (A). Ndc80 level was determined by anti-V5 immunoblot. Hxk1, loading control. Three yeast strains were used in this experiment: 1) a strain (FW1900) with one NDC80-V5 allele and one wild type NDC80 allele (left), 2) a strain (FW1899) with one NDC80-3V5 allele and one ΔNDC80luti allele, in which 300–600 bp upstream of the Ndc80 translation start site were deleted (middle), and 3) a strain (FW1923) with one ΔNDC80luti-NDC80-3V5 allele, which has the aforementioned 300–600 bps deletion, and one wild type NDC80 allele (right). One of the two repeated experiments is shown.

Additionally, we inserted a termination sequence ~220 bp downstream of the NDC80luti transcription start site (NDC80luti-Ter). We observed that, upon early termination of NDC80luti, NDC80ORF mRNA and Ndc80 protein persisted in meiotic prophase (Figure 4—figure supplement 3). This observation suggests that continuous transcription through the NDC80ORF promoter is necessary for NDC80ORF repression. It also indicates that the repression of NDC80ORF is not due to competition between the NDC80ORF promoter and the NDC80luti promoter for RNA polymerase and the general transcription machinery. Altogether, we conclude that expression of the NDC80luti mRNA is required to repress the NDC80ORF transcript and reduce Ndc80 protein levels during meiotic prophase.

By what mechanism does NDC80luti reduce the steady-state level of NDC80ORF? We posited that NDC80luti acts in cis based on other instances of overlapping transcription in budding yeast (Bird et al., 2006; Martens et al., 2004; van Werven and Amon, 2011). To test this, we engineered strains to have one wild type NDC80luti allele and another allele in which the promoter of NDC80luti has been deleted (∆NDC80luti). In order to monitor Ndc80 protein levels, we inserted a 3V5 epitope as a C-terminal fusion to NDC80 in either the wild type or the ∆NDC80luti allele. If NDC80luti functions in trans, then Ndc80-3V5 should be downregulated to the same extent in both strains. Instead, we found that Ndc80-3V5 was downregulated only when NDC80luti was generated on the same chromosome, directly upstream of NDC80-3V5 (Figure 4D, middle panel). This result demonstrates that NDC80luti-mediated repression occurs in cis, since NDC80luti cannot reduce Ndc80 protein expression from a copy of NDC80 on another chromosome (Figure 4D, right panel). In the accompanying manuscript, Chia et al. revealed that this cis-acting mechanism is a result of alterations to the chromatin landscape across the NDC80ORF promoter caused by NDC80luti transcription (Chia et al., 2017).

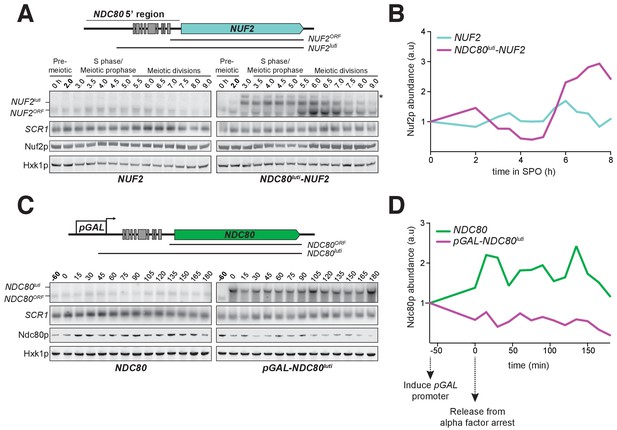

Since NDC80luti is necessary to repress NDC80ORF during meiosis, we next investigated whether the NDC80luti leader is sufficient to regulate other genes in meiosis. We replaced the promoter and 5’ leader of NUF2, the gene encoding the binding partner of Ndc80, with the promoter and 5’ leader region of NDC80luti (NDC80luti-NUF2). In wild type cells, a single NUF2 mRNA species was expressed in meiotic prophase, a stage when NUF2 mRNA levels and Nuf2 protein levels were stable (Figure 5A and B). In contrast, NDC80luti-NUF2 cells expressed a longer mRNA (NUF2luti) in meiotic prophase (Figure 5A), and the abundance of NUF2ORF transcripts was reduced by ~60% compared to that in the pre-meiotic stage (Figure 5—figure supplement 1), a reduction level similar to that of the Nuf2 protein (Figure 5B). This result demonstrates that the promoter and 5’ leader sequence of NDC80luti is sufficient to downregulate another protein in meiotic prophase.

NDC80luti is sufficient to downregulate NDC80ORF.

(A) A luti-mRNA is produced by the NDC80luti-NUF2 fusion construct (NUF2luti) in meiosis. To generate the NDC80luti-NUF2 construct, the promoter and leader sequence of NDC80luti (1000 bps directly upstream of the NDC80 ORF start site) was placed immediately upstream of the NUF2 coding region. NUF2luti and NUF2ORF expression was detected by northern blot, and Nuf2 was detected by anti-V5 immunoblot. SCR1, loading control for northern blot. Hxk1, loading control for immunoblot. Samples were taken when the wild type (UB5103) and NDC80luti-NUF2 (UB5101) cells were undergoing synchronous meiosis. * indicates a band of unknown origin. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. (B) Quantification of Nuf2 protein abundance from the experiment shown in (A). For each time point, Nuf2 signal was first normalized to Hxk1. This normalized value was set to 1 for the 0 hr time point (t0), and all the subsequent time points were calibrated relative to t0. (C) NDC80ORF, NDC80luti, and Ndc80 levels when NDC80luti is expressed in synchronous mitosis. MATa wild type control (UB2389) and pGAL-NDC80luti (UB2388) cells, both harboring the Gal4-ER fusion protein, were arrested in G1 with α-factor. pGAL expression was induced 2 hr later by addition of β-estradiol (−60 min). One hour after the β-estradiol addition (0 min), cells were released from G1 arrest. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. (D) Quantification of Ndc80 abundance from the experiment shown in (C). For each time point, Ndc80 signal was first normalized to Hxk1. This normalized value was set to one for the first time point at −60 min (t-60, the time of β-estradiol addition) and all the subsequent time points were then calibrated relative to t-60.

As NDC80luti expression is naturally restricted to meiosis, we tested whether the expression of NDC80luti was sufficient to downregulate NDC80ORF outside of meiosis. We artificially expressed NDC80luti during mitosis, a time when NDC80luti is naturally absent. We engineered strains in which the sole copy of the NDC80 gene had a modified upstream region, such that the endogenous promoter of NDC80luti was replaced by the inducible GAL1-10 promoter (pGAL-NDC80luti). This alteration had minimal effect on cell growth (Figure 8C, uninduced), suggesting that NDC80ORF transcript and Ndc80 protein expression is largely unaffected in the absence of induction. In wild type cells synchronously progressing through the mitotic cell cycle, a single mRNA isoform, NDC80ORF, was present at all stages (Figure 5C, left panel). In contrast, the NDC80ORF transcript became undetectable in pGAL-NDC80luti cells one hour after NDC80luti induction (Figure 5C, right panel). Four hours after induction, Ndc80 protein levels were reduced to 20% of the initial level, while in wild type cells it was increased to 116% (Figure 5D). Based on these data, we conclude that NDC80luti expression is sufficient to repress NDC80ORF outside of meiosis. The reduction in NDC80ORF expression, in turn, causes reduced synthesis of Ndc80 protein, thus essentially turning off the NDC80 gene.

Master meiotic transcription factors Ime1 and Ndt80 regulate NDC80luti and NDC80ORF expression, respectively

Since the timely expression of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF is crucial to establish the temporal pattern of Ndc80 protein levels in meiosis, we next investigated which transcription factors directly control NDC80luti and NDC80ORF expression. In S. cerevisiae, meiotic gene expression is orchestrated by two master transcription factors: Ime1 and Ndt80 (Chu and Herskowitz, 1998; Kassir et al., 1988; Xu et al., 1995). Diploid MATa/MATα cells initiate meiosis by expressing IME1 in response to nutrient deprivation (van Werven and Amon, 2011). Interestingly, IME1 expression correlated with the time of NDC80luti expression, suggesting that Ime1 might regulate NDC80luti transcription. Indeed, deletion of IME1 abolished NDC80luti production and resulted in persistent levels of NDC80ORF transcript and Ndc80 protein (Figure 6A and Figure 6—figure supplement 1).

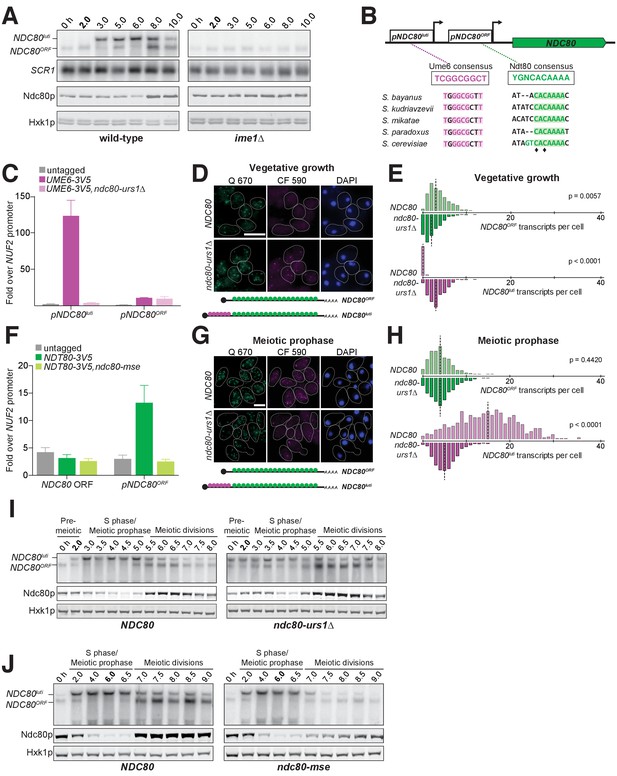

The meiosis-specific transcription factors Ime1 and Ndt80 regulate NDC80luti and NDC80ORF, respectively.

(A) NDC80ORF, NDC80luti, and Ndc80 abundance during meiosis in pCUP-IME1 pCUP-IME4 (FW1902) and pCUP-IME4 ime1∆ (FW3058) cells. Expression from the pCUP promoter was induced 2 hr after cells were transferred to SPO. One of the two repeated experiments is shown. (B) Putative Ume6 (URS1) and Ndt80 (MSE) binding sites are present in the intergenic region upstream of NDC80. Colored bases match the consensus binding sequences. Highlighted areas indicate the conserved regions across all five Saccharomyces species by Clustal analysis (RRID:SCR_001591). The black diamonds indicate the two sites mutated from C to A in the ndc80-mse strain. (C) Ume6-3V5 chromatin immunoprecipitation in untagged (UB2531), UME6-3V5 (UB3301), and UME6-3V5 ndc80-urs1∆ (UB6760) strains. Cells were harvested after overnight growth in BYTA. The DNA fragments recovered from the Ume6-3V5 ChIP were quantified by qPCR using two primer pairs: one specific for the NDC80luti promoter and one specific for the NDC80ORF promoter. Enrichment at these loci was normalized to the signal from the NUF2 promoter, to which Ume6 does not bind. The mean fold enrichment over the NUF2 promoter from three independent experiments, as well as the standard error of the mean, is displayed. (D) Representative smFISH images for NDC80luti and NDC80ORF during vegetative growth in wild type (UB5875) and ndc80-urs1∆ (UB5473) strains. Cells were grown in nutrient rich medium to exponential phase. Samples were fixed and hybridized with the Q 670 probes (bind to the common region of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF, shown in green) and the CF 590 probes (bind to the unique region of NDC80luti, shown in magenta) as in Figure 2C. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 5 µm. (E) Quantification of (D), graphed as the relative frequency histograms of cells with a given number of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF transcripts per cell, using data pooled from three independent experiments. The dashed line indicates the median number of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF transcripts per cell. A total number of 490 cells were analyzed for wild type and 427 for ndc80-urs1∆. Two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was performed for NDC80ORF and NDC80luti, respectively, comparing wild type with ndc80-urs1∆ in vegetative growth. (F) Ndt80-3V5 chromatin immunoprecipitation in untagged (UB7997), NDT80-3V5 (UB7999), and NDT80-3V5 ndc80-mse strains (UB7496). After 5 hr in SPO, NDT80 expression was induced with β-estradiol. One hour after Ndt80 induction, cells were fixed with formaldehyde and chromatin extracts were prepared. The recovered DNA fragments were quantified by qPCR using two primer pairs: one specific for the NDC80ORF promoter (pNDC80ORF) and one specific to the NDC80 coding region (NDC80 ORF). Enrichment at these loci was normalized to the signal from the NUF2 promoter, to which Ndt80 does not bind. The mean fold enrichment over the NUF2 promoter from three independent experiments, as well as the standard error of the mean, is displayed. (G) Representative smFISH images for NDC80luti and NDC80ORF during meiotic prophase in wild type (UB6190) and ndc80-urs1∆ (UB6075) strains. Samples were taken 2 hr after IME1 and IME4 induction in a synchronous meiosis experiment and processed as in Figure 2C. Scale bar: 5 µm. Note: the image for wild type is the same as the one shown in Figure 4B. (H) Quantification of (G), graphed as relative frequency histograms as in (E). A total number of 611 cells were analyzed for wild type and 668 for ndc80-urs1∆. Two-tailed Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was performed for NDC80ORF and NDC80luti, respectively, comparing wild type with ndc80-urs1∆ during meiotic prophase. Note: the histograms for the wild type cells are the same as those shown in Figure 4C. (I) NDC80ORF, NDC80luti, and Ndc80 levels during synchronous meiosis (as described in Figure 2B) in wild type cells (UB6190) and ndc80-urs1∆ cells (UB6075). (J) NDC80ORF, NDC80luti, and Ndc80 level during meiosis in wild type (UB4074) and ndc80-mse (UB3392) strains. Both strains harbor the pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER system. Cells were transferred to SPO at 0 hr and released from pachytene arrest at 6 hr by addition of β-estradiol.

Ime1 does not directly bind to DNA, but functions as a co-activator for Ume6 (Washburn and Esposito, 2001). In the absence of Ime1, Ume6 represses early meiotic genes in mitosis by binding to a consensus site called the upstream repressive sequence (URS1) in the promoters of these genes. Upon meiotic entry and subsequent interaction with Ime1, the Ume6-Ime1 complex activates the transcription of these early meiotic genes (Bowdish et al., 1995; Park et al., 1992). Given the close relationship between Ime1 and Ume6, we inspected the 5’ intergenic region of NDC80 and identified a consensus site for Ume6 583 bp upstream of the Ndc80 translation start site (Figure 6B and Figure 4—figure supplement 1), within the NDC80luti promoter. ChIP analysis revealed that Ume6 binding was enriched over the predicted URS1 site in mitosis and early meiosis (Figure 6C and Figure 6—figure supplement 2), whereas Ume6 binding was undetectable within the NDC80ORF promoter (Figure 6C and Figure 6—figure supplement 2). Deletion of the URS1 site (ndc80-urs1∆) completely abolished Ume6 binding to the NDC80luti promoter (Figure 6C), but did not affect another Ime1-Ume6 target gene IME2 (Figure 6—figure supplement 3). Consistent with the role of Ume6 as a transcriptional repressor in mitosis, deletion of the URS1 site resulted in leaky expression of NDC80luti during vegetative growth (Figure 6D and E, p<0.0001) and reduced expression of NDC80ORF (Figure 6E, p=0.0057). Abolishing Ume6 binding eliminated strong induction of NDC80luti in meiosis (Figure 6G and H, p<0.0001), causing moderately increased levels of NDC80ORF transcript by northern blot and Ndc80 protein in meiotic prophase (Figure 6I). We did not detect significant increase in NDC80ORF in the urs1∆ cells by smFISH (Figure 6H), likely due to technical reasons (See Materials and Methods). We conclude that similar to early meiotic genes, Ime1 and Ume6 directly regulate the transcription of NDC80luti.

The second key meiotic transcription factor, Ndt80, is required for meiotic chromosome segregation and spore formation (Chu and Herskowitz, 1998; Xu et al., 1995). Expression of NDT80 occurs shortly before the reappearance of NDC80ORF transcript. Within the budding yeast lineage, an Ndt80 consensus site, called the mid-sporulation element (MSE), was identified at 184 bp upstream of the Ndc80 translation start site (Figure 6B and Figure 4—figure supplement 1), within the NDC80ORF promoter. One hour after Ndt80 expression was induced in the pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER system, Ndt80 binding was enriched over the predicted MSE by ChIP analysis; moreover, mutations in the MSE (ndc80-mse) led to a complete loss of Ndt80 enrichment (Figure 6F), but did not affect another Ndt80 target gene MAM1 (Figure 6—figure supplement 4). Furthermore, the defect in Ndt80 binding to the NDC80ORF promoter reduced both NDC80ORF transcript and Ndc80 protein levels during the meiotic divisions (Figure 6J). These results demonstrate that Ndt80 directly induces NDC80ORF expression after meiotic prophase, and this timely induction of NDC80ORF elevates the levels of Ndc80 protein prior to the meiotic divisions.

Temporal regulation of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF expression is essential for the proper timing of kinetochore function

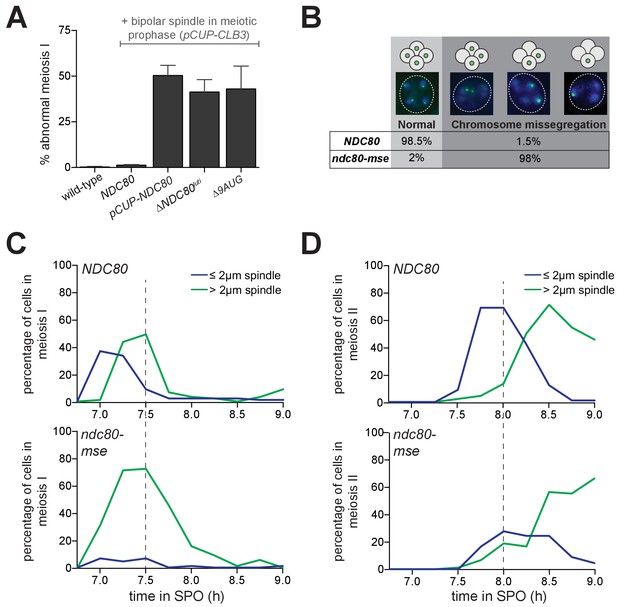

Since Ndc80 appears to be the limiting subunit of the kinetochore, we posited that the regulated expression of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF serves to inactivate and reactivate kinetochores, respectively, through modulating Ndc80 protein levels. In budding yeast, kinetochores are inactive in meiotic prophase (Miller et al., 2012, and Figure 1D), but they can be activated upon Ndc80 overexpression (Miller et al., 2012, and Figure 1D). We asked whether functional kinetochores could also be generated in meiotic prophase if cells failed to express NDC80luti (∆NDC80luti) or expressed a version of NDC80luti that could translate Ndc80 protein (∆9AUG). Both conditions caused an increase in Ndc80 levels in meiotic prophase (Figures 3 and 4A). Using the same assay described in Figure 1D, we observed that over 50% of the ∆NDC80luti or ∆9AUG cells displayed abnormal chromosome segregation in meiosis I (Figure 7A), suggesting premature kinetochore activity in meiotic prophase. The extent of this phenotype was indistinguishable from that when Ndc80 was overexpressed in meiotic prophase (pCUP-NDC80) (Figure 7A). Therefore, repression of NDC80ORF by NDC80luti transcription is crucial to inhibit untimely kinetochore function during meiotic prophase.

Temporal regulation of Ndc80 level by NDC80luti and NDC80ORF in meiosis is required for proper meiotic chromosome segregation.

(A) Sister chromatid segregation in wild type (UB2942), pCUP-CLB3 (UB877), pCUP-CLB3 pCUP-NDC80 (UB880), pCUP-CLB3 ∆NDC80luti (UB2940), and pCUP-CLB3 ∆9AUG (UB2936) cells. Cells were induced to sporulate by transferring to SPO, and 6 hr later, expression of the cyclin Clb3 was induced by addition of CuSO4. Immediately after induction, cells were released from pachytene by addition of β-estradiol. Samples were taken 1 hr 45 min after the release. Premature segregation of sister chromatids in meiosis I (abnormal meiosis I) was detected as two separated GFP dots in binucleates, one in each nucleus. The average fraction of binucleates that displayed sister segregation in meiosis I from three independent experiments, as well as the standard error of the mean, was graphed. 100 cells were counted per strain, per experiment. (B) Chromosome segregation accuracy in wild type (UB5876) and ndc80-mse (UB5437) strains was determined by counting homozygous CENV-GFP dots in tetranucleates. Samples were taken 7.5 hr after transfer to SPO when most cells had completed meiosis in an asynchronous system. The fraction of tetranucleates that displayed normal segregation (one GFP dot in each nucleus), or missegregation (multiple or zero GFP dots in any of the four nuclei) was quantified. The average fraction of normal segregation or missegregation from two independent experiments is shown. Over 100 cells were counted per strain, per experiment. (C–D) Percentage of wild type (UB4074) and ndc80-mse (UB3392) cells with meiosis I spindles (shown in C) or meiosis II spindles (shown in D) that were longer than 2 μm, as well as the percentage of cells with spindles that were shorter than 2 μm. Both strains harbor the pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER system. After 6 hr in SPO, the cells were released from pachytene by addition of β-estradiol, and samples were taken every 15 min after the release. Over 100 cells per time point were quantified, and the results of one representative repeat from two independent experiments are shown.

Functional kinetochores must be present after meiotic prophase to faithfully execute chromosome segregation during the two meiotic divisions. Since Ndc80 protein levels become nearly undetectable during prophase (Figure 1C), Ndc80 must be resynthesized to restore the ability of kinetochores to interact with microtubules upon exit from prophase. This resynthesis relies on the transcription factor Ndt80 to induce transcription of NDC80ORF (Figure 6F and J). To test the significance of Ndt80-dependent induction of NDC80ORF in meiosis, we monitored the segregation pattern of chromosome V in cells with a mutated Ndt80 binding site in the NDC80ORF promoter (ndc80-mse). Only 1% of wild type cells missegregated chromosome V, whereas 98% of the ndc80-mse cells failed to properly segregate this chromosome (Figure 7B), suggesting that kinetochores are not functional in ndc80-mse cells. In support of this conclusion, in ndc80-mse cells, elongated bipolar spindles (over 2 μm) appeared earlier and persisted longer than in wild type cells (Figure 7C), a phenomenon consistent with defective microtubule-kinetochore attachments (Wigge et al., 1998; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001). Additionally, the abundance of short meiosis II spindles (less than 2 µm) was reduced in the ndc80-mse cells (Figure 7D), and at the end of meiosis, more than four nuclei were often observed (representative images shown in Figure 7B). The ndc80-mse mutation also severely affected the sporulation efficiency (Figure 7—figure supplement 1). All of these results demonstrate that Ndt80-dependent induction of NDC80ORF is essential for re-establishing kinetochore function to mediate meiotic chromosome segregation.

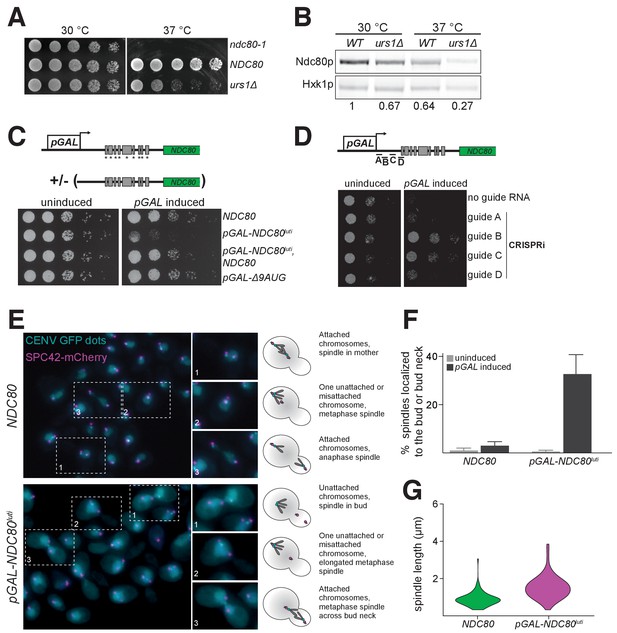

Unlike NDC80ORF transcript, NDC80luti is absent in vegetative growth due to repression by Ume6 (Figure 6D and E). We hypothesized that NDC80luti is repressed during the mitotic cell cycle because its expression could inactivate kinetochore function (Figure 5C and D). Indeed, when the Ume6 repressor-binding site within the NDC80luti promoter was deleted (urs1∆), these cells grew similar to wild type cells at 30°C, but they had a severe growth defect at 37°C due to reduced Ndc80 levels (Figure 8A and B). Thus, the repression of NDC80luti by Ume6 is critical for the fitness of mitotically dividing cells.

Misexpression of NDC80luti outside of meiosis causes severe growth defects due to kinetochore dysfunction.

(A) Growth phenotype of ndc80-urs1∆ cells at 30°C and 37°C. Temperature-sensitive ndc80-1 (UB494), wild type (UB3262), and urs1∆ (UB4212) cells were serially diluted and grown on nutrient rich medium (YPD) plates at 30°C or 37°C for 2 days. (B) Ndc80 level in wild type (UB3262) and urs1∆ (UB4212) cells grown at 30°C or 37°C. For each condition, equal OD600 of cells were taken, and Ndc80 was visualized by anti-V5 immunoblot. Hxk1, loading control. WT, wild type. The number under each lane is the ratio of the relative Ndc80 levels (normalized to Hxk1 levels) compared with that of wild type at 30°C. The results of one representative repeat from two independent experiments are shown. (C) Growth phenotype of haploid control (UB1240), pGAL-NDC80luti (UB1217), pGAL-NDC80luti with a second copy of NDC80 at the LEU2 locus (UB8001), and pGAL-∆9AUG (UB1323). Cells were serially diluted and grown on YEP-raffinose/galactose (YEP-RG) plates (uninduced) or YEP-RG plates supplemented with β-estradiol (pGAL induced) at 30°C for 2 days. (D) Growth phenotype of the pGAL-NDC80luti cells carrying a pGAL-inducible dCas9-Mxi1 and a vector for one of the following guide RNAs: gRNA A (UB6297), gRNA B (UB6299), gRNA C (UB6301), or gRNA D (UB6302). The control strain (UB6295) carries an empty vector. Cells were serially diluted and grown on SC –leu raffinose + galactose plates (uninduced) or SC –leu raffinose + galactose plates supplemented with β-estradiol (pGAL induced) at 30°C for 2 days. (E), (F), and (G) Phenotypic characterization of cells expressing pGAL-NDC80luti. Both the control (UB8682) and pGAL-NDC80luti (UB8684) cells harbor homozygous CENV-GFP dots and Spc42-mCherry (spindle pole body marker). The strains were grown overnight in YEP-RG, and samples were collected at 0 hr and 6 hr after pGAL induction by β-estradiol. (E) Representative images of wild type cells and the cells expressing NDC80luti after 6 hr of pGAL induction. Enlarged images of the boxed regions are shown in the middle. To the right are schematics of the microtubule-kinetochore attachment status in each class of phenotype observed. (F) Quantification of the spindle localization data shown in (E). Among the cells with separated spindle poles, the percentage of cells that had a spindle shorter than 2 µm and were abnormally localized (i.e. across the bud neck or entirely within the bud) is displayed. 100 cells were counted per strain, for each condition. The average percentage and the standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. (G) Quantification of the spindle length in cells with at least one chromosome V not attached to a spindle pole body. Data from (E), specifically in cells with either both CENV-GFP dots associated with a single spindle pole or both CENV-GFP dots completely dissociated from either spindle pole. This allows analysis of populations of cells that are either in Sphase/early mitosis (after SPB duplication, but before chromosome alignment) or are unable to properly attach their chromosomes. A representative replicate out of three independent experiments was graphed as a violin plot. 100 cells were analyzed per strain, per replicate.

When NDC80luti was strongly induced in vegetative growth using the inducible GAL1-10 promoter, these cells had a severe growth defect (Figure 8C). This defect was rescued by a second copy of NDC80 at an ectopic locus, consistent with the notion that NDC80luti-mediated repression of NDC80ORF occurs in cis (Figure 8C and Figure 4D). Cell death was also rescued by silencing the pGAL-induced NDC80luti expression using CRISPRi (Qi et al., 2013) (Figure 8D), presumably due to the activation of the NDC80ORF promoter in the absence of NDC80luti transcription. Induction of the uORF-free NDC80luti (∆9AUG) caused no appreciable growth defect (Figure 8C), consistent with the observation that the ∆9AUG cells could express Ndc80 protein (Figure 3).

The inducible nature of the GAL1-10 promoter allowed us to directly test whether the growth defect associated with the mitotic NDC80luti expression arose from defects in kinetochore function. We performed fluorescence microscopy to track spindle length (Spc42-mCherry) and chromosome segregation (CENV-GFP dots). Cells expressing NDC80luti displayed a range of kinetochore-microtubule attachment defects (Figure 8E, bottom panel). In cells with separated spindle pole bodies, ~30% of the cells expressing NDC80luti had metaphase spindles (≤2 μm) improperly localized to either the bud or the bud neck, whereas only 3% of the wild type cells displayed this phenotype (Figure 8F). Furthermore, in cells expressing NDC80luti, an abnormal distribution of spindle length was observed, characteristic of a metaphase arrest (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). Spindle elongation was also observed prior to chromosome capture, suggesting improper kinetochore function (Figure 8G). Collectively, these analyses revealed that the strict temporal regulation of NDC80luti and NDC80ORF transcription in both mitosis and meiosis is essential to ensure the proper timing of kinetochore function and high fidelity chromosome segregation.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified an integrated regulatory circuit that controls the inactivation and subsequent reactivation of the meiotic kinetochore (Figure 9). This circuit controls the synthesis of a limiting kinetochore subunit, Ndc80, and relies on the regulated expression of two distinct NDC80 mRNAs. A meiosis-specific switch in promoter usage induces the expression of a 5’ extended transcript isoform, NDC80luti, which itself cannot produce Ndc80 protein. Rather, its function is purely regulatory. Transcription of this alternate isoform leads to repression of the protein-translating NDC80ORF isoform in cis. This results in inhibition of Ndc80 protein synthesis and ultimately the inactivation of kinetochore function in meiotic prophase. Reactivation of the kinetochore is achieved by the transcription of NDC80ORF upon exiting meiotic prophase. Temporally coordinated by two master transcription factors, the timely expression of these two mRNA isoforms is essential for kinetochore function, accurate chromosome segregation, and gamete viability. Altogether, our study describes a new gene regulatory mechanism and provides insight into its biological purpose.

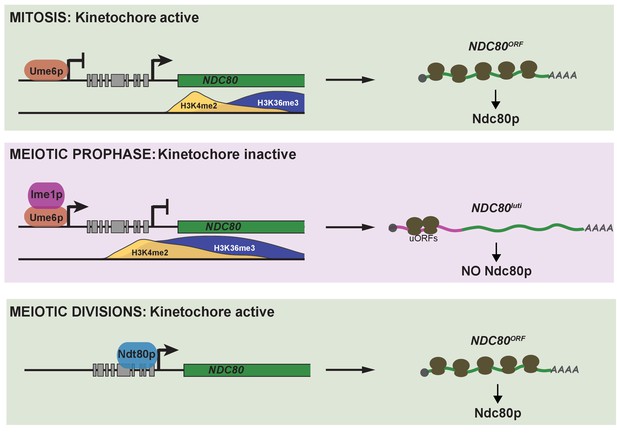

Model of NDC80 gene regulation in budding yeast.

During vegetative growth, a stage in which kinetochores are active, a short NDC80 mRNA isoform NDC80ORF is expressed, and the 5’ extended isoform NDC80luti is repressed by Ume6. Translation of NDC80ORF results in Ndc80 protein synthesis (top panel). At meiotic entry, the master transcription factor Ime1 induces expression of NDC80luti. Transcription from this distal NDC80luti promoter silences the proximal NDC80ORF promoter through a mechanism that increases H3K4me2 and H3K36me3 marks over the NDC80ORF promoter (See the accompanying paper Chia et al., for details). NDC80luti does not support Ndc80 synthesis due to translation of the uORFs. The overall synthesis of Ndc80 is repressed in meiotic prophase, and the kinetochores are inactive (middle panel). As cells enter the meiotic divisions, the transcription factor Ndt80 induces NDC80ORF re-expression, allowing for Ndc80 re-synthesis and formation of active kinetochores (bottom panel).

A limiting subunit controls kinetochore function in meiosis

In meiosis, kinetochore function is transiently inactivated to facilitate accurate chromosome segregation (Miller et al., 2013). This transient inactivation is achieved by the removal of the outer kinetochore from chromosomes and has been described in organisms ranging from yeast to mice (Asakawa et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2011). In budding yeast, we found that outer kinetochore removal is mediated by limiting the abundance of a single subunit, Ndc80. Ndc80 is the only member of its complex whose protein abundance is essentially absent in meiotic prophase (Meyer et al., 2015 and Figure 1C). Furthermore, prophase overexpression of NDC80, but none of the other Ndc80 complex subunits, promotes premature spindle attachments and causes meiotic chromosome segregation errors (Figure 1D). Thus, in the case of the meiotic kinetochore, the cell regulates the activity of a multi-protein complex by limiting the availability of a single subunit.

The control of protein complex activity through the limitation of a key subunit is a more general principle. A genome-wide study that analyzed the composition of protein complexes during the cell cycle revealed that in budding yeast, most protein complexes have both constitutively and periodically expressed subunits (de Lichtenberg et al., 2005). It is proposed that due to the periodically expressed subunits, these protein complexes assemble "just-in-time" to restrict their function to specific cell cycle stages (de Lichtenberg et al., 2005). The luti-mRNA-dependent regulatory circuit described here may more broadly address how regulated subunits are provided "just-in-time" and, importantly, at no other time.

NDC80luti is an mRNA that does not produce protein

A key aspect of the work presented here is the surprising finding that an mRNA can serve a purely regulatory function. Indeed, NDC80luti is a bona fide mRNA. It is poly-adenylated, is engaged by the ribosome and, most importantly, when the uORF start codons are ablated, Ndc80 protein is translated from this extended mRNA isoform (Brar et al., 2012 and Figure 3). Moreover, NDC80luti is likely a RNA Polymerase II transcript because its promoter is occupied by the pre-initiation complex member Sua7 (TFIIB) and because Pol II-associated chromatin marks are detected downstream of the NDC80luti promoter when this transcript is made (Chia et al., accompanying manuscript). NDC80luti cannot be decoded by the ribosome due to the presence of AUG-uORFs contained in its extended 5’leader. By competitively engaging the ribosome, these uORFs prevent translation of Ndc80 protein. The polypeptides that the uORFs encode are unlikely to play a role in the repression of kinetochore function as the uORFs can be minimized to 2-codon units while maintaining NDC80luti-based repression (Figure 3). Interestingly, upstream AUG codons are also present in the putative NDC80luti mRNAs predicted from the other fungal species. Three regions were enriched for the presence of such AUGs (Figure 9—figure supplements 1 and 2), but the sequences and the length of these putative uORFs did not seem to be conserved (Supplementary file 1G). This observation is consistent with the idea that the act of uORF translation, rather than the identity of the uORF peptides, serves as a conserved feature in evolution.

The repressive nature of the uORFs contained in NDC80luti mirrors those found in the uORF-containing prototype transcript, GCN4 (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986). However, in the case of GCN4, changes in nutrient availability can relieve the uORF-mediated translational repression, whereas for NDC80luti, the uORF-mediated repression appears to be constitutive. In both cases, GCN4 and NDC80 can exist in on and off states. For GCN4, this switch is manifested in the two translational states of the same mRNA molecule. For NDC80, the switch is manifested instead by two distinct transcripts, one, which results in protein synthesis and one, which represses protein synthesis. It is important to note that for other potential luti-mRNAs, the precise mechanism of translational repression may not be conserved and could instead involve other means such as RNA hairpins or binding sites for translational repressors.

The function of NDC80luti mRNA is purely regulatory

Why do meiotic cells express an mRNA that does not encode any functional polypeptides? We propose that the biological purpose of NDC80luti is to shut down Ndc80 protein synthesis by repressing NDC80ORF in cis, thereby inactivating kinetochore function during meiotic prophase. Multiple lines of evidence support this model. First, disruption of NDC80luti expression in meiosis results in elevated levels of NDC80ORF and Ndc80 protein in meiotic prophase, leading to premature kinetochore activation (this study and Chia et al., accompanying manuscript). Second, induction of NDC80luti transcription in cis is sufficient to repress NDC80ORF and inactivate kinetochore function in mitotic cells (this study). Third, transcription of NDC80luti introduces repressive chromatin marks at the NDC80ORF promoter that are necessary for the downregulation of NDC80ORF and Ndc80 protein (Chia et al., accompanying manuscript). Altogether, these findings strongly suggest that the primary function of the NDC80luti mRNA is to turn off the NDC80 gene.

It is important to note that our study only addresses the mechanism of how Ndc80 protein synthesis is repressed in meiotic prophase. Indeed, efficient and timely reduction of Ndc80 protein levels may require regulated proteolytic mechanisms not yet elucidated. Further studies are necessary to determine if proteolysis plays a role in the rapid removal of the outer kinetochore in meiotic prophase and if so, by what means this proteolysis is achieved.

Transcription factor-driven gene repression by luti-mRNA: an evolutionary perspective

Why do budding yeast cells use this seemingly complex mechanism, which relies on the transcription of an undecoded mRNA isoform, to repress a kinetochore gene during meiosis? We would argue from an evolutionary point of view that this solution could be both economical and highly flexible. First, the meiotic cell is co-opting two existing transcription factors, Ime1 and Ndt80, for roles in activating and repressing gene expression, obviating the need to evolve novel trans-acting factors. This mechanism also ensures temporal coordination of gene activation and inactivation using the same transcription factor. In the case of NDC80, the luti-mRNA rides the Ime1 wave of gene expression to shutoff kinetochore function while the protein-coding mRNA rides the subsequent Ndt80 wave to reactivate the kinetochore for the division phases. While transcription factors have previously been implicated in the repression of downstream promoters (Bird et al., 2006; Martens et al., 2004; Shearwin et al., 2005; van Werven et al., 2012), our study is the first clear demonstration that it is the choice of promoter and the identity of the resulting mRNA isoform that governs whether a gene is turned on or turned off by a given transcription factor.

This mode of gene repression relies on two sets of cis-regulatory sequences, which are evolutionarily flexible (Carroll, 2008; Stern and Orgogozo, 2008; Wittkopp and Kalay, 2011). The first cis-acting sequence is the distal transcription factor-binding site, which induces transcription of NDC80luti, and, in concert with co-transcriptional chromatin modifications, silences the downstream canonical promoter activity. The second cis-acting sequence is the AUG-uORFs within the extended 5’ leader of the luti-mRNA, which prevents downstream ORF translation. Inherent to a mechanism that is so heavily reliant on cis-regulatory elements is the notion that minor changes in the DNA sequence can impact gene expression at a multitude of levels, thus tuning gene output. This tuning can be manifested at the level of nucleosome spacing, strength of transcription factor binding and translational regulation. Therefore, the cell has a vast evolutionary space, which can be explored through small changes in DNA sequence.

Pervasiveness of luti-mRNA biology in yeast meiosis and beyond

The defining sequence features of the NDC80 luti-mRNA are a 5’-extended mRNA leader coupled with repressive uORFs contained in this extended leader. Analysis of the mRNA-seq and ribosome profiling datasets of meiotic yeast revealed hundreds of transcripts with potential luti-like signatures (Brar et al., 2012). In support of this idea, two other genes, ORC1 and BOI1, have been shown to express meiosis-specific transcript isoforms with uORF-containing leader extensions (Xie et al., 2016 and Liu et al., 2015). Rather than dissecting each candidate luti-mRNA on a case by case basis, future studies that integrate additional genome-wide datasets to measure stage-specific transcription factor binding sites, transcription-coupled chromatin modification states, mRNA translation status with isoform specificity and protein abundance would result in a high-confidence map of luti-mRNAs and aid in the dissection of their cellular functions.

Beyond budding yeast meiosis, can the regulatory circuit described in our study be present in other developmental programs and in other organisms? We would argue so, because various organisms also possess the three principles of this module, namely, alternative promoter usage, transcription-coupled repression, and uORF-mediated translational repression. Alternative promoter usage is widespread in development and among different cell types. For example, in the fruit fly, more than 40% of developmentally expressed genes have at least two promoters with distinct regulatory programs (Batut et al., 2013). Half of human genes have more than one promoter, resulting in the expression of mRNA isoforms with 5’ heterogeneity (Kimura et al., 2006). Furthermore, transcription-based interference mechanisms, as well as transcription-coupled histone modifications, have been described in a variety of organisms (Corbin and Maniatis, 1989; Eissenberg and Shilatifard, 2010; Shearwin et al., 2005; Wagner and Carpenter, 2012). Finally, recent studies have shown that uORF translation is much more widespread than traditionally believed and acts in a regulatory manner (Calvo et al., 2009; Chew et al., 2016; Johnstone et al., 2016). Therefore, we envision that the regulatory circuit described here can be used as a roadmap in future studies to uncover transcription-coupled gene repression during cell fate transitions across multiple species.

Interpreting genome-wide data in the context of luti-mRNA biology

A key implication of this model of gene regulation is a blurring of the line between "coding" and "non-coding" RNAs. Seminal work has uncovered multiple classes of non-coding RNAs that play regulatory functions in the cell, such as long non-coding RNAs, microRNAs, small interfering RNAs, and piwiRNAs (Ambros, 2001; Batista and Chang, 2013; Cech and Steitz, 2014; Guttman et al., 2009). Our study demonstrates that mRNAs, which are deemed protein coding units, can themselves be direct regulators of gene expression by at least two simultaneous means: they can induce transcription-coupled silencing of a downstream promoter, and features in their 5’ leaders, such as the presence of uORFs or secondary structures, could directly impact translation efficiency in a positive or negative manner (Arribere and Gilbert, 2013; Brar et al., 2012; Rojas-Duran and Gilbert, 2012). Notably, multiple studies have reported poor correlation between mRNA and protein abundance (Maier et al., 2009). For those mRNAs that anti-correlate with their protein levels, this apparent contradiction might be due to a luti-mRNA being misattributed as a canonical protein-coding transcript. Our study could dramatically transform the way we understand the function of alternate mRNA isoforms and aid in the proper biological interpretation of genome-wide transcription studies.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

Request a detailed protocolAll the strains used in this study are described in Supplementary file 1A and are derivatives of SK1. The pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER and the pCUP-IME1 pCUP-IME4 synchronization systems have been described previously (Benjamin et al., 2003; Berchowitz et al., 2013). The centromeric TetR/TetO GFP dot assay is described in (Michaelis et al., 1997). The ndc80-1 temperature-sensitive mutant was first described in (Wigge et al., 1998), the Zip1::GFP (700) described in (Scherthan et al., 2007), and pCUP-NDC80 pCUP-CLB3 described in (Miller et al., 2012). NDC80-3V5, NUF2-3V5, SPC24-3V5, SPC25-3V5, pCUP-NUF2, pCUP-SPC24, pCUP-SPC25, pGAL-NDC80luti, pGAL-∆9AUG, ndc80∆, nuf2∆, (∆−600 to −300)-NDC80, and (∆−600 to −400)-NDC80 were generated at the endogenous gene loci using PCR-based methods (Longtine et al., 1998). The V5 plasmid is kind gift from Vincent Guacci. Primer sequences used for strain construction can be found in Supplementary file 1B. Single integration plasmids carrying either NDC80 or NUF2 were constructed by Gibson Assembly (Gibson et al., 2009), and were digested with PmeI to integrate at the LEU2 locus. For NDC80, the LEU2 integration plasmid included the SK1 genomic sequence spanning from 1000 bp upstream to 357 bp downstream of the NDC80 coding region; and for NUF2, spanning from 1000 bp upstream to 473 bp downstream of the NUF2 coding region. Both constructs included a C-terminal fusion of the 3V5 epitope to NDC80 and NUF2, and both completely rescued the full deletion of NDC80 or NUF2, respectively. Deletions (ndc80-urs1∆ and (∆−600 to −479)-NDC80) and point mutations (ndc80-mse) were generated from the NDC80 LEU2 single integration plasmid using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, NEB, Ipswitch, MA). The entire URS1 site and the "A" right upstream of the site were deleted in the ndc80-urs1Δ strain. The ndc80-mse construct has two C to A mutations, marked using black diamonds in Figure 6B. The ∆6AUG, ∆9AUG, mini uORF, NDC80luti-Ter, and NDC80luti-NUF2 constructs were generated by Gibson assembly (Gibson et al., 2009) using the NDC80 and NUF2 LEU2 integration plasmids, as well as gBlocks gene fragments (IDT, Redwood City, CA) for the ∆9AUG and mini uORF constructs. SNR52 promoter-controlled guide RNAs targeting NDC80luti (A-D) were cloned into a 2-micron plasmid carrying a LEU2 selectable marker (pRS425 backbone). See Supplementary file 1C for the full list of the integration and 2-micron plasmids.

pCUP-IME1 pCUP-IME4 synchronous sporulation

Request a detailed protocolSynchronously sporulating cell cultures were prepared as in (Berchowitz et al., 2013). In short, the endogenous promoters of IME1 and IME4 were replaced with the inducible CUP1 promoter. Diploid cells were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and supplemented with 22.4 mg/L uracil and 80 mg/L tryptophan) for 20–24 hr at room temperature. For optimal aeration, the total volume of the flask exceeded the volume of the medium by 10 fold. Subsequently, cells were transferred to BYTA (1% yeast extract, 2% bacto tryptone, 1% potassium acetate, 50 mM potassium phthalate) and grown for another 16–18 hr at 30°C. The cells were then pelleted, washed with sterile milliQ water, and resuspended at 1.85 OD600 in sporulation (SPO) media (0.5% (w/v) potassium acetate [pH 7], 0.02% (w/v) raffinose) at 30°C. To initiate synchronous sporulation, expression of IME1 and IME4 was induced 2 hr after cells were transferred to SPO by adding copper (II) sulphate to a final concentration of 50 µM.

pGAL-NDT80 synchronous meiotic divisions

Request a detailed protocolThe pGAL-NDT80 GAL4-ER system was used to generate populations of cells synchronously undergoing the meiotic divisions (Carlile and Amon, 2008). Cells were prepared for meiosis as in the pCUP-IME1 pCUP-IME4 protocol, and resuspended at 1.85 OD600 in SPO. The flasks were placed at 30°C for 5–8 hr to block cells in meiotic prophase (See figure legend for the specific arrest duration for each experiment). To release cells from pachytene, NDT80 expression was induced with 1 μM β-estradiol. Subsequently, cells progressed through meiosis synchronously.

Alpha-factor arrest-release mitotic time course

Request a detailed protocolMATa cells were first grown to an OD600 of 1–2 at 30°C in YPD, diluted back to OD600 0.005 in YEP-RG (2% raffinose and 2% galactose in YEP supplemented with 22.4 mg/L uracil and 80 mg/L tryptophan), and then grown at room temperature for 15–17 hr. Exponentially growing cells were diluted again to an OD600 of 0.19 in YEP-RG, and arrested in G1 with 4.15 μg/mL alpha-factor, and 1.5 hr later, an additional 2.05 μg/mL of alpha-factor was added to the cells. After 2 hr in alpha-factor, 1 μM β-estradiol was added to cultures to induce pGAL expression. One hour after the β-estradiol addition, cells were filtered, rinsed with YEP (10 times volume of the culture volume) to remove the alpha-factor, and placed into a receiving flask containing YEP-RG with 1 μM β-estradiol. Time points were taken before β-estradiol induction, before release, and every 15 min after release, for 3 hr.

Conservation analysis

Request a detailed protocolClustal analysis (Goujon et al., 2010; Sievers et al., 2011) was performed using the genomic sequences of S. bayanus, S. kudriavzevii, S. mikatae, S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus from Saccharomyces sensu stricto genus (Scannell et al., 2011), and imported into the Webpage of the Clustal Omega Multiple Sequence Alignment tool < http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/>.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Request a detailed protocolThe Ume6-3V5 chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously with the following modifications (van Werven et al., 2012). Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (1% v/v) for 15 min. Frozen cell pellets were disrupted 4 times (5 min each) using a Beadbeater (Mini-Beadbeater-96, Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Chromatin was sheared 5 × 30 s ON/30 s OFF with a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) to a fragment size of ~200 bp. Chromatin extracts were incubated with 20 μL of anti-V5 agarose beads (A7345, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 4°C. The Ndt80-3V5 chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously with the same modifications as used for Ume6-3V5 except for the sonication conditions (Strahl-Bolsinger et al., 1997). Chromatin was sheared 5 × 10 s ON/30 s OFF with a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) to a fragment size of ~500 bp. Reverse crosslinked input DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified with Absolute SYBR green (AB4163/A, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and quantified with a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher) using the primer pairs directed against the upstream region and the coding region of NDC80, the MAM1 promoter, and the IME2 promoter. We also measured the signals from the NUF2 promoter and HMR, regions that do not display significant binding for either of the transcription factors. The oligonucleotide sequences used are listed in Supplementary file 1D.

Fluorescence microscopy (CENV-GFP dots and Spc42-mCherry)

Request a detailed protocolCells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, washed once with potassium phosphate/sorbitol buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.5], 1.2 M sorbitol), and then permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 with 0.05 μg/mL DAPI in potassium phosphate/sorbitol buffer. Cells were imaged using a DeltaVision microscope with a 100x/1.40 oil-immersion objective (DeltaVision, GE Healthcare, Sunnyvale, CA) and filters: DAPI (EX390/18, EM435/48), GFP/FITC (EX475/28, EM525/48), and mCherry (EX575/25, EM625/45). Images were acquired using the softWoRx software (softWoRx, GE Healthcare).

Quantification of spindle length and CENV-GFP dots in mitosis

Request a detailed protocolFor Figure 8E–G and Figure 8—figure supplement 1, diploid cells were first grown to an OD600 of 1–2 at 30°C in YPD. They were then diluted to an OD600 of 0.002 in YEP-RG and grown at 30°C for 16 hr. Exponentially growing cells were diluted back to an OD600 of 0.2 in YEP-RG and induced to express NDC80luti with 1 μM β-estradiol. Samples were taken before induction and 6 hr after induction. Images were acquired as described in the fluorescence microscopy method section, and analysed using the FIJI image processing software (RRID:SCR_002285, Schindelin et al., 2012). First, maximum-intensity projection was performed. Second, projected spindle length (defined as the distance between Spc42-mCherry foci) was measured using the "measure" plugin. The distribution of the projected spindle length was graphed as violin plots using (BoxPLotR RRID:SCR_015629, Spitzer et al., 2014). Third, in cells with separated spindle poles, the status of the Spc42-mCherry association with CENV-GFP dots was categorized as 1) each Spc42-mCherry focus is associated with a CENV-GFP dot, 2) only one Spc42-mCherry focus is associated with CENV-GFP dots (either one or both of the GFP dots), or 3) neither Spc42-mCherry focus is associated with a CENV-GFP dot. After categorizing the localization of the CENV-GFP dots, the projected spindle length was measured for spindles in category 2 and 3, and the spindle length distributions were graphed as violin plots using (BoxPLotR RRID:SCR_015629, Spitzer et al., 2014). Finally, in cells with separated spindle poles, the location of the spindle was recorded as 1) in the mother, 2) across the bud neck, or 3) in the bud. The percentage of spindles that were both less than 2.0 μm and abnormally localized (across the bud neck or in the bud) was calculated. For each analysis, 100 cells were counted.

Indirect immunofluorescence